What would you say if we told you that one solution to fashion’s environmental impact grows underwater? Or that a group of shiny, slimy ribbons, otherwise known as algae, have the ability to help fashion pivot from environmental disaster to an industry that creates a genuine, positive impact?

For the most part, you’d probably call bullshit, or at least sound the greenwashing clickbait alarm. And while you’d partly be right (there is no one solution here, especially not without addressing the critical issue of overproduction first), there is research underway that backs these statements up.

If you’re at least marginally interested in sustainability, it’s likely that you’ve heard about the many benefits of algae, the group of simple aquatic plants that grow in oceans, rivers, lakes, and other bodies of water. It seems as though everyone is jumping on the algae bandwagon at the moment. As The New York Times recently observed, the plants have gone from centuries of near-global neglect to a worldwide hot commodity, leaped upon as an important source of food, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetic additives, and a promising source for developing biofuels and bioplastics. And for the last few years, a number of design innovators have been exploring its potential within the fashion industry, too.

Why? Because algae is a carbon-sucking powerhouse. According to researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Biology, brown algae is a “wonder plant” that has the power to counteract global warming. As loungewear brand Pangaia’s Chief Innovation Officer, Dr. Amanda Parker tells us: it’s “an incredible organism that grows abundantly and regeneratively in the ocean. It plays a vital role in capturing carbon for the planet, as the only organism which photosynthesizes in all of its cells (other plants photosynthesize only in their leaves) it provides at least 50 percent of the earth’s oxygen.”

In other words, algae remove carbon dioxide from the air at a huge rate and use it to grow. It’s also far less water and resource-intensive than conventional land materials like cotton, wool, and silk. We’re simplifying here, of course, but when the benefits are so monumental, it is curious that the fashion industry hasn’t started to embrace it en masse. But when we’re talking about multi-billion dollar industries, these types of change don’t happen overnight. As tends to be the case when exploring alternative solutions, it’s the small independent brands and creatives that are leading the way, asking the questions that cut to the core of the issue, and developing innovative solutions. (That we know of, Pangaia is one of the few big — yet still independent — fashion brands that currently actively incorporates algae into its collections).

“Some of the [production processes] haven’t changed for 100 years,” says Steve Tidball, who co-founded the menswear label Vollebak along with his twin brother Nick in 2015 following a career in advertising. “You have huge companies with vested interests in those processes not changing. People talk about change and then you get in on the inside [and see that] there really isn’t much. It’s just a lot of lip service. We found that really fascinating.”

While Vollebak is primarily a fashion brand, it’s actually more of a lab, constantly experimenting and playing with left-field concepts that have earned it a reputation for being a masterpiece manufacturer and a bit bonkers. “Everyone talks about [the fashion industry] as saturated,” Tidball continues, “But it’s also quite rigid. There are certain ways of putting clothes together. You can stitch them or bond them. That’s it. You get down to these incredibly simple things, and then it’s like, ‘Oh, and everyone does a catwalk. Let’s do a catwalk.’ I’m always quite amused when you come into a system and it’s so set in its ways that it doesn’t take a huge amount to disrupt it.”

Disruption is also what led Tessa Callaghan to launch the ocean-focused material innovation platform Keel Labs with co-founder Aleks Gosiewski. According to Callaghan, “The most creativity comes from the highest amount of restrictions.” After graduating from New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, both Callaghan and Gosiewski had high hopes for their future in fashion. We “went in thinking that as designers we would have choices to change the practices that we were using, but found that there was literally nothing that we could do. There were no materials that were available that actually provided solutions to the waste and pollution within the industry. So we began to think, ‘Why is that?’”

In response, they started making a list of the many negative side effects within the traditional supply chain, noting consequences like carbon emissions, microplastics, water usage, pesticides, and soil degradation. Their conclusion? “There’s no real land-based agriculture that is beneficial as it stands and widely available. So let’s look to a place that isn’t being used. Let’s look to the ocean. And what in that is readily available on a global scale, and also provides positive environmental impacts? Seaweed.”

From there, the fun began: working out how to spin harvested algae into yarn like some sort of wave-dwelling Rumpelstiltskin. Naturally, the process is not simple, but it is kind of like magic. Callaghan explains: “We create the recipes from these different raw materials the same way that a bakery uses flour; they’re not harvesting the wheat themselves. There’s this abundant harvesting and extraction industry around seaweeds and kelps, [and] we’re able to tap into that, [and] source those polymers. Then in-house we create proprietary chemistries that allow seaweed to be directly dropped into existing fiber manufacturing infrastructure. We take out all the toxic chemicals and just use water. Everything that goes into that system and everything that comes out of it is non-toxic, beneficial for the planet, and biocompatible.”

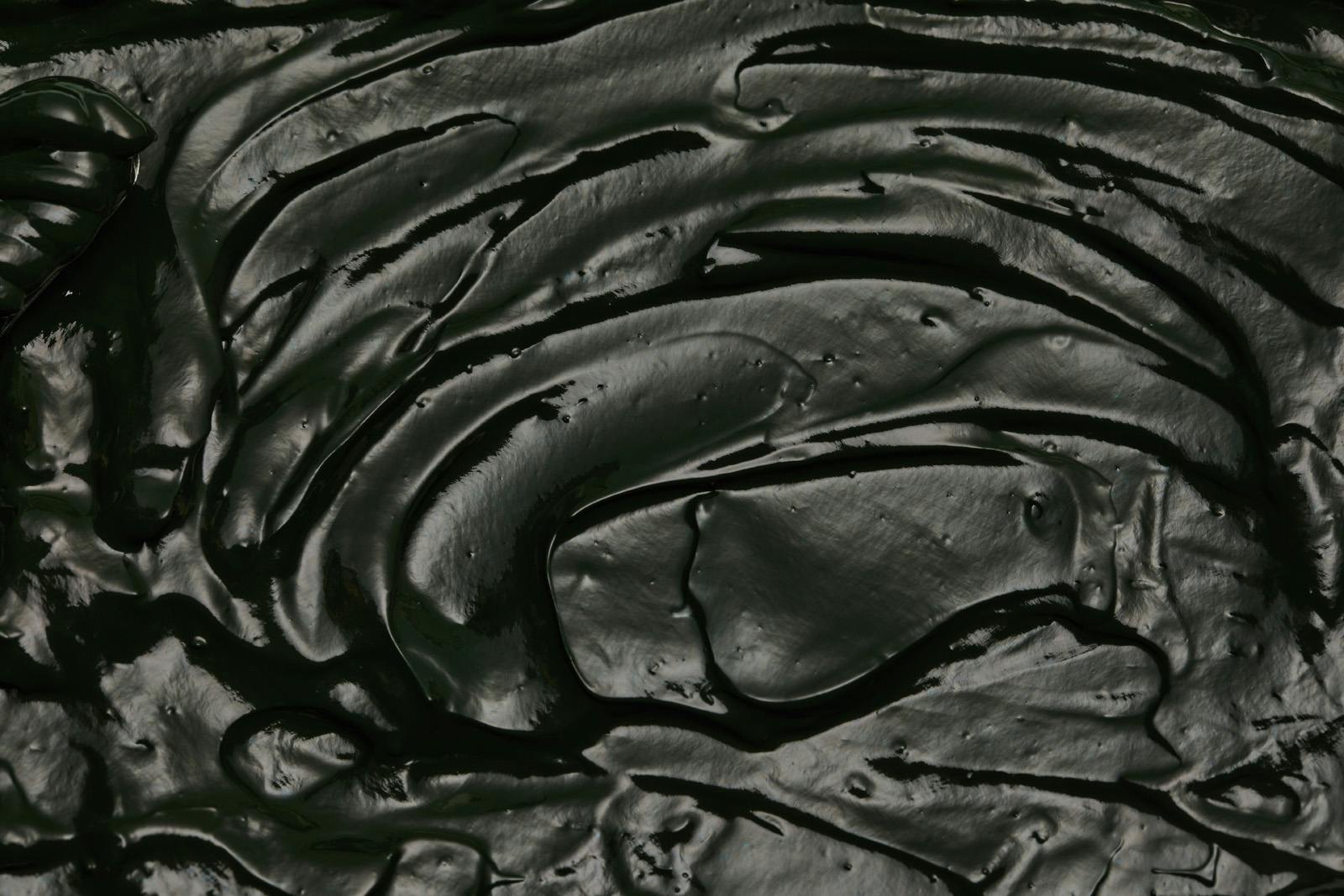

Creating solutions that are compatible with existing manufacturing infrastructure is a huge hurdle and, in terms of scaling such experiments, it’s the most restrictive, as Vollebak knows well. Last year, it released the “first ever” piece of clothing dyed with black algae. The success of the black algae dye is a huge milestone in sustainable fashion, though one that might fly under the radar as many of us don’t realize that clothing is dyed black — along with most other black objects like your phone case and the ink in your pen — with petroleum, with fossil fuels.

The black algae dye took five years of research and development with Living Ink, a biomaterials company that specializes in developing inks from algae. But, as Tidball explains, even once you’ve cracked it “you’ve still got to find people who are willing to put powdered algae into their printing machines that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. If they’re putting regular ink that’s been tested by all the big companies that they’ve used for the last 20 years, they’ll whack in anything you want. The minute you go, ‘I’ve got a bag of algae,’ you might as well tell them you’ve got a bag of drugs.”

The path to large-scale manufacturers embracing algae dye is probably a long one, but the potential impact could be seismic. “In relation to color,” Tidball continues, “algae effectively acts as a carbon lock. It uses the carbon dioxide to grow, and then the freezing method [that Living Ink has developed for the dye] locks in the carbon. That’s why algae are particularly effective in this area. It’s not just replacing something harmful, it’s then doing something interesting. If that’s being carried out at scale, that matters.”

But there’s no point in developing a carbon-capturing algae dye and then whacking it on polyester, which leads us back to Keel Labs who are currently developing their first seaweed-based yarn, Kelsun. According to Callaghan, the feedback for Kelsun so far has been great. The fibers “are really soft and have a really natural feel, look, and touch to them.” But it’s not yet available to buy commercially; they’re still in test and develop mode, working with a number of brands and designers so they’re sure the product they eventually bring to market hits all the right beats.

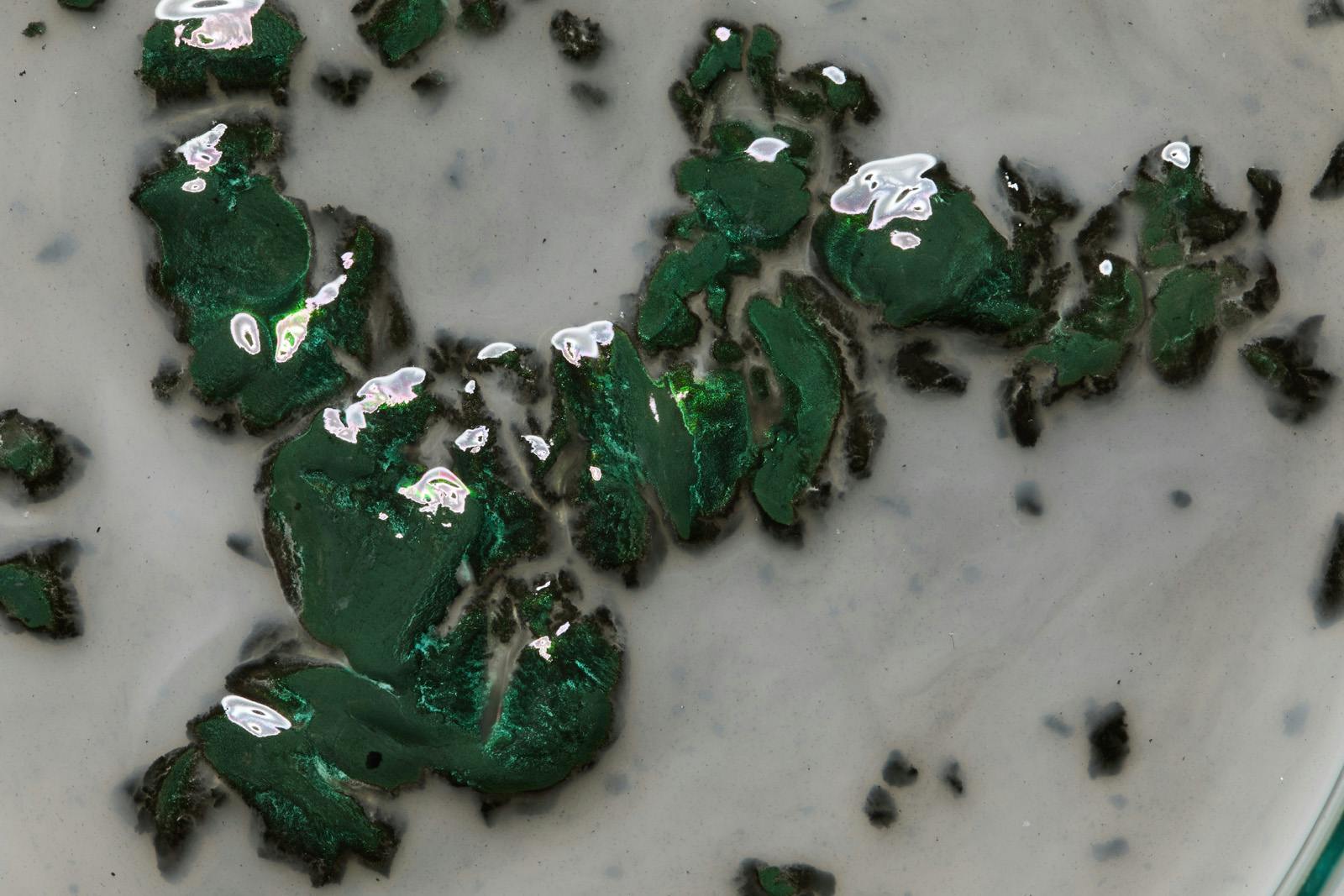

So far, brands that have already released algae collections — like Pangaia — have been blending it with other fibers. “Our current seaweed fiber is blended with organic cotton,” says Pangaia’s Dr. Parkes, explaining that the reason they do so is because algae “grows in a different structure than cotton fibers.” While cotton processing is “well understood [because it’s] been industrially produced for hundreds of years,” obviously seaweed has not. “Seaweed needs to be combined into a liquid slurry and extruded for use as a yarn. As with any new innovative material, research, and development into [these] processes are necessary to create expertise [which in turn leads to] superior production.”

Vollebak, Keel Labs, and Pangaia work with algae in different ways, yet they all share a vision of its potential for a better future. They’re also united in the message that developing such solutions requires an all-hands-on-deck approach — particularly, it needs the backing of big business to take it from a niche experiment to an industry standard.

“We are seeing corporations take initiative before they’re being forced (by impending regulations), which is critical,” says Callaghan, who notes that H&M is one of Keel Labs’ investors. “If you want to commit to your goals as a corporation or even as an individual, you need to acknowledge that support is required on all sides to make that happen. [Brands that put] their money where their mouth is to help themselves change, versus just saying that they have a goal and hoping that somebody shows up to fix it for them. It is a very different way of participating.”

But the challenge of helping the supply chain better itself does not just rest on algae’s shoulders. As the old adage goes, too much of anything is good for nothing, which is what climate correspondent Somini Sengupta was indicating to The New York Times, as noted above. As the globe increasingly turns to kelp to “Help tame some of the hazards of the modern age,” she writes, there’s a danger that we’ll cause unforeseen damage. We need to approach such solutions with care, with respect, and in tandem with a myriad of other alternative pathways.

Or, as Tidball put it: “I think the mistake would be looking at it as a single source of truth or a singular solution. It isn’t. It is one of many, many solutions. But” — and this is a fundamental but — “it is really, really promising.”