GEOLOGY

THE ORIGIN STORY

How glaciers, global warming, and one giant meteor helped create the Chesapeake.

long, long time ago. That’s when the Chesapeake

Bay was born. And the number changes, depending

on who you ask or how you look at it. Some

say it’s 10,000 years ago, when this estuary—a

body of water that blends rivers and oceans—first settled into its

modern state. Others claim that it’s even older, dating to when

the land first gave way to a wider and wider river valley—the predecessor

of our present Bay. And few could argue, too, that it goes

back further than that, to when the dinosaurs once reigned.

Whatever its birthday, the Bay’s formation is an epic and

extraordinary story that sets the tone for its current magnitude.

“We’re talking hundreds of millions of years,” says Richard Ortt,

acting director of the Maryland Geological Survey. “Are you ready

for a history lesson?”

ANCIENT OCEAN SHORELINE IN MARYLAND, CIRCA AT LEAST 12,000 YEARS AGO.—WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Before there was an Atlantic Ocean, what we now think of as

North America collided with North Africa as part of one colossal

supercontinent, known as Pangea, and surrounded on all sides by open water.

As those lands converged, immense pressure pushed

the Earth’s crust upwards, creating what would eventually become

the gentle rolling slopes of our modern Appalachian Mountains.

Back then, though—about 200 million years ago—these ridgelines

reached up as high as the Himalayas.

Over the epochs that followed, tectonic shifts caused the terrain

to pull apart again, and those towering peaks eroded with

it, their tippy-top sediments hauled east for a hundred miles to form the Atlantic Coastal Plain, on which we now sit. But picture this: our beaches ending

not at Ocean City, but rather out on the edge of the continental shelf,

where the land ended, the water still gets deep, and the early Atlantic

originally began.

What did Maryland look like back then? “It changes through

time,” says Carl Hobbs, geology professor emeritus at the Virginia

Institute of Marine Science. Over the eons, swings between

ice ages and global warming fluctuated sea levels by

hundreds of feet. As glaciers melted, their runoff carved the

ancestral Susquehanna River out of the land, and that over time, its valley would

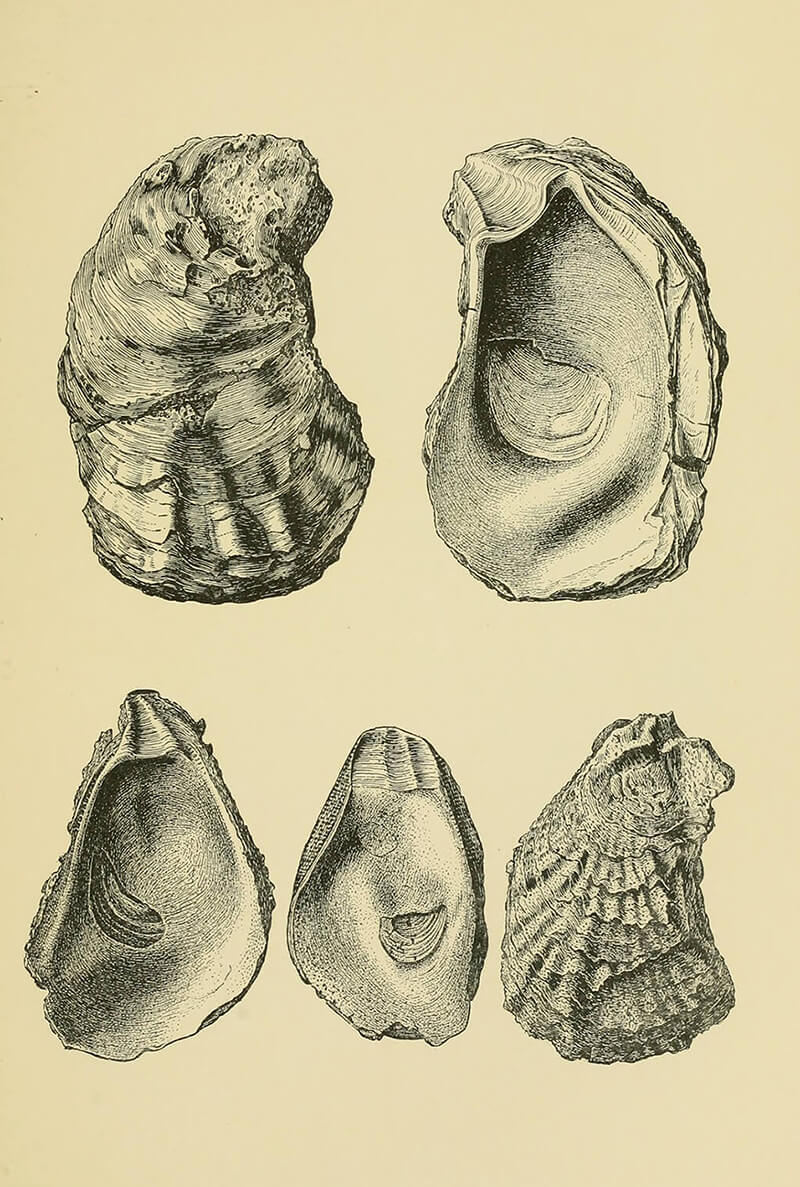

eventually become the Chesapeake. At times, too, a shallow

ocean stretched west, filled with prehistoric sharks, whales,

and sea turtles. Its waves came right up to the high-elevation

“fall line”—think the Jones, Gwynns, and Gunpowder—that still cuts through

the heart of Baltimore, which was then surrounded by tropical rainforest.

MIOCENE ERA SHELLS OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY.-WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

But that all got interrupted 35 million years ago, when,

in a twist of geological fate, a meteor struck off the coast of what

we now know as southeast Virginia. As many as three miles

wide, this celestial rock crashed into the region at a staggering

76,000 miles per hour, leaving behind a crater twice the size of Rhode Island and as deep as the

Grand Canyon—“a hell of a

hole,” says Hobbs, and still the largest known in the United States. A

subsequent tsunami wiped out much of the life on land, though

it wasn’t a total loss.

While the meteor did not technically make the Bay, as is often rumored, that

cataclysmic impact would certainly influence its creation. Rivers flow downhill, so over time, the surrounding tributaries

shifted their directions to convene at this new depression,

near the future mouth of the Chesapeake. Before

that, the Susquehanna had hooked a left and headed right

out to the ocean, over what is

now the Eastern Shore—no Bay required.

At that time, the Delmarva Peninsula didn’t exist

yet. It would only show up over the last two million years,

when glaciers sometimes reached as far south as Pennsylvania.

Their mile-thick ice sheets pressed down on the

Earth’s crust, once again pushing up sediment, which,

over periods of rising seas, slowly sifted down the coast.

Above the drowned Atlantic Coastal Plain, the Eastern Shore is essentially an ancient sandbar, sitting atop the long-lost crests of Appalachia.

In fact, it is ultimately the Shore that deserves credit for establishing

the Chesapeake. Because without its 170-mile lowlands

to both protect our state’s western edges from Atlantic

waves and direct nearby tributaries towards its southern

tip, an estuary might have never formed here. Who

knows—Baltimore could have been a beach town, as up

and down the western shore, “Those long rises of land

that you can trace for hundreds of miles,” says Hobbs,

“are old ocean shorelines.” Instead, we live between a

quiet harbor and that looming fall line, where a supercontinent

once stood, its enduring elevations now tumbling

into tributaries toward the Bay.

And believe it or not, that big body of water is still

changing. Glaciers continue to recede from some 20,000

years ago, and as the load has lightened on the Earth’s

surface, parts of the Atlantic Coastal Plain slowly settle

and, with the help of a warming climate and rising sea levels, begin

to sink.

Always, too, there are currents, tides, winds, and

rains that erode the land in one corner and deposit it in

another. Old channels fill in. New sandbars curl out.

And humans, of course, have an impact.

Today, the Chesapeake Bay proper is 200 miles long,

ranging from three to 30 miles wide, with an average

depth of only 21 feet. Below that bottom, traces of the old

Susquehanna remain, its deep canyon slowly filled in

with layers of time.

“Are we done?” says Ortt. “No. This is history.

And the process is ongoing.”