A severe shortage of cancer therapies is forcing thousands of patients to miss life-saving treatments, several leading healthcare organisations have warned.

There are 14 oncology medicines listed “in shortage” by US regulators, including the generic chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and carboplatin, which are first-line treatments for many common types of cancer.

Julie Gralow, chief medical officer at the American Society of Clinical Oncology, said hospitals were already rationing some drugs and doctors were being forced to make difficult decisions about delaying chemotherapy treatment or using substitute medicines, which may not be as effective.

“The concern there, of course, on the part of patients and their clinicians is: ‘are we sure this [substitute drug] is equally effective? Are we potentially in some way reducing the chance for cure?’ I don’t think we have solid data on that but that is a serious concern.”

Gralow said the crisis was particularly acute due to the widespread use of chemotherapy drugs. Between 100,000 and 500,000 patients could be affected by shortages of cisplatin and carboplatin, highlighting the urgent need for policymakers to strengthen supply chains, she said.

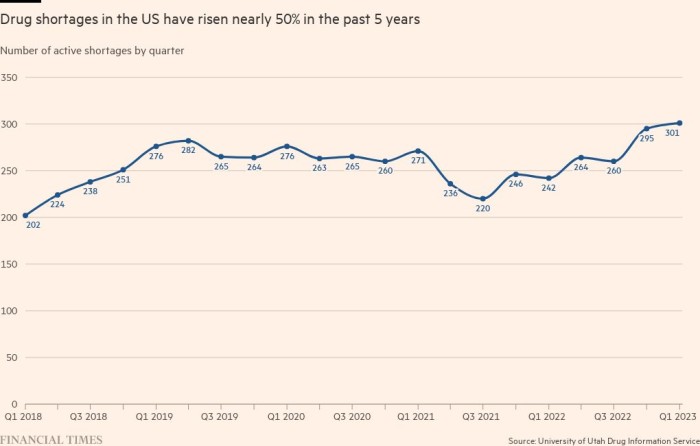

Drug shortages are not new. But experts warn a growing reliance on offshore manufacturing, increasing demand, market consolidation and pricing pressure has made the US particularly vulnerable to them.

There were 301 drugs across all therapeutic areas listed as “in shortage” at the end of March, which is the highest number in almost a decade, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

The Society of Gynecologic Oncology, which is conducting a survey to determine the extent of the crisis, said initial results found shortages of key cancer drugs across 40 US states.

“This is a public health crisis. We have never seen a shortage like this one,” said Angeles Alvarez Secord, president of the society.

Some newly developed oncology treatments, such as Novartis’s prostate cancer therapy Pluvicto, are in shortage. The company stopped taking on new patients in February following quality control issues flagged by the US Food and Drug Administration at two manufacturing sites.

But supply chain experts say generic drugs, which require complex manufacturing processes to make and yet tend to be sold very cheaply, are most vulnerable to shortages. They make up 90 per cent of all drugs sold in the US but just 18 per cent of all drug costs, according to a March report by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

“We need to rethink the entire marketplace for generics, which is where most of the shortages can be found,” said Laura Bray, founder of Angels for Change, a non-profit group advocating for action to end drug shortages.

She said the generics industry had become a race to the bottom on price that made quality control more difficult, particularly for complex medicines such as chemotherapy drugs. When only a handful of companies supply a medicine a single event can cause the type of “perfect storm event”, which is occurring with chemotherapy drugs, said Bray.

Most generic companies rely on active pharmaceutical ingredients produced in lower-cost countries, mainly China and India, to make drugs.

The cisplatin shortage is linked to quality control problems at a factory in India run by Intas Pharmaceuticals, which provides around half of the US’s entire supply of the chemotherapy drug. The company ceased production of cisplatin and carboplatin destined for the US following an inspection by the FDA in December, which detailed a “cascade of failure” in its quality control unit.

Intas and its US subsidiary Accord Healthcare said they were working with the FDA on a plan to return to manufacturing.

Oncologists say they found it more difficult to obtain supplies of both chemotherapy drugs soon after Intas production was suspended.

“In late April and May for newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients I had to make drug substitutions because we did not have the sort of first-choice drugs available,” said Jennifer Rubatt, an oncology specialist in Denver, Colorado.

She said patients reported more severe side effects when using the substitute drugs, rather than the platinum-based chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and carboplatin.

One cancer patient who lives in Sacramento, California, told the Financial Times he was taken off cisplatin in April because his condition was not deemed curable by his healthcare provider, Kaiser Permanente.

“Cisplatin is now under protocol reserved for curable cancers. And since mine is not curable, it’s not something I’ve qualified for at the moment,” said Michael Griffith, a 51-year-old father of three.

He said when he was previously taking cisplatin his oncologist told him the cancerous tumours in the bile ducts of his liver appeared to be “locked down”. But a recent CT scan suggested his tumour had grown slightly since he was taken off the chemotherapy drug, said Griffith.

Griffith’s healthcare provider Kaiser Permanente said it could not comment on individual cases but recognised that any time there was a national shortage of a medication patients affected “may feel anxious”.

“Our physicians and pharmacists are working with their patients to ensure their treatment plan is as effective as possible and to identify alternative treatments when necessary,” it added.

The scale of the cancer drug shortage is prompting authorities to consider short-term fixes. The FDA is mulling allowing importation of chemotherapy drugs from foreign manufacturers that are not currently approved to distribute in the US on a temporary basis.

But health experts and the generics industry say fundamental reforms are needed to encourage manufacturers to stay in the market to strengthen supply chains. The closure in April of a big US generics company Akorn Pharmaceuticals and Teva Pharmaceuticals’ decision last month to trim its generics portfolio highlight the extreme pressure the industry is under, they say.

“A consistent thread here is pricing and vulnerability. Typically what you see is market forces driving down prices, which is great for patients and everyone involved, except for manufacturers,” said Craig Burton, senior vice-president of policy and alliances at Association for Accessible Medicines.

When only one or two manufacturers were left in a market for a drug then if something happened you had a greater risk of shortages, he said.

A Senate hearing on the drugs shortage crisis in March raised the prospect of providing tax incentives to encourage investment in more US-based production or mandating stockpiling of critical medicines.

Burton said consolidation in the drugs purchasing market had enabled bulk purchasers to squeeze manufacturers on price in both the retail and hospitals market.

Three big purchasing groups — Red Oak Sourcing, the Walgreens Boots Alliance Development and ClarusOne, which includes Walmart and McKeeson — control about 90 per cent of the retail prescription market. The market to supply generics to hospitals is similarly concentrated.

For cancer patients like Griffith, who fear their lives could be shortened because they can’t access standard-of-care chemotherapy drugs, change can’t come soon enough.

“This is weighing on my mind everyday. I just don’t know why the country, an association or the FDA wouldn’t step in for the greater good?” said Griffith.