THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN

VIII.

There had been much talk in early August of Dadabhai Naoroji, the Indian Home Ruler, who was presenting himself before an Irish constituency with plans to run for office. There were some notable names who thought Naoroji had a chance, namely the Irish republican activist, Michael Davitt. As the Voice of India noted: “The case of Ireland and that of India is not far too different.” Maud Gonne wanted to get to work for Ireland quickly. From what W.T. Stead had told her, she thought Michael Davitt would be the best person to see. As she prepared to leave the Continent, she reflected on the eventful year.

ROYAT

Health Spa at Royat.

It was a sultry summer day in 1887 when, Maud, her sister Kathleen, and Aunt Mary, arrived at The Royat in Auvergne. She was recovering from tuberculosis, and it was here where her doctor advised her to take a rest cure. The Puy de Dome flitted in a shimmering haze of heat. She was tired but felt strangely excited.

They sat beneath the trees in the promenade listening to the band and watching the people slowly walking up and down the street.

“Something tremendous is going to happen to me,” Maud told Kathleen. “I don’t know if it is good or had.”

“It is the ominous feeling before a thunderstorm,” Kathleen replied.

“No,” said Maud, “no, it is more than that.”

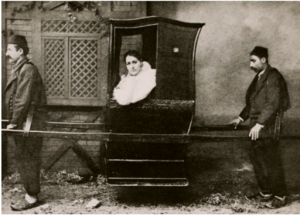

Maud.

A friend of Aunt Mary, Madame Féline, the wife of a French general, and her daughter, Berthe, came and sat with them. They were also taking the cure.

They sat fanning themselves with the great black fans.

Spa.

“It is too hot to go to the play at the Casino tonight,” said Aunt Mary.

“There is a storm coming up,” said Madame Féline. “I hate thunderstorms and they are terrible in Auvergne.”

Two Frenchmen came up and introduced themselves. Maud was certain she had met one of the Frenchmen before, the one named Millevoye, a tall man, probably in his late 30s, who looked very ill.

“Have we met somewhere before,” Maud at last asked him.

“No, mademoiselle, it is impossible,” Millevoye said. “I would never have forgotten if I had met you.”

“But you have,” Maud repeated. “Somewhere, sometime, but it is too hot to think.”

A few thick drops of rain began to fall.

“It would be well to go in before the storm,” said Aunt Mary.

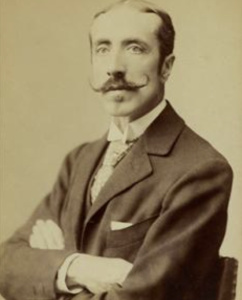

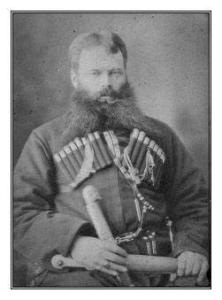

Millevoye.

The two Frenchmen accompanied them to their hotel.

A great flash of lightning illuminated the sky just as soon as they reached the entrance, it was followed with a crash of thunder and torrents of rain.

“Come in and wait until the storm abates,” Aunt Mary implored the Frenchmen.

The blinds and curtains in the salon windows were drawn, and the gas-light was switched on to keep out the sight of the storm, but the thunder shook the place.

Aunt Mary’s secretary began playing the piano, but Maud loved storms, so she quietly slipped out to the roofed-in terrace through the thick curtains of the parlor.

Garden at Royat.

The lightning was continuous. The unending thunder cried back in echoes from the neighboring mountains. Marauding rain scalped the rose petals in the garden, producing a fragrance that was intoxicatingly sweet. It was the most wonderful storm Maud had ever seen. “It would be such a lovely shower bath,” she thought, as a strong longing took over her to join the havoc in the garden. The thought of her new hat and dress, however, restrained her from acting on impulse, so she stretched her bare arms out into the rain.

“Mademoiselle,” came a voice from behind her, “your aunt has sent me to look for you and to tell you to come in.”

It was Millevoye.

“But how can one leave a storm like this?”

“Yes, it is much better here than inside if you are not afraid of the storm,” said Millevoye. “Are you afraid of anything?”

Maud shook her head and repeated the admonition of her late-father. “You must never be afraid of anything, even of death.” Their eyes locked. “Tell me, where have we met before? I have met you, try and remember.”

Millevoye put his arm around Maud and kissed her dripping wet arm.

“Let us go in, Aunt Mary will be anxious,” said Maud, turning away. “You don’t understand. We speak a different language.”

They returned to the hot hotel salon.

BOULANGER

Every day at the springs that summer, Maud met Millevoye, and they walked along the promenades together. Maud told him that she wanted to be an actress. Millevoye, too, revealed his dreams and aspirations. He came of a Bonapartist family and spoke bitterly of the compromise and corruption among the politicians of the Third Republic.

“The whole ambition of my life is to win back Alsace-Lorraine for France. A nation who relinquishes one inch of its territory is unworthy and decadent,” said Millevoye, “until it regains it.” He hero-worshipped Napoleon, but had, himself, no beliefs in hereditary rights of kings or emperors. “At times, the genius of a nation incarnates itself in a man; outstanding genius alone gives the right to rule despotically. The greatness of nations depends on their willingness to recognize this,” he would say.

“If only you were French, together we would win back Alsace-Lorraine for France,” he told Maud one day. “With the help of a woman like you, a man could accomplish anything.”

“I am Irish,” she said, “the whole of my country is enslaved and even your Napoleon could not liberate her.”

“Napoleon would have freed Ireland as he freed the other nations if he had not been defeated,” said Millevoye. “Perhaps he thought he was striking a blow at the heart of the English when he went to Egypt. That was his mistake—he should have gone to Ireland.”

Millevoye hated the English because they defeated Napoleon.

“Why don’t you free Ireland as Joan of Arc freed France?” said Millevoye on another occasion. “You don’t understand your own power. To hear a woman like you talking of going on the stage is infamous. Yes, you might become a great actress but if you became as great an actress as Sara Bernhardt, what of it? An actress is only imitating other people’s emotions; that is not living; that is only being a cabotine, nothing else. Have a more worthy ambition, free your own country, free Ireland.”

Maud was silent.

“Let us make an alliance,” Millevoye continued. “I will help you to free Ireland. You will help me to regain Alsace- Lorraine.”

“But we have different enemies,” Maud said. “How can we eat up England and Germany at once?”

“They are not so different, the Teutons and the Anglo-Saxons,” he replied. “England defeated Napoleon and his whole dream of a liberated Europe. England encouraged Bismarck in order to keep France and Germany at enmity. Germany is only the incidental; England is the hereditary enemy of France.”

“Now we speak the same language,” said Maud, taking both of his hands. “I accept this alliance against the British Empire. It is a pact to death.”

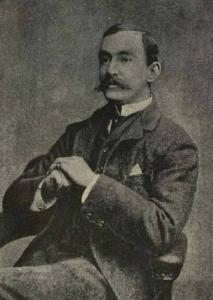

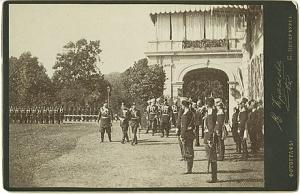

General Georges Ernest Boulanger.

General Georges Boulanger was at Clermont-Ferrand at the time forming a political party. Nicknamed Générale Revanche (“General Revenge,”) for his aggressive nationalist response to France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, Boulanger was a popular public figure whom many European nations feared would declare himself dictator. Millevoye, one of Boulanger’s chief supporters, wanted Maud to meet him. A dinner was planned at a country mill house owned by a woman who wore the national dress of Auvergne, that is, a big ribbon bow. She was an attractive and intelligent woman who was a great admirer of Boulanger, and the woman Boulanger loved, Madame do Bonnemain.

Maud had to use some diplomacy to avoid Aunt Mary from being invited to the dinner. Madame Féline’s excursion to the mountains, which Maud, Kathleen, and Aunt Mary, were all invited, provided a perfect opportunity.

“The excursion is too tiring for me,” Maud explained.

Maud found General Boulanger a good-looking man, with fair hair, steady grey eyes, and a charming manner.

“I do not think he possesses the hard-mindedness required for the role his party hopes he will play,” Maud confessed to Millevoye after the dinner.

“It depends on Madame Bonnemains,” Millevoye replied. “If she is strong enough for the role, all will be well—he is crazy about her.”

Aunt Mary never heard of the dinner, nor of Maud meeting General Boulanger.

MARSEILLE

Marseille.1

Maud was just regaining health and preparing to leave Royat. She was going to Constantinople to visit her childhood friend, Lilia White, the daughter of Sir William White, the British Ambassador. When Lilia heard of Maud’s illness, she wrote asking her to come and stay with her, as her mother was going away for several months, and her father thought they would be happy together.

Millevoye, who was addressing a series of meetings in the south of France, came to see her off at Marseilles.

He knew the town well.

They visited Vieux Port and ate bouillabaisse in a strange sailor’s restaurant with a clever little parrot. The bird sang all the words of the Marseillaise. (Its other vocabulary was more lurid, but equally impressive.) Every house it seemed had strange birds and pets, living souvenirs which the French sailors brought home from distant lands. Because of this, Marseille had no shortage of animal shops. Maud bought a little marmoset monkey.

“I will name him Chaperone.”

“Why Chaperone?” asked Millevoye.

“It was only by considerable strategy and a few lies that I managed to get this free day in Marseilles,” Maud replied. “In respect for convention, I need a chaperone.”

Marseilles seemed like such an idyllic place, where even the poorest of people looked happy.

All the women had their hair beautifully waved, and elaborately dressed.

“Even the market women go to the coiffeur each morning,” Millevoye explained, “and pay a low pence to have their hair properly done.”

Millevoye then went to an armorer, spending a great deal of time selecting a small revolver.

“Why are you looking for a revolver,” Maud asked. “You have a good one, I see that you carry it on you at all times.”

When Millevoye left her at the boat, he put the gun into her hand.

“It is to protect our alliance. Promise me you will always carry it,” he said. “No woman should ever travel without a revolver.”

“I will not forget our alliance,” said Maud. “I shall only be away for a month. I will see you before I return to Ireland.”

Marseille. 2

Thousands of oranges were floating on the surface of a deep blue sea.

“Did some boat laden with oranges sink?” Maud asked the Captain.

“No,” said the Captain, “When there are too many oranges to be sold on the market, they are dumped into the sea by the merchants to get rid of them.”

Maud thought of what her Aunt Augusta once told her: “Fruit is an expensive luxury and should be indulged in sparingly.” The oranges should have been given away to children who loved them instead of being sent floating away to sea, Maud thought. She retired to her cabin and busied herself by watching little Chaperone’s antics. The sea got rougher and rougher. “I don’t think I like storms at sea,” Maud told the monkey, who didn’t seem to mind it at all. “Oh, Chaperone, I am miserable. I hope it is not like this for the rest of the voyage. We have six whole days and nights until we reach Constantinople.” When the stewardess knocked at the cabin door, she was barely able to answer it.

“Miss Gonne,” she said, “dinner service will begin at six this evening.”

“I won’t be able to attend,” mumbled Maud. “I suspect you needn’t trouble yourself with bringing me any either.”

The following morning the weather was still black. “It is a waste of life to remain confined to the four walls of this tiny cabin,” thought Maud. So, she staggered herself up to the deck, where she was saddened by the sight of a number of forlorn little swallows draggled on the ground. She picked one up and dried it off, which revived it a little. Then a girl from second class joined her. She was an Armenian orphan raised by French nuns and going out to another convent of the Order to teach French. She had never been outside the convent before. She was not older than fifteen years of age. Together they tried to feed the birds, now flightless from the storm, bread and milk. They were unsuccessful. The swallows died that evening. Maud and the little girl threw their tiny bodies into the sea. The girl began to cry, so Maud gave the child her old silver rosary beads to console her.

“Captain,” Maud asked at dinner, “when do you expect our arrival in Syra.”

The Greek city was their first stopping place.

“Tomorrow,” the Captain replied, “but the storm has made us late. “We shall only stay for coaling.” The Captain saw Maud’s eagerness. “You mustn’t go ashore. It isn’t at all safe for ladies. Some very unpleasant things have happened at Syra, and I have been obliged to forbid all lady passengers going ashore there.”

Maud then remembered the second in command, a bearded Corsican named Petru with fine eyes and the countenance of a brigand. He had been very attentive to her during the trip; leaning over the rail in the darkness of night, they once discussed Napoleon, whose memory Petru worshipped. Maud ventured to ask him about landing at Syra; for the one thing that she longed for was to be on solid land.

“No, no, Mademoiselle,” said Petru. “The Captain’s orders are absolute. He is right; no ladies may land, and you are too beautiful. Perhaps…if I could take you…but that is impossible. We are all too busy. No one may go ashore.”

Maud retired early to her cabin with Chaperone and the Armenian orphan. The next morning the sun shined brightly, but there was no land in sight. An old Turk with a long grey beard was strolling along the deck. A large canvas awning was arranged behind him, sheltering the ladies of his harem from indiscreet gaze. He was a clearly a person of consequence. Maud did not think that he would help her to land, but she thought it would be amusing to meet the ladies of his harem. The old Turk looked at Maud gravely, paternalistic even, as he passed. Maud introduced herself, and the man did likewise. Edric Bey was his name. They spoke a little and she told him the nature of her trip.

“I am visiting the daughter of the British Ambassador,” she told him. She did not ask him about landing at Syra, or even about visiting his wives. Maud thought it wiser to approach the stewardess for such an introduction. Besides, it seemed to Maud that the advance should come from the ladies themselves.

SYRA

Greek peddler.

At five p.m. they stopped at Syra. The ship was immediately surrounded by crowds of boats full of Levantine peddlers selling all manner of things to the passengers stranded on the deck.

The coaling barge was busy at one end, and it would take about two or three hours before the ship would start again.

One of the Greek peddlers, Kharoun, who spoke some Italian, smiled at Maud ingratiatingly, and offered his wares.

Maud showed him a fifty-franc note and pointed to the shore.

They struck a bargain.

In exchange for the note, Kharoun would row her to Syra and back.

Syra from the sea.

In the confusion of the crowd, Maud slipped down the ladder and into his boat unnoticed. Chaperone sat on her shoulder, sheltered in her long black veil. It was a habit of hers to wear such a covering (instead of a hat) when traveling to keep the dust off her hair. She was soon on shore. It was great to be on land again. She went to the post office and sent off postcards, and happily wandered among the shops in dark, labyrinthine streets. She purchased Turkish delight, pots of rose-leaf jam, cigarettes, and flowers. Kharoun acted as her cicerone, and she was glad to be rid of him at last in a cafe on the harbor where she could keep an eye on our ship while drinking coffee and eating strange cakes. She had been on land for two hours, and the herd of peddler-boats around the ship were thinning out, but her Greek guide had not returned.

Syra.

“He must be drinking wine somewhere,” Maud thought. “Have you seen the gentleman who arrived with me?” Maud asked the waiter as paid her bill. The waiter, who spoke only Greek, was of no assistance. Maud decided to go down to the place where they first landed, where Kharoun had left his boat. She had not paid him yet, so she was confident that he would turn up eventually. Sure enough, he was there, along with two other sailors sitting in the boat. Maud got in and told him to start. Kharoun was in no hurry.

“There is plenty of time,” he said.

“Start at once,” Maud demanded.

“Nomízei óti eínai vasílissa,” said Kharoun, laughing with the other sailors who began to lazily row.

The lights on the sea were enchanting. Syra looked fairy-like.

Maud was happy.

Maud was happy until she noticed the sailors were rowing in the opposite direction of her ship.

Kharoun sat on the scat facing her. He was not rowing this time.

“Go there!” said Maud, pointing to the ship. “Tell them to go there!”

Kharoun smiled. “We are going to show you a beautiful point of view.”

“Turn the boat at once!” yelled Maud.

Kharoun only laughed. His men rowed even quicker in the direction away from the ship.

Kharoun’s betrayal.

Maud stood up. She pulled the revolver which Millevoye had given her from her pocket and aimed it at Kharoun. “Obey, or I fire.”

The men stopped rowing.

“Eínai vasílissa,” they stammered quickly. “Eínai mia trelí vasílissa!”

They swiftly turned the boat around rowed to the ship.

Maud sat down, but kept her revolver pointed at them, never taking her eyes off Kharoun. When they were at the ship’s side, Maud tossed him the fifty-franc note and scrambled up the ladder while the sailors passed around her discarded parcels.

At the top of the ladder Maud found Petru waiting for her. “Mademoiselle, you almost missed the boat,” he said. “The Captain knows. He is very angry.”

Climbing Side of Boat.

The Captain was coldly severe about Maud’s disregard of his orders at dinner that evening.

“I am not a sailor like yourself,” said Maud. “I had such a terrible nostalgia to be on land that I cannot expect men who are used to the sea to understand. It is my first voyage, and I was all alone. You must forgive.”

The Captain did forgive her, and with good grace.

“You are very young,” he said with a sigh. “You do not understand the danger. I hope you will not try it again at Smyrna, but if you do land, I suggest you find a proper escort. None of these ports are safe for young women alone.”

HAREM

Maud turned her attention to getting inside the harem of Edric Bey. She asked the stewardess who was admitted to their room, to tell the ladies about her monkey, Chaperone.

The next day the stewardess brought an invitation from the ladies to visit them, and to bring Chaperone.

The awning was lifted by Edric Bey himself. Inside Maud found his two wives and his mother, a very old woman, seated on many cushions. His wives spoke French and were thrilled over Chaperone. Maud brought a box of Turkish delight and some of the dowers that she purchased at Syra. Edric Bey made lemon sherbets from fresh lemons in a silver howl. Naturally, the talk was limited, strictly conventional, and chiefly between Edric Bey and herself.

Turkish Harem.

“We have a house in Marseilles where I carried on business,” Edric Bey explained. “We are returning to Turkey because my mother wants to go home.”

“We are all glad to go home,” said the first wife, “though France is a very nice country.”

It was an altogether dull visit. Maud knew she would not get a chance to speak with the women while Edric Bey so courteously insisted on playing the host.

“You must come again and sit with us,” he said when Maud left to dress for dinner. “It is more agreeable under the awning than in the ship saloon. We live here. There is more air than in the cabins.”

“Do you never take a walk on deck?” Maud asked the first wife.

“No,” she said. “Why should we? It is pleasanter here. We see the sea, we have the air, come back and see us and bring the marmoset.”

SMYRNA

The next morning the stewardess brought Maud a box of French chocolates. It was a gift from the Turkish ladies, and had an invitation attached to visit them again. But they were nearing Smyrna, and Maud had to see about landing. Trying to avoid another unpleasant adventure, Maud decided to accept the Captain’s suggestion, and accept the escort of Leon and Conrad, two young German commercial travelers who had already been in Smyrna and knew their way about town. While Leon attended to business, Conrad escorted her through the bazaar, and they all met at lunch. The restaurant the young Germans selected evidently catered for tourists, for there was nothing Eastern about it.

“We must be careful where we take a lady,” said Leon, “but there is a very interesting sight full of local color to be seen at the gates of Smyrna.”

“The heads of six brigands, executed last week, are nailed on posts to put the fear of God or man into the heart of other brigands,” Conrad explained.

Smyrna.

This came in the wake of reports about the brigands of Smyrna who kidnapped four young Englishmen a month earlier.[3]

The conventional young Germans, to Maud’s surprise, offered to take her there by carriage after lunch.

Maud, who had a “horror for ugly sights,” declined the offer.

Her German friends, though slightly disappointed, thoroughly approved of what they considered her feminine shrinking, and admired her the more for it.

They filled the time walking around the bazaars. Conrad, infatuated with Maud, bought her sweets and flowers. Leon, who preferred seeing the heads of men over a man losing his head, went off to look at the bodiless brigands.

Maud appreciated Conrad’s unselfishness and “sense of duty” in not abandoning her to visit the “horrid sight.” He told her a lot about his business, and of the rivalry between his firm and a British firm selling the same goods. He was positively triumphant about a big order he recently secured for Germany.

“I spent a year in England learning English, so necessary in commerce,” said Conrad. “I like you English, although I am always up against them in trade.

“Oh,” said Maud, “I am not English.”

“Forgive me,” said Conrad, “but your accent…”

“I am the daughter of an Irish father and an English mother,” said Maud. She then elaborated. “John Mitchell once said: ‘You cannot have a British Empire and repudiate the conditions sine qua non. There stands your British Empire and here is what it costs; everyone can determine at his leisure whether it is worth the price.’ By the time I had arrived at the age of reason, I had determined that it was not worth the price. Every logical mind will assent to the proposition that omelets cannot continue to be manufactured without a continual breaking of eggs. No more can the British Empire stand or go without famine in Ireland, opium in China, torture in India, pauperism in England, disorder in Europe and…”[4]

“—And wars with Mahdists in Egypt,” interrupted Conrad.

“War in Egypt…in Sikkim…in Burma,” agreed Maud.

“You have been following the Stanley Expedition in the papers then?”

Press dispatches were printing regular updates of Stanley’s progress in Africa, Maud had a somewhat personal interest in the accounts. James Jameson, an old family acquaintance, had joined the expeditionary team, and sent back etchings and first-hand accounts of Stanley’s adventure.[5] Jameson and his sister, Maud’s childhood friend, Ida, were the grandchildren of John Jameson, founder of the famous Dublin whiskey distillery.[6]

“Their mother and mine had been great friends when they neighbored in Donnybrook,” said Maud.[7]

THE MAHDI

Egypt had been a part of the Ottoman Empire since 1517. Around the time of the Napoleonic Wars (1804-1815) a junior officer in the Ottoman army, a Balkan Turk named Muhammad Ali, was dispatched to Egypt to fight the French. After the Ottoman victory, a chaotic power vacuum was created in Egypt. Muhammad Ali successfully quelled the uprisings, and the Ottoman Sultan named him Wāli (governor) of Egypt in 1805. Muhammad Ali had loftier ambitions and assumed the title of Khedive (Viceroy,) of a government he called the Khedivate of Egypt. The Ottomans tolerated this (though they did not officially recognize the title.) Ali would implement revolutionary reforms which brought Egypt into closer contact with the mercantile and state actors of the West. Tensions between the Khedive and the Sultan grew, ultimately resulting in armed conflict. Ali’s army defeated the Sultan’s army in two major campaigns, and the ruler of the Ottomans confered upon Muhammad Ali the recognition of a hereditary right to rule Egypt and Sudan. Egypt was effectively a semi-autonomous country within the Ottoman Empire. In 1819 the Khedive invaded Sudan and heavily taxed the annexed people under the ensuing colonial system. Having learned something of the European’s conception of Egypt (and their fascination with its history) Ali borrowed heavily from the symbolism of Egypt’s ancient past. He did this to further impress upon the mind of potential allies that the history of his land extended long into the forgotten past, that is, before the Ottomans and the Europeans (Muhammed Ali was the first to borrow the Egypt’s mythic vocabulary for use on official state records.) His efforts proved successful, and soon European powers (British and French) worked with Egypt to create the Suez Canal (a project which meant that European powers no longer had to sail around Africa to reach India.)[8] In the 1860s Khedive Isma’il (Ali’s grandson) followed in his grandfather’s footsteps, and commissioned Mustafa Salama al-Najjari to write a history of Egypt which repurposed the Hermetic tradition as a patriotic one. In connection with this (and to commemorate the opening of the Suez Canal) Khedive Isma’il commissioned Giuseppe Verdi to write the opera Aida to premier in the new Khedival Opera House. The Khedivial instrumentalization of European culture through political aesthetics was a political statement meant to embody a spirit of nationalism and independence.[9]’[10]

The Khedive also embarked on campaign to eradicate slavery in Egypt under the sphere of operations organized in Khartoum (Legitimate trade was accompanied by slave-raiding, and these merchants were the virtual rulers of the districts in which they traded.) The Khedive appointed the British explorer, Sir Samuel Baker, to lead an expedition to facilitate a trade route to the Upper Nile and to suppress the slave trade in Sudan. Besides the practical difficulties of enforcing such an edict, slavery was an institution which was halal (permitted) in Islam, and the appointment of a Christian to suppress said institution caused resentment among the peoples of Sudan, as slavery was a major source of income for them at the time.[11]

The growing resentment of his people toward outside influences was not the only problem which the Khedive faced. His modernization projects had placed Egypt in debt. The British swept in to pay the debt in return for a controlling share of the Suez Canal. Egypt was under new management. The British effectively became the administrators of Egyptian fiscal affairs. In 1873 the British government established a joint debt commission with the other European shareholders, the French. The British then named General Charles Gordon as Governor of Sudan, who fought several battles with Sebehr Rahma, a native chieftain of Darfur. In 1879 the Anglo-French debt-commission forced Khedive Isma’il to abdicate in favor of his son Tawfiq. Political turmoil followed. General Gordon’s popularity among the ethnic Sudanese minority plummeted, and he resigned in 1880. This did not alleviate the anger and discontent among the people. Relations between the Egyptians and the Sudanese rapidly deteriorated, but the British now refused to get involved. Earl Granville (British Foreign Secretary) declaring: “Her Majesty’s Government are in no way responsible for operations in the Sudan.”

Muhammad Ahmad.

Things reached a tipping point in 1881. An Islamic revivalist movement had developed in response to the perceived heterodox practices of the Khedive and his un-Islamic policies. A spiritual leader named Muhammad Ahmad declared himself the prophesied Mahdi (a messianic figure who features in Islamic eschatology and believed to herald the end of times and cleanse the world of injustice and sin) and declared a Jihad against the Ottoman/Khedivate oppressors and their allies. In the 1880s the Mahdi and his followers (known self-referentially as Sufis and later Ansā) whom the British called Mahdists had established a vast Islamic State which stretched from the Red Sea to Central Africa.[12]

Charles Gordon.

In 1884 the British sent Charles Gordon to evacuate British garrisons in Sudan. Gordon’s hubris resulted in his death at Khartoum by the Mahdi’s forces. The British launched expeditionary missions in 1885, but these resulted in failure.

James Jameson.

In 1886 the Stanley Expedition set out to rescue Emin Pasha, the Egyptian governor of Equatoria (Southern Sudan.) It was this, the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, to which Jameson belonged.

CONSTANTINOPLE

Maud met Lilia at the port of Constantinople. Her old friend was accompanied by a young secretary from the Embassy and their guard.

“Mahmoud will get your baggage.”

A large Albanian man soon appeared in the customs house. Every Turkish official dropped whatever they were doing and went scurrying in search of Maud’s bags. They were soon loaded into the Embassy carriage.

“An Embassy kavass is a privileged person,” said Lilia. “Mahmoud is responsible to the Turkish Government for the safety of the Minister and all his staff. If anything happens to us, he might lose his head.”

Maud was fascinated.

“Like most Albanians,” said Lilia, “Mahmoud knows how to handle the Turks.”

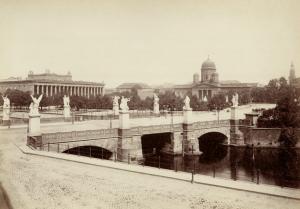

“Galata Bridge. View from the Eminönü side of the bridge in the Old City.”

Mahmoud’s methods, though efficient, were decidedly brusque. He sprang to the box, screaming and swinging his arms until the people who had circled their carriage reluctantly gave way. Maud was afraid they would run somebody down as they charged ahead through the crammed and jammed street—men in the costumes of a hundred nationalities, women veiled and unveiled, gilded, and inlaid sedan chairs on the shoulders of bearers, horses, oxen, donkeys, and pariah dogs everywhere. Some were limping on three legs, some had lost an ear or a tail, some had great open sores and lay in the sun licking them. Many were nosing in piles of filth, seeking something to eat. [13]

The ensuing days were pleasant. That Friday they drove to the Sadâbad on the far northern end of the Golden Horn, a place the Europeans called the “Sweet Waters,” where the Turkish ladies, veiled in thin yashmaks, used to ride. As enterprising as Maud was, she was not successful in getting to know any of the Turkish women. She did meet a few Turkish men at the occasional parties at the Embassies, but “an invisible barrier twisted which never for a moment was lowered.”

Turkish Lady Wearing Yashmak and Feredje. 14

“Mother and I had been received by the ladles in one or two of the great harems,” Lilia told Maud. “From what you’ve told me, it would seem we got to know those ladies even less than you got to know the Turkish family on your boat.”

This was not a concern for Lilia. She wasn’t interested. She just became engaged to a young Scandinavian in the diplomatic service. She was very anxious to find a fiancé for Maud among the many young eligible secretaries of the Embassies.

“Marriage,” said Maud, “is the last thing I am thinking about.”

“You are such a strange girl,” said Lilia.

Sometimes Maud and Lilia went for walks around the city, but always preceded by Mahmoud, in splendid Eastern dress and a long staff which he used to push people on the footpaths before them if they didn’t move away’ quick enough.

Maud hated it.

“Why can’t we go out without him?” Maud asked.

“No, it is the custom here,” she replied. “Father wouldn’t like us to go out without a kavass.”

Maud asked Sir White about it at dinner.

“It is the custom,” he said, “foreigners are not liked here.”

“No wonder,” said Maud, “if they have a Kavass with them.”

Mahmoud the Kavass. 15

It was only when Maud made friends with the wife of a German professor of archaeology who was living in Constantinople that she found a way of circumventing the Kavass. She would have them to accompany her to her house and say that she was spending the day with her, and that she would see her home.

The wife of the German professor went about unaccompanied and untroubled. She knew Constantinople well. She took Maud to visit the bazaars and the eastern part of the city, but even she, who was fluent in Turkish, “never penetrated the real life of the East.” They made friends with the pariah dogs who lived in packs and acted as scavengers in the different quarters of the city. Maud learned that in Turkish eyes, dogs brought luck. Ottoman officials once tried removing five thousand to an island, but a disaster immediately befell the city and the citizens said: “Those dogs ought never to have been taken away.” Since then, they had scavenged unmolested.” [16]

They were friendly, and Maud found the idea of annexing a puppy to add to her menagerie with Chaperone terribly tempting.

“Dogs of the Streets in Istanbul.”17

To amuse themselves, Maud and Lilia used to dress up as Turkish ladies and wander in the Embassy gardens. Maud had almost persuaded Lilia to go out costumed and make a surprise visit to some of their friends, but Sir William, when he learned of the scheme, very seriously forbade it.

“If you were taken for Turkish women and did anything outside the very carefully prescribed etiquette, any Turk would have the right to arrest you and hand you over to the police. You must give me your word that you will not try such a thing.”

Maud and Lilia were forced to be content at dressing up as Turkish princesses in the Embassy gardens, but that, too, was stopped by Sir White.

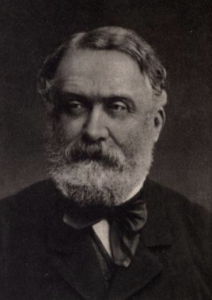

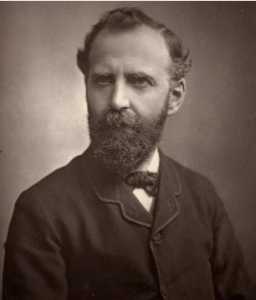

Sir William Arthur White.

“You girls are creating a serious scandal for me,” he laughingly told Maud and Lilia. “There is whispering in Embassy circles that the English Ambassador is secretly keeping a harem.”

A happy month rolled along in Constantinople, where Maud sailed with Lilia on the Bosphorus, and rode on horseback in the Turkish countryside with young people from the Austrian, Italian and German Embassies. She visited Ottoman palaces, where all the furniture works of art, and where they were received ceremoniously by State officials who served them rose-jam in crystal bowls and Turkish coffee in tiny porcelain cups called kahve fincanı.

Oscar Straus. 18

One of the people she met was Oscar Straus who, in 1887, became the first Jewish U.S. minister to Turkey. Straus received excellent business training in the Straus family crockery-importing concern at 42 Warren Street, New York City, and ran the American Legation like an office with regular hours. (Oscar’s two older brothers, Isidor and Nathan, would become the owners of Macy & Co. department stores in the following year.)[19] Straus quickly set to work persuading Sultan Abdul Hamid II to re-open several schools which had been closed in the Ottoman Empire. His most recent success was the successful petition on behalf of the American Colporteur missionaries whose agents were arrested, and their Bibles confiscated. Straus took the matter up with Kamil Pasha (the Grand Vizier) and the Sultan. He pointed out that the Bible had passed the censorship so there should be no objection to its sale. He also reminded the Kamil Pasha that the sale could only be stopped by a breach of their treaty amity and commerce with the Americans. “If Turkey wished to violate that treaty flagrantly,” said Straus, “he would immediately advise his government of this serious breach in our relationship and await instructions.” The Ottomans saw his point of view. A Vizierial degree was secured for the American missionaries.[20] An envoy’s success depended on whether or not he was persona grata to the Sultan, and Straus had accomplished a great deal on his first mission. Abdul Hamid was once asked whether he objected to the United States having sent a Jew. “Not at all,” he replied. “I’m delighted to receive one. In my mind there’s no difference between a Jew and a Christian. Both are infidels.” [21]

Sultan Abdul Hamid II

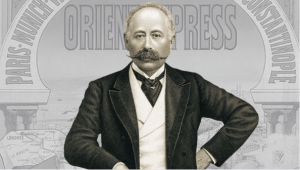

Maud’s visit coincided with the arrival in Constantinople of the German-Jewish financier and philanthropist, Baron Maurice de Hirsch.[22] He was in the city to adjust some financial differences with the Ottomans; his railway, “The Orient Express,” connecting Constantinople with European cities, was nearly complete. Straus helped find an arbitrator for the negotiations between Hirsch and the Sultan. As Straus would say: “The Turkish Government was hard-pressed for funds—its chronic condition.”[23]

Baron Maurice De Hirsch.

Through this encounter Straus and Hirsch developed a friendship. Hirsch and his wife Clara had recently lost their child; they declined official invitations but dined with Straus and his wife, Sarah. Hirsch told Straus that during his lifetime he wanted to devote his fortune to benevolent causes. His philanthropy up to that point was mainly bestowed in Russia, but he was desirous of doing something for the Russians who, because of Russian oppression, were emigrating to America. Hirsch wanted to enable them to reestablish themselves. In the coming years Straus would use his connections in New York to assist Hirsch with his philanthropic endeavors. [24]

Sarah Straus in Turkey. 25

In November 1887 attention at the British Embassy was drawn to a developing intrigue in the Imperial courts of Europe. A series of telegrams and letters were recently dispatched to high-ranking German officials and the German press which alleged to be from the German Chancellor, Prince Bismarck. These letters declared his intention to abandon Germany’s policy of Russian support in Bulgaria. This news was printed in the Kaiser’s own newspaper, The Cologne Gazette, in an article titled “Without Friendship and Without Enmity.”[26] Alexander III, the Russian Tsar, was furious. Bismack arranged for a personal meeting with the Tsar to discuss the matter in Berlin.[27] Bismarck assured the Tsar that the documents in question were forgeries. The Tsar was satisfied, but “speculation was rife as to who could have given them to the sovereign whose wrath, they had excited.”[28] On December 2, 1887, “the real nature of the forgeries by which the Tsar was misled,” was semi-officially telegraphed to all German papers. The Germans believed that it was the work of “a whole network of Orléanist (French Constitutional Monarchists) intrigue.”[29]

Bismarck & the Tsar.

“The present aspect of European affairs is rather puzzling,” said Sir White. “The best explanation I can offer is that Bismarck has tried to induce Russia to sit still and take a bribe while France is being crushed; and that Russia has declined. Next, he has tried to get Russia involved in the Balkan Peninsula; and here too he has failed. And now he is thinking what he shall try next. But I believe he is still true to the main principle of his policy, employing his neighbors to pull each other’s teeth out.”[30]

Sir White was particularly interested in this topic, as it was largely through his efforts that the war between Bulgaria and Serbia did not turn into a world war. His consistent policy was one of counteracting Russian influence in the Balkans by establishing a ring of independent states with a thriving nationalist spirit and supporting Austrian interests in the East.

“The Sultan now seems to be gradually becoming reconciled to the idea of a big Bulgaria,” said Sir White. “It is even said that he looks upon it as the best bulwark against Russia.”[31]

THE BULGARIAN CRISIS

To better understand this issue, we must first begin by looking at the people of the Balkans that were, until recently, within Ottoman lands. The European peoples of the East were long despised by the nations of the West. These people, the Schiavoni, were known by the Latin West as “Esclavons.” It was from this name that the word “esclave,” or “slave” derived. “It is no easy task to depict the intellectual qualities of this race, which strives for the sovereignty of the world with the Latins and Teutons,” scholars of the day stated. “It needs a long career of civilization to bring out the genius of races and nations in literature, in art, in political institutions.”[32] It was said that “their inferiority” stemmed from their geographical position, “standing as they did in the East…at the entrance of Europe… and the most exposed to invasions from Asia they were naturally the last to become civilized and the least deeply affected by civilization.” Philologists and ethnologists also believed that this produced an inferiority complex. “Feeling themselves unqualified to lay claim to the culture of modern Europe, some Slavs have claimed that of the ancient world. Certain Serb and Bulgar writers have taken it into their heads to demand as their rightful patrimony the greater part of Greek civilization from Thracian Orpheus to Macedonian Alexander.” This last statement was a reference to the burgeoning Pan-Slavic Illyrian movement. This religio-political idea had its roots in the work of the Bosnian ethnographer, Stefan Verković, whose influential work, Veda Slovena (1874 & 1881,) claimed to be one of the ancient Aryan Vedas.[33] This was published as tensions regarding identity mounted among the Southern Slavs.

In the winter of 1876-1877 a series of meetings were held between the Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Russia) known as the Constantinople Conference. The nature of the conference was to discuss the need for political reform in the volatile Ottoman territories with Bulgarians majorities. The Ottomans found the proposals disagreeable. This led to the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878,) which saw Russia and Serbia pitted against Turkey over autonomy for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Russia was victorious. Hostilities were concluded with the Treaty of San Stefano (1878) and the Treaty of Berlin (1878.) The independent, pro-Russian, Principality of Bulgaria was soon created out of the defeated Ottoman lands. At the request of Tsar Alexander II, his nephew, Prince Alexander of Battenberg, was named Prince of Bulgaria.

The growth of the Russian sphere of influence soon angered the other Balkan states and made the other Great Powers anxious. A war against Russia was prevented by the Treaty of Berlin (1878) which reworked the provisions of San Stefano. “Greater Bulgaria” was partitioned into the northern Principality of Bulgaria and two southern territories (Macedonia and Eastern Rumelia) under Ottoman control. Bosnia and Herzegovina were transferred to Austria-Hungary, and international recognition of the former Ottoman vassal states of Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro were declared. The treaty solved very little. Britain and Austria-Hungary were satisfied but that came at the expense of Russia (who felt cheated of their gains from the Russo-Turkish War) and the Balkan people. Other crises at a future time were all but ensured. The Balkan lands were now regarded in Europe as a matter for the disposal of the Great Powers, and greatly impacted the dynastic relations between Germany and Russia.

Alexander III, Franz Joseph and Wilhelm I in Skierniewice in 1884.

In 1881 Tsar Alexander II was assassinated. The new Russian Tsar, Alexander III, revived The League of Three Emperors (Russia: Alexander III, Austria-Hungary: Franz Joseph, Germany: Wilhelm I,) an alliance that provided mutual aid in the event of war on a member, and neutrality in the event that one of them became involved in a conflict outside the League. This meant Russia would remain neutral if Germany went to war with France, and that Germany and Austria-Hungary would remain neutral if Russia went to war with Britain. It also set the terms for consultation regarding any proposals for operations in the Balkans. In 1885 a coup took place in the Ottoman Province of Eastern Rumelia with the aid of the Bulgarians. The people of Eastern Rumelia proclaimed a union with the Principality of Bulgaria in defiance of the Treaty of Berlin. The delicate balance of power shifted. The Great Powers were worried that the Ottomans would retaliate in the Balkans and the Russians would aid the Bulgarians, resulting in another Russo-Turkish War. Unexpectedly, however, Bulgaria did not have the support of Russia. Alexander III did not warm feelings for the Bulgarian Prince like his father, and consequently withdrew Russian troops from the region. By 1887 relations between Bulgaria and Russia were on uneven footing at best. According to Sir White’s German friends, Russia had become “disgusted with the un- grateful kinsfolk she had liberated.”[34] Nevertheless, Germany’s recent perceived betrayal by Bismarck rattled the Russian Tsar.

NAPLES

On December 21, Maud turned twenty-one and inherited a trust fund of over £13,000 (and a sum from her mother’s estate.) She was now a very wealthy woman. After a month in Constantinople, Maud said goodbye to Lilia and was seen off on a boat for Naples.

Naples.

The mood in Italy was optimistic. The Italians were winning their war with Abyssinia (an opponent who was also at war with the Mahdists in Ethiopian frontier.) The Abyssinian Negus (Emperor,) Yohannes IV was also contending with resistance from his vassals, one of which recently signed a treaty of neutrality with Italy. Sir Samuel Baker told the press that December: “The English will never leave Egypt; and if the Italians knew how to make themselves masters of some points in Abyssinia, they will together be able to make good use of the enormous treasures of the Soudan. That country, thus placed between two fires, would certainly cease to oppose any civilizing influence or commercial enterprise.”[35] At Naples Maud found a telegram waiting for her from Millevoye. He wanted her to come to Paris at once. There was also an invitation from Madame Juliette Adam also asking her to come visit.

PARIS

Paris. Spring, 1888.

A great Republican, and friend of Léon Gambetta, Madame Adam, like Millevoye, was fervently anti-English and anti-German and believed that Russia was Europe’s only hope in defeating their dual-tyranny. As such, she endeavored to strengthen French and Russian relations, which she believed to be “a mystical union transcending ordinary human associations.” The fruit of her efforts could be found in her Franco-Russian Literary and Artistic Association, and through her public support of the Boulangerist-Cossack, Nikolai Ivanovich Achinov, or “the wondrous ogre Achinov,” as he was known among the Chancelleries of Europe. With the unofficial support of the Tsar, Achinov planned on taking advantage of the situation in Abyssinia by establishing a Russian colony called Sagallo near French Somaliland. In return for a grant of land and other privileges, Achinov would organize and instruct a military force to serve as a militia for the Negus of Abyssinia.[36]

The Boulangiste party was becoming a powerful force in France and were watched closely with suspicion by a French Government that was greatly under English influence. But they were not vigilant enough it seemed. Maud soon learned that Madam Adam was the mysterious person who sent the forged Bismarck letters to the Germans to sow the seeds of distrust between the Germany and Russia. Following the Berlin interview, the Boulangerists, “in order to counteract the effect of the repudiations of Prince Bismarck,” needed to send a secret dossier to St. Petersburg, “a certain proposals for a treaty with Russia,” which required hand-delivery to Konstantin Pobedonostsev, the Tsar’s chief adviser and head of the Holy Synod in Russia. That is where Maud came into play.[37]

Juliette Adam.

“We dare not trust the post with delivering it,” said Madame Adam. “It is very urgent and needs to be delivered at once. Will you undertake the mission?”

It was certainly against the whole of English diplomacy.

“Yes,” said Maud unhesitatingly

“The Tsar, whose mind reflects the great and untroubled soul of Russia,” said Madam Adam, “is well able to estimate at its true worth the insatiable greed of Germany and the ever-encroaching character of her ruler.”[38]

That very night Maud started for St. Petersburg with the dossier sewn into her dress.

Millevoye saw her off at the station.

“It is your first work for our alliance against the British Empire,” he said.

BERLIN

Berlin.

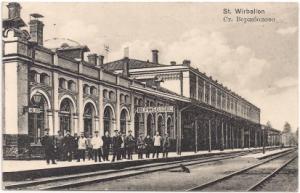

On the station platform in Berlin Maud noticed a man carrying an attaché case which he seemed careful not to let out of his hands. “It must have been a diplomatic valise,” thought Maud. The man joined the train and passed up and down the corridor several times. Each time he did so he looked at Maud and grasped his valise. In the morning they arrived in Wirballen, the frontier station where all passports were examined. Everyone got out of the train for this. Maud had with her an English passport which she got before leaving for Constantinople but, as she had been met there by the British Embassy people, her passport was never examined. No passports were required in other European countries, Russia alone insisted on passports. At Wirballen Maud confidently produced hers and was unprepared when the Russian official said (in a bad French) that it was not “en règle” as it had not been counter-signed in Paris as it should have been.

“You cannot enter Russia until this is counter-signed,” he told her.

“What am I to do?” thought Maud. “The papers stitched into my dress must be delivered by tomorrow.”

Madame Adam particularly insisted on this because the counter-proposals were being sent from Berlin and it was of urgent importance the French that the papers Maud was carrying should arrive first.

Wirballen.

Maud saw the man with the valise passing freely through the doorway from which she was denied entry. He was being saluted by the official examining passports as though he was a well-known person. Maud saw him pause at the doorway and look back at her.

“He is a Russian,” Maud thought. She smiled at him and beckoned him to come back.

“Come back,” said Maud. “Would you do me the great kindness of explaining to me what this passport official is saying, as I cannot understand.”

This he most obligingly did.

“Oh, thank you,” Maud said. “It means that I will have to wait here in Wirballen four days until my passport is sent back to Paris and returned with a vise.”

He nodded. “It is most unfortunate for Wirballen is a small place and you will find it uncomfortable.”

“Oh, I do not mind at all,” said Maud, smiling brightly. “I am in no hurry. I am only traveling to see Russia, and it will be quite amusing to see the life of a little frontier town. As for discomfort, I am too used to traveling to mind that. I shall be very well amused, Monsieur. I have only one regret, that I shall not have the pleasure of traveling the rest of the journey to St. Petersburg with so courteous a gentleman as yourself.”

Maud turned away towards the door leading out of the station, pretending to look for a porter. She heard the Russian talking hard to the passport officer, and through the corner of her eyes she saw him open the precious valise and take from it papers indicating that he was from the Russian Embassy in Berlin.

The passport officer looked duly impressed.

The man with the valise came over to Maud.

“The passport official and I are telegraphing the Foreign Office in St. Petersburg for permission for you to enter without my passport.”

The train was kept waiting an hour and the permission came.

Maud was overjoyed, but she soon discovered another difficulty that she had to attend to. The obliging official had reserved a special carriage for her and the man with the valise. He was on his knees before the train even left the station. “It is my great joy to meet such a beautiful and wonderful lady,” he said.

Maud had her revolver in her pocket, but the young man was far too sympathetic for her to imagine brandishing it.

“I, too, am happy to meet a Russian like you,” said Maud, taking him by the hands. “I feel a man such as yourself could understand an Irish girl. I have always believed that Russians were an understanding people, not at all like Englishmen or Frenchmen, who look upon women in a vulgar way. In my country women are very free because friendship between men and women can be beautiful and not commonplace.”

The appeal to his national honor was a success. He got up from his knees and though they still held hands, they talked of Ireland and of Russia quite happily.

“Why did you not give me such queer looks on the train?” Maud asked.

“In truth, mademoiselle, I thought you belonged to some foreign religious order, so I did not dare come into your compartment or speak to you.”

Maud remembered that she was wearing her black veil. “It does give me a rather ‘nun-like’ appearance,” Maud conceded with a laugh.

“We will be celebrating the nine hundredth anniversary of the introduction of Christianity to Russia this May,” said her sympathetic friend. “It should prove to be grande fête, well worth a visit, if, during the course of your travels, you find yourself in Kiev this summer.”[39]

ST. PETERSBURG

Princess Ekaterina Adamovna Radziwill.

In St. Petersburg Maud rendezvoused with Princess Ekaterina Adamovna Radziwill (Rzewuska) at the Hotel Hôtel de l’Europe where they both were staying. The Princess was an refined Polish woman who dabbled in politics. Maud and Radziwill took an immediate liking to one another. Through an introduction which Princess Radziwill procured for her, Maud handed the dossier were handed over to Pobedonostsev who put it under the eyes of the Tsar.

Konstantin Pobedonostsev.

The day after they arrived in St. Petersburg the Russian man from the train brought his wife to visit Maud at the hotel.[40] In his valise were the very papers from Count Shuvalov, Russian Ambassador to Berlin, of which Madame Adam had spoken. He never knew that the woman he helped gain entry to Russia had already delivered Madame Adam’s message into the hands Pobedonostsev. This marked the end of the League of Three Emperors and the beginning of a Franco-Russian alliance.[41]

Maud stayed another two weeks in St. Petersburg. In the parlors of Princess Radziwill, she met W.T. Stead, who was also staying at the Hôtel de l’Europe. Many friendly meetings were held, in which politics and society were freely discussed.[42] One evening began with a song from Madame Novikova, Stead’s friend who kept an apartment at 38 Troitsky Lane.[43]

“Madame Novikova sings well,” said Stead. “Her wonderful, resonant voice once delighted the poor inmates of Bedlam Asylum.”[44]

Novikova, a Theosophist, and friend of Blavatsky, then shared a story of Blavatsky’s phenomenon.[45] “I had been singing a Russian song that I had brought with me that evening, which seemed to give much pleasure to my audience,” said Novikova. “After the last chord of the accompaniment had died away, Madame Blavatsky said, ‘Listen!’ and held up her hand, and we distinctly heard the last full chord, composed of five notes, repeated in our midst. I have, of course, not the slightest means for giving any kind of explanation, but the facts were such as I have stated.”[46]

Madame Novikova.

Maud knew Madame Novikova lived for some time in England, and she heard her called a Russian spy when she stayed with Aunt Mary. She also heard Madame Blavatsky called a spy and had even been ordered to leave India. “It is because the English officials there could not understand that strange philosophical old woman,” Maud thought, “and the Indians did.” As for being a spy. “It did not mean much to be called a spy in England,” Maud reasoned, “the English get a spy mania every time they are afraid of another country, and the English were very much afraid of Russia, especially in regard to India.” Madame Novikova, though, might very well be a Russian spy.

Talk naturally turned to intrigue.

The British were two months into their invasion of Tibet, much to the consternation of St. Petersburg society. Russian political interest in Tibet was to a large extent generated by what they regarded as “sinister designs” on the country by its British adversary. The Indo-Tibetan border clashes clearly attested to British encroachments upon the neighboring country. Thwarting this British aggression seemed only natural from the Russian point of view.[47]

Nikolai Ivanovich Achinov.

Then there was talk of Abyssinia and Russia, and of Achinov. “The Russian intrigue which has threatened so long to molest Britain in their progress in Africa.” There had been much bowing and kissing of hands between Negus Yohannes IV and the Tsar, who, guided by Achinov had deemed it possible to establish Russian influence in Abyssinia. It was Achinov, after all, who persuaded the Negus to send the Tsar “a handsome present” which would also vex the English on the occasion of the 900th anniversary of the Russian Church. The Negus would send a gift “unique and unattainable to any other sovereign,” a solid gold cross “studded with jewels beyond all price,” that was venerated by the Greek Church. It was to be presented as part of the heritage of the Queen of Sheba (from whom the Negus proclaimed his descent.) This gift, however, concealed a religio-political motive. It was meant to symbolize a union between the Tewahedo Church (Church of Abyssinia) with that of the Russian Church, “both the Greek schismatics—from which it had hitherto been separated by the heresy of Eutyches admitting the exclusively divine nature of Christ and rejecting all belief in the human attributes of the Savior.”[48]

It was only when remarking about the Russian Orthodoxy that Stead offered his only negative critiques. “Pobedonostsev rages his orthodox zeal against the sectaries who dare to obey Christ in their own fashion,” said Stead, smiling at Maud. “Exile, imprisonment, punishment is meted out by him as by a second Caiaphas to all who oppose the most holy law and the orthodoxy which is the pillar and mainstay of the Russian State.”[49]

Novikova glared at Maud.

Stead tried to get a better grip on his podstakannik, the metal appendage which held his stakan (drinking glass.) It was a novel way of drinking tea, Stead thought, but not at all like the English way. “Tea,” said Stead, “even though it is served in glass here, is one feature in the Russian prison dietary which I hope will be introduced into English prisons when the next Royal Commission reports on the reforms necessary to improve the treatment of prisoners. The unspeakable charity and mercy of allowing the prisoners to procure tea every day if they care to pay for tea and sugar out of their earnings in jail. Only those who have known what it is to go on day after day with no vision of any beverage more inspiring than skilly can appreciate the enormous boon which this simple Russian rule would confer upon the English prisoner.”[50]

Princess Radziwill leaned into Maud. “I am very curious to know why, exactly, Mr. Stead is in Russia.”

“I will find out,” said Maud. “Stead,” she said, “what compelled you to travel to Russia? Are you working on a piece?”

“It is a peace mission of sorts,” said Stead. “I went to St. Petersburg and was received by Tsar Alexander,” said Stead, sipping his tea with some difficulty.[51] “There exists in London a widespread feeling of uneasiness and of anxiety as to the possible outbreak of war in Europe. The Continent is scared by an alleged concentration of Russian troops on the frontiers of Germany and Austria. Germany, in response, has enormously increased her armaments and Austria is preparing for war. Add to that the unrest caused by General Boulanger’s rise to notoriety in France, which seems to menace with convulsion the disturbed quasi-tranquility of the Continent. In military circles the talk is all of war. ‘General Boulanger is going to overthrow the Republic,’ they say, and then finding that he must do something to justify his ascendancy, it is gravely declared that he will probably attack England. London, with its incalculable wealth, ‘lay at the mercy of a daring adventurer.’ “Russia, it is added, is preparing to rush Constantinople under pretext of an expedition to reestablish her lost ascendancy in Bulgaria. The air is full of premonitions of the panic. The chief cause of this, no doubt, is the insufficiency of our armaments to stand the strain of serious war. In the public consciousness, it is also believed that Europe is entering upon a new era; the most conspicuous sign of which is the passing away of the men who had made the history of the last quarter of a century. The reign of Frederick, whose death bed was his only throne, marked the parting of the ways between the Old Europe and the New. Before the new Emperor came to the throne of Germany, I thought it desirable to endeavor to ascertain, as best I could by means of a personal visit to the three northern capitals, what the opinion was of those in whose hands lay the destinies of the future as to the prospects of peace.

W.T. Stead.

“It seemed especially important to visit St Petersburg in order to see the authorities who have it in their power either to keep the peace of Europe or to light up the flames of worldwide war. Whether for good or for evil, Russia holds in her hands the balance of power in Europe. The other states are either paralyzed by internal dissensions, or foreign vendettas and entangling alliances. Russia alone of the great military Powers is self-contained and self-sufficing, free alike from embarrassing alliances and paralyzing antagonisms. According to popular prejudice in England, the Tsar is the ‘great disturber of the peace’ in Europe and Asia. This is the root idea of the so-called traditional policy of the British Empire. The disturbing forces in the European situation are France and Russia. France, avowedly, is training for an attack on Germany. Russia is her natural ally. Russia, moreover, has designs of her own on the Balkan Peninsula and Constantinople, which render her of necessity a menace to the status quo.”

Maud found Stead to be “a man with puritanical beliefs constantly warring with a sensual temperament, which induced in him a sex obsession.” It seemed that he could talk of nothing else and inserted the topic into “every conversation, on whatever subject.” She told him as much later that evening.

“I find the subject rather repellent, Stead. I hate such talk.”

Stead looked embarrassed as they parted that evening. This scene led Stead to compose a “very amorous” (and less-than-wise) letter in which he endeavored to explain himself.

Maud, undecided as to whether she would respond, left Stead’s note in her writing-case on the table in her room.

St. Petersburg, Nevsky Prospekt.

The following day Maud spent the afternoon riding in a droshky (three-horse carriage) with an old Russian. He was once a great friend of her father’s when he was military attaché at the British Embassy in St. Petersburg. It was the old man’s way of honoring that friendship, and more pleasant memories of his youth. When Maud returned in the evening, she found Madame Novikova, whom she only casually met at the party, waiting for her in Radziwill’s parlor. Madame Novikova explained that she desired to get to know Maud. The talk was disappointingly boring, and after a very short time, Madame Novikova excused herself for another engagement.

Hotel l’Europe, St Petersburg.

Stead called on Maud the next morning in a state of great agitation.

“I have not slept all night,” said Stead. “I had to come and ask you how you could, you of all people have done such a cruel horrible thing.”

“Done what?” Maud asked, in astonishment.

“Laughed at my love for you with Madame Novikova,” said Stead. “You showed her my letter to you.”

“But you are raving, Stead,” Maud replied. “I hardly know Madame Novikova.”

“Don’t deny it, it makes it worse. She repeated the very words in that letter!”

Stead, an emotional man, buried his head in his arms on the table and cried.

Maud then remembered Novikova’s unexpected visit the previous day. She went to her writing-ease. The letter was there all right, but Madame Novikova must have opened the case and read it before she came in. Maud felt very angry, but seeing Stead so forlorn and crushed, she kept it to herself.

“You have nothing to complain of,” said Maud, laughingly, to soothe his vanity if not love. “You should he very happy! You have made a Russian conquest, much better for you than an Irish one, and the lady must love you very much. Isn’t jealousy a sign of love? My compliments.”

Stead smiled.

“I found Madame Novikova alone in my room last evening,” said Maud.

Madame Novikova was almost old enough to be Stead’s mother. Was there a political reason for Madame Novikova’s interest in Stead? She must have wanted to find out something very much to have resorted to such means. “She is obviously watching Stead,” thought Maud, “for she could have no political suspicion of such a butterfly as myself’ passing like a flash in the gay society of St. Petersburg.” Maud’s curiosity was aroused. She had to find out at once. Thinking Stead needed some refreshment after his emotional crisis, she rang the bell and ordered tea, for herself in a long glass with lemon, and for Stead à l’Anglaise with a teapot and a cup and milk (for she remembered his vain efforts to enjoy the tea in glasses.) Stead cheered up under the influence of his national beverage.

“It is possible that jealousy may be at the root of Madame Novikova’s strange behavior,” said Stead.

He then told Maud a story which Maud found deeply interesting.

“I have known Madame Novikova a long time,” said Stead. “I met her when I was a very young journalist on a provincial paper. She was the first cultivated, intelligent woman I had ever met. She recognized my talent and first made me believe in myself, and in the possibility of becoming, through my power of expression, a real power in the affairs of England. It was through her influence that I became editor of The Pall Mall Gazette. She wants to see English liberal ideas introduced into Russia and wants the Russian and the English people to become friends. We are working for a strong Anglo-Russian alliance.”

Maud could not let this happen.

“The scene with Madame Novikova the night before was very painful,” continued Stead. “She felt I had betrayed her by my too evident admiration for you and tried to turn me against you by saying that you had laughed at me with her and showed her my letter.”

Stead, despite being a husband and father, became Novikova’s lover. He ended the relationship when Stead’s wife discovered the affair. “I am still deeply attached to her,” Stead would say, “but I no longer love her with that sinful passion the memory of which covers me with loathing, remorse and humiliation…I love her intensely, but no longer as a second wife.”[52]

The reason for Novikova’s strange behavior was, in fact, because of jealousy, and not just over Maud. Novikova had a feeling that Annie Besant had developed feelings for Stead, after starting Link with him. Novikova told Blavatsky of her feelings, who responded with the following advice: “Your Stead is not one whom you’d call an ‘erotic genius.’ See that you don’t fall ‘into the well.’”[53]

All the while Besant was showing more and more affection toward Stead. “Like Diogenes,” Besant told Stead, “I have [been] looking for ‘a man’ for some time, and you seem to me the very one who has head & heart enough for the work.” Besant confided in him about her crisis of faith. She admitted her difficulty in believing in a righteous God that could permit the existence of so much evil. “The horror and the hopelessness of it all nearly drove me mad,” she told Stead. “I won my way into the peace of Atheism which leaves man without an Almighty Torturer while it leaves him also without a Father.” She told Stead that she longed to believe in his vision for “Church of the future,” what Stead called his “Civic Church,” and recover her lost faith in God. He was Besant’s “Sir Galahad,” and upon his spiritual advice, she read Carlyle’s Cromwell, works by Archbishop Manning, and attended sermons at St. Paul’s Cathedral. In late March 1888 Besant told Stead that “in a very real sense you are a messenger of God to me for good.” Weeks later Besant wrote another letter to Stead in which she confessed her love to him and said that she hoped he shared her feelings. But Stead had traveled to Russia without letting Besant know. She sent him a letter in which she expressed her disappointment of learning of his “movements first from a stranger.” Their joint projects of Link and the Law and Liberty League ended, and Besant kept busy by assisting with the matchgirl strike.[54]

“Well, perhaps she is right in trying to turn you against me,” said Maud, “and even lying for the purpose and opening other people’s letter-cases. I have only one interest in life and that is to free my country from yours. She is certainly right to tell you not to write such letters, and if you like you may tell her I say so. Now we will light cigarettes with this one.” Maud took a letter out of the letter case. “We will not talk about it anymore. In return for your story, I will tell you of the reasons why I hate your nation, though not individual English people, many of whom I like very much when I can forget they are English.” Maud told Stead about the evictions in Ireland to which he was very sympathetic.

“I know Michael Davitt,” said Stead, “I have a great admiration for him and his Land League activities. In his early life in an English factory, he had had his arm torn off in the machinery. He is a great man, far greater than Parnell. You must meet him.”

Stead would have stayed and chatted all night, but he had many farewells to make before traveling on to Yasnaya Polyana to meet Tolstoy. [55]

Maud decided she must warn Catherine that Madame Novikova was working for an English alliance and was responsible for Stead. So, she bade Stead farewell.

“I promise to help you if ever you need me,” said Stead.

Maude wanted to get to work for Ireland quickly. From what Stead had said, she thought Michael Davitt would be the best person to see.[56]

THE AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS:

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

VI. WITH LOW AND NEVER LIFTED HEAD.

VII. IMPERIAL GOTHIC.

VIII. THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN.

[APPENDICES]

A SWASTIKA WITHIN A CIRCLE.

THE ENGLISH IN INDIA I.

THE ENGLISH IN INDIA II.

THE ENGLISH IN INDIA III.

SOURCES:

[1] Old Harbor Vieux-Port, Marseille, France, with Hôtel-Dieu Hospital in background. , ca. 1890. [Between and Ca. 1900] Photograph.

[2] Old Harbor Vieux-Port, Marseille, France, with Hôtel-Dieu Hospital in background., ca. 1890. [Between and Ca. 1900] Photograph.

[3] “A Week with the Brigands of Smyrna.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England.) October 13, 1887.

[4] MacBride, Maud Gonne. A Servant of The Queen: Reminiscences. Victor Gollancz. London, England. (1938): Foreword.

[5] “Mr. Stanley’s Expedition.” The Daily News. (London, England.) November 28, 1887.

[6] “Miscellaneous Items.” The Brewer’s Guardian. Vol. XIX, No. 482 (April 2, 1889): 108.

[7] MacBride, Maud Gonne. A Servant of The Queen: Reminiscences. Victor Gollancz. London, England. (1938): 88.

[8] Hunter, F. Robert. Egypt Under the Khedives, 1805-1879: From Household Government to Modern Bureaucracy. American University in Cairo Press. Cairo, Egypt (2000): 14-16; Mestyan, Adam. Arab Patriotism: The Ideology and Culture of Power in Late Ottoman Egypt. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (2017): 115-118.

[9] Mestyan, Adam. Arab Patriotism: The Ideology and Culture of Power in Late Ottoman Egypt. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (2017): 14-15, 86, 115-118.

[10] Many competing legends regarding the construction of the pyramids was the prevailing concern of medieval Egypto-Arabic literature. One such mystery was whether the pyramids were built before or after the Noachian deluge. By the ninth-century the two strongest traditions were those of the traditionalists, and the Hermeticists. The traditionalists believed Egyptian civilization began after the Flood, by Noah’s grandson, and centered on the biblical personalities of Abraham, Joseph, and Moses. Hermetic history, however, believed there were lost antediluvian civilizations with cultures that possessed magical technology, amulets, priestly astrologers, philosopher-kings, ancient wisdom, and astonishing feats of engineering. The scholastic tradition of these Medieval Arabic Hermeticists articulated a tradition which spoke of three ancient figures by the name of Hermes, which formed the basis for “Hermes Trismegistus.” The first Hermes was associated with Idris (the Biblical Enoch) who, learned of, and mastered, the astrological sciences from his grandfather, Ādam (Adam.) He was said to have been the first person to have predicted the Flood. He was responsible for the construction of these temples and pyramids and engraved their walls with the secrets of the sacred sciences, to survive the prophesied deluge. The second Hermes was a Chaldean philosopher who recovered the lost knowledge after the Flood, while the third Hermes was a physician who roamed Egypt, transcribing texts. [Stolzenberg, Daniel. Egyptian Œdipus: Athanasius Kircher and The Secrets of Antiquity. University Of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. (2013): 155-158.]

[11] Holt, P.M. The Mahdist State in the Sudan 1881–1898: A Study of Its Origin, Development, and Overthrow. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1958): 32-44.

[12] Searcy, Kim. The Formation of The Sudanese Mahdist State. Brill. Boston, Massachusetts. (2011): 53.

[13] Griscom, Lloyd C. Diplomatically Speaking. The Literary Guild of America. New York, New York. (1940): 129-141.

[14] Garnett, Lucy Mary Jane Garnett. Turkish Life in Town and Country. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1904): 106.

[15] Cox, William Van Zandt; Northrup, Milton Harlow. Life of Samuel Sullivan Cox. M.H. Northrup. Syracuse, New York. (1899): 138-146.

[16] Griscom, Lloyd C. Diplomatically Speaking. The Literary Guild of America. New York, New York. (1940): 129-141.

[17] Stone, George M. “Constantinople and Its Great Mosque.” Worthington’s Magazine. Vol. III, No. 5 (May 1894): 451-467.

[18] Straus, Oscar Solomon. Under Four Administrations. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1922): 96.

[19] “The Progress of The World.” The American Review of Reviews. Vol. XXIII, No. 1. (January 1901): 3-23; Van Norman, Louis E. “Ambassador Straus, The Man for the Emergency in Turkey.” The American Review of Reviews. Vol. XXXIX, No. 6. (June 1909): 685-688.

[20] Johnston, Charles. “The New Secretary of Commerce and Labor.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. L, No. 2604. (November 17, 1906): 1647, 1651.

[21] Griscom, Lloyd C. Diplomatically Speaking. The Literary Guild of America. New York, New York. (1940): 136.

[22] [Arrived November 28, 1887] “Baron Hirsch at Constantinople.” The Nottingham Evening Post. (Nottingham, England.) November 29, 1887.

[23] Straus, Oscar Solomon. Under Four Administrations. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1922): 93.

[24] Ibid. 92-96.

[25] Ibid. 62.

[26] “Germany and Russia.” The London Evening Standard. (London, England.) September 20, 1887.

[27] “Germany and Russia: Alleged Extraordinary Forgeries.” The Gloucestershire Echo. (Gloucester, England.) November 25, 1887.

[28] Radziwill, Catherine. My Recollections. Isbister & Company. London, England. (1904): 286.

[29] “Germany and Russia.” The London Evening Standard. (London, England.) December 3, 1887.

[30] Edwards, Henry Sutherland. Sir William White, For Six Years Ambassador at Constantinople: His Life and Correspondence. John Murray. London, England. (1902): 245.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Leroy-Beaulieu, Anatole. The Empire of the Tsars and the Russians. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1893): 97-99.

[33] Radulovic, Nemanja. “Slavia Esoterica Between East and West.” Ricerche Slavistiche. Vol. XIII, No. 59. (2015): 73-102.

[34] Edwards, Henry Sutherland. Sir William White, For Six Years Ambassador at Constantinople: His Life and Correspondence. John Murray. London, England. (1902): 244.

[35] “Foreign.” John Bull. (London, England) December 3, 1887.

[36] “London Gossip.” The Birmingham Daily Post. (Birmingham, England) August 24, 1888; “An Abyssinian ‘Moscow.’” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) February 27, 1889; Lloyd, Olga Amarie; Lloyd, Rosemary. Juliette Adam. The Lilly Library. Bloomington, Indiana. (2007): 40-47.

[37] Radziwill, Catherine. My Recollections. Isbister & Company. London, England. (1904): 286-287.

[38] Adam, Juliette; Percy, John Otway (tr.) The Schemes of the Kaiser. William Heinemann. London, England. (1917): 27.

[39] Stead, William T. The Truth About Russia. Cassell & Company, Limited. London, England. (1888): 330.

[40] Kennan, George F. “Franco-Russian Relations, 1879-1880.” In The Decline of Bismarck’s European Order: Franco-Russian Relations 1875-1890. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (1979): 40-59.

[41] Radziwill, Catherine. My Recollections. Isbister & Company. London, England. (1904): 286-287.

[42] Ibid.

[43] V.P. Zhelihovsky to A.S. Suvorin. St. Petersburg, Russia. February 1888. “The Letters of V.P. Zhelihovsky.” The Bakhmut Roerich Society.

[44] Stead, William T. “Character Sketch: Madame Olga Novikoff.” The Review of Reviews. Vol. III, No. 14. (February 1891): 123-136.