You can never know Dorchester well enough, especially on deadline.

Ed Forry learned that lesson again, on his tenth time as publisher and editor of the Dorchester Day supplement to the weekly Dorchester Argus-Citizen. The year was 1983, and the insert’s red-white-and-black cover saluted a high point of the preceding twelve months with a lead photo of President Ronald Reagan hoisting a one-dollar mug of Ballantine Ale in Adams Village. A forgettable photo op for the rest of the country, it made, for all its contrivance, a historic splash in Dorchester.

The only problem was the headline just above the photo. It was supposed to say A Presidential Toast at The Eire Pub. But, instead, the pub’s locally familiar name was misspelled, as in the name of a canal or Great Lake.

If not a lack of knowledge, the gaffe betrayed journalistic haste, or maybe the speech habits of Boston, where Eire – the Irish word for Ireland – commonly, but erroneously, rhymes with “eerie.” By the time the front-page typo was flagged, the supplement had already sped through the printing presses downstairs, in the basement of the Harwich Lithograph plant in Hyde Park.

A lifelong resident of Dorchester, and proud of his Irish heritage, Forry acted as if he should have known better. He asked for all copies of the supplement with the tainted cover headline to be thrown out, and he offered to pay for a new printing run, with the corrected spelling. “If it were buried inside or something, it’s one thing” he recalled telling a plant manager. “I can’t live with that. I’ll be a laughingstock.”

Four decades later, Forry looks back on the correction as “one of the great moments.” He and his wife, the late Mary Casey Forry, took charge of the supplement in 1974, one year after it had been started by the Harwich weekly newspaper chain. With a roundup of news highlights from the previous twelve months and a scattering of photos (many without captions), the supplement was a way to sell more advertising while sporting the neighborhood brand in a display of community spirit, just in time for the annual celebration of Dorchester Day.

Reporter co-founders Mary Casey Forry and Ed Forry.

In his first try as editor, and determined to produce something better, Forry christened the supplement a “Dorchester Yearbook.” By the fall of 1983, the Forrys would take their experience and commitment to another level, by starting what would become their own weekly paper, currently known as the Dorchester Reporter. But the supplement had its own lifespan and mission, inspiring Dorchester Day sections in the new weekly, but also as the yearbook that aged into a time capsule.

•••

Long before his career in community journalism, Ed Forry had to learn that Dorchester went far beyond the range of family, friends, and schoolmates. Even with a declining US Census count in 1970, the total for tracts in Dorchester –including Mattapan – outnumbered the populations of every city in the state outside of Boston.

While growing up, he mapped himself in his surrounding neighborhood, Codman Hill, and St. Gregory’s Parish, based in Lower Mills. “You didn’t think of yourself as from Dorchester,” he recalled. “You thought of yourself as from a parish or, even more minutely, from a neighborhood within the parish.”

That changed when Forry was still a student at Boston College and working part of the year as a US Post Office letter-carrier. He covered ground from Lower Mills and Adams Village to predominantly Jewish neighborhoods near Blue Hill Avenue, from the border of Mattapan around Morton Street to addresses within a few blocks of Grove Hall. As a result, a world divided into smaller parts began to look like a larger whole.

“I became very familiar with Dorchester as a collection of very similar neighborhoods that didn’t need to be divided and shouldn’t be divided,” he said. “They should be thought of as one.”

In 1965, Forry also took to the streets when he cut classes to join the march from Roxbury to Boston Common led by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. The purpose of the event and the civil rights leader’s address to the state Legislature was to highlight another divide – racial inequality in northern cities, whether in schools, housing, or employment. In Boston, the divide was already being challenged by leaders of the Black community, who met strong resistance from political leaders and voters who were overwhelmingly white.

Forry made his first contribution to the supplement in 1973, after he started working for the Argus-Citizen as a regular columnist—in addition to his full-time work for the local anti-poverty agency, Action for Boston Community Development (ABCD). And he was covering more neighborhood territory by volunteering to handle media relations for the Dorchester Day Celebrations Committee. By this time, Boston’s racial divide was even more in the forefront, and Black parents had already filed a lawsuit in federal court that would result in a school desegregation ruling the following year.

Even before the ruling, the demographic flux in Dorchester and adjacent neighborhoods was accelerating. A mortgage program, introduced in 1968 to remedy racial inequality in access to home ownership, replaced the boundaries of discriminatory “redlining” with new boundaries. But the map that was supposed to help Black homebuyers led to racial steering and blockbusting. Within a few years, parts of Dorchester had a rash of foreclosed mortgages, with abandoned houses often giving way to vacant lots.

In his piece for the 1973 supplement, Forry touched on the “pressures of urban neighborhood life,” which could take many forms, from declining attendance at church to a fire at a bowling alley, or a corner store that was no longer open at night.

“A robbery occurs in the shopping area 12 blocks away, and you feel a collective fear because that’s where you and the kids were shopping just yesterday,” he wrote. “Someone tries to sell a house, and word comes that there were no offers to buy at his price, and there were no mortgages available when the buyer did come around.”

By June of 1976, the yearbook took notice of the conflict over the remedies for school segregation imposed by federal court, under Judge W. Arthur Garrity. In his commentary, Forry denounced the loss of access to neighborhood schools, and the lack of voluntary desegregation options, as an “unjust demand” on Boston’s white parents.

“One third of them have taken the painful method of protest which at least allows them their reputations,” he wrote. “They have left the system.” As the US Census would later confirm, they also left the city: between 1970 and 1980, Dorchester’s white population would go from almost 70 percent to less than 50 percent, while its Black population would go from less than 20 percent to more than 40 percent.

The look of change was also apparent in many of the 1976 yearbook’s photos, many contributed by Eugene Richards, a Dorchester native who was still on his way to becoming an acclaimed photographer. His first book, published three years earlier, drew on his experience as a VISTA volunteer and activist in the Arkansas Delta region, an area afflicted with poverty and racist violence. In 1972, he was back in Boston and taking photographs in his old but very changed neighborhood.

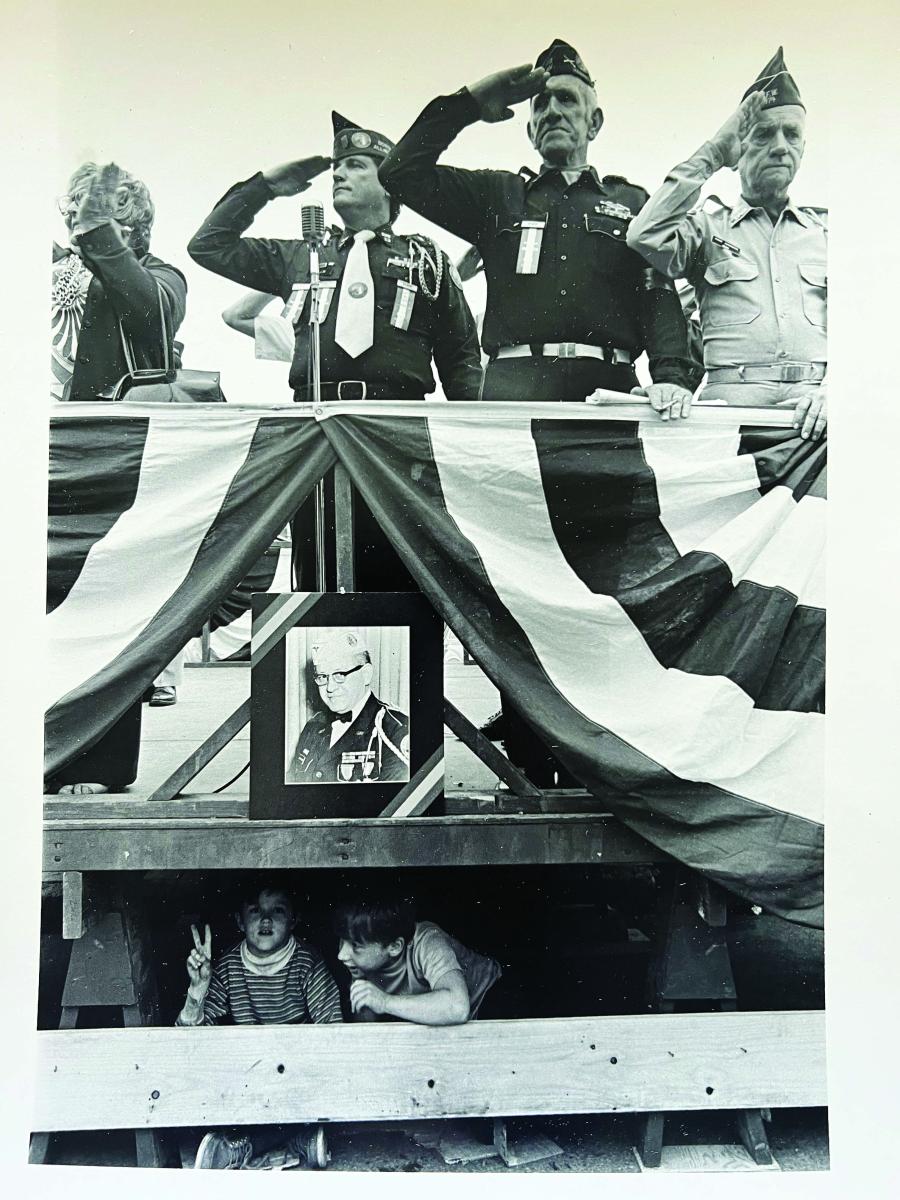

An iconic photo by Eugene Richards graced the 1976 cover of the Forrys’ Dorchester yearbook.

In the yearbook, the Richards contribution begins with a full-sized cover photo. The upper tier shows a platform with three uniformed veterans in ramrod salute, a middle tier with the photo of a deceased veteran flanked by patriotic bunting, and a lower tier, with two boys peering out from the shadow beneath the platform, one of them flashing a peace sign.

With its mix of ceremony and innocence, the photo makes for a composite: How Dorchester presents itself, how it’s remembered, and how it is. On Page 20 of the yearbook, there’s a group of Richards’s photos surrounding text by his partner and creative collaborator (and also a Dorchester native), the late Dorothea Lynch. The people in the photos are diverse racially, but also in other ways: the uniformed police officer with two kids decked out for a bicycle decoration contest, the girls in bathing suits over the street-wide gush of a hydrant, the befreckled princess in her first communion gown. After she’s taunted by three boys on bikes, the yearbook shot has her sticking out her tongue –almost like a rogue shot in a family album.

Richards published a larger group of photos in his 1978 book Dorchester Days, but in 1976 he was struggling to get his work to a larger public. “This was not the work that would go to galleries and whatever,” he said. “That’s why, when you talk about Ed Forry, it was probably pretty unusual that anybody cared to publish pictures like that, or certainly about Dorchester.” Nor did it hurt that, as Richards put it, Forry was a “very open and welcoming presence.”

Richards acknowledged that some people found the photos in Dorchester Days edgy and even coarse. But some of the images reappeared at a renovated Ashmont Station in the 1980s, in a display that was, as he noted with pride, unmarred by vandalism.

•••

During the yearbook decade, Dorchester, like the rest of Boston, was caught in an epochal switch from a declining industrial port to the burgeoning hub of a knowledge economy. Thanks to help from federally backed highways and mortgages, more and more of the Boston area’s best paid workers would commute from single-family homes in the suburbs. That meant the onetime “streetcar suburbs” such as Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan, would be left behind. In contrast with the new outposts, the old neighborhoods were defined by a cramped inventory of aging three-deckers, many contaminated with lead paint.

In the fall of 1976, the neighborhood brand suffered again when Dorchester Savings Bank, one of the state’s largest thrifts, announced that it would change its name to “1st American Bank for Savings.” Some of the negative local reaction would be registered in Forry’s column for the Harwich chain. But, within a month, he was offered a job at the bank as its director of community relations.

Shortly after he came on board, the bank changed its tone – and the storyline – by rolling out “The First Fund for Dorchester’s Future,” which committed $1 million for home mortgages. Within less than a year, according to The Boston Globe, the bank’s new investment in Dorchester would be almost $4 million. By the time of the 1979 yearbook, a full-page ad by 1st American would boast of helping more than 700 families buy homes in Dorchester over the previous 24 months.

When the fund was introduced, there were doubts that it would succeed. Forry recalls the cool reception for the program after the bank’s president, Arthur F. Shaw, picked him up in his Lincoln Continental and drove to a meeting at St. Ambrose School Hall near Fields Corner.

“And,” said Forry, “the feedback was this: It’s very nice that you want to lend us money, but the problem is, nobody wants to buy these houses. Nobody wants to buy in Fields Corner.”

The next step was to combine the capital with courses and other events that would help buyers take on the challenge of ownership – as well as see the advantages of living and investing in Dorchester. It was a strategy that Forry said would evolve on a larger scale under the federal Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, which would require lenders to plow some of their earnings back to their base communities.

One participant in a “First Fund Forum” who also contributed articles to the supplement about housing in Dorchester was Bob Rugo. A recent arrival who grew up in Milton, Rugo was a planner at the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA). In 1975, he and his future wife, Vicki Kayser, bought their first home, a three-decker on Walton Street.

“We put in a sealed bid at $14,100, and we couldn’t get financing,” said Rugo, “so Vicki and I each put in $7,000.” They also had to contend with a legacy of lead paint, but that didn’t stop Rugo from highlighting Dorchester’s old houses as worthy of preservation. The Rugos still live in the Ashmont Hill neighborhood, in the same house since 1983.

In addition to his articles for the supplement, the city was producing research and creating posters that celebrated Boston’s multi-family homes, not as look-alike containers, but as something more singular, with design features lending a touch of stately or rustic charm.

Citing one of the photos on the Dorchester housing poster, Rugo said, “You could see this eye-catching series of three-deckers going down to the water. And the other factor was economic: they were ridiculously cheap at the time.”

That message was spelled out in a yearbook ad placed by the administration of Mayor Kevin H. White, touting three-deckers as the “affordable Victorians.” By 1979, a vintage single-family at the corner of Percival and Bowdoin streets would become the first star of the popular PBS makeover series, This Old House—which made for another item in the yearbook. Another piece in the same edition hailed the transformation of a former garbage dump on the Columbia Point Peninsula into the waterfront mecca of the JFK Library.

What was good for the community was also good for a bank or a mayor seeking his fourth term in 1979. The same mindset came into play when Forry quickly organized the bank’s fund in response to the fire that destroyed the St. William’s Spanish Mission-style church in 1980.

Spreading word about the fund on local media outlets raised the bank’s profile and helped the parish. Decades later, that approach would become known as “creating community,” but Forry summed it up as a business ethic.

“The whole premise of what became our Community Reinvestment Act policy was: Act like you live here,” he said. “Act as if the future of this neighborhood is important to the future of the bank, or the future of this bank is important to the future of this neighborhood. It’s intertwined.”

•••

In one of his Dorchester Days images, Richards presents another composite, outside the S.S. Kresge department store on Dudley Street in Uphams Corner. In a store window to the left, an ad displays the groomed likeness of a white toddler in a gilt-framed portrait, tagged with a prize ribbon at 38 cents. On the other side of the photo, a few years older and bounding from shadow into light, a Black boy grips the reins of a coin-fed galloping pony—at 10 cents a ride.

Richards called the mechanical pony “a touch of romance and cowboy ethic in the middle of town,” a throwback to the TV westerns of his childhood and a fantasy of hopping one of the freight trains that passed over Dudley Street. And the rider outside Kresge’s, said Richards, was in a world of his own.

“Part of growing up in the inner city,” he added, “is your imagination. I don’t think anybody who grows up in the inner city doesn’t want to leave it in some capacity.”

That actually happened with another rider from Dorchester, Chris McCarron, who grew up five blocks from Ashmont Station. At 5-foot-3, with a barely passing grade average, he went straight from high school to Suffolk Downs. By age 22, he was a high-earning jockey in California and, eventually, a thoroughbred horse racing Hall of Famer. His story was told in one of the sports features contributed to editions of the yearbook by Paul Kenney, a local resident at the time who made his own try for the finish line in the Boston Marathon.

Another figure written about in the yearbooks who grew up in Dorchester was Ray Bolger. Renowned as the scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz, he was also choreographed by George Balanchine in the stage version of Slaughter on Tenth Avenue.

Some of the local figures who went on to fame – in places beyond Dorchester – told their own stories. Dick Sinnott, a newspaper reporter who became Boston’s “city censor,” did a roll call of neighborhood gangs, with turf names like the Chickatawbut Indians, the Greyhounds, the Wildcats, and the Dorgan Club—some of whose members joined the US Marines as a group after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

A longtime newscaster on Boston’s Channel 5, Jack Hynes, wrote about his own presidential encounter. When he was a student there, he was let out of St. Gregory’s School for a “fleeting glimpse” of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in Mattapan Square. Hynes recalled the names of people from the neighborhood who went off to war and never returned, as well as others who left for destinations in Braintree, Hingham, Needham and Westwood.

Forry wrote about his own glimpse of Pope John Paul II driving into Dorchester at Kosciuzko Circle. A photo in the 1980 yearbook, taken from a window on Dudley Street almost right opposite Kresge’s, shows the pontiff in a cape, raising his right hand. Behind him, perched on two different cars, are seven acolytes in trench coats and neckties and, further back, the composite face of Dorchester, crowding the corner of Columbia Road and Dudley Street, with some onlookers still waving back.

Forry might have relished the wording of the full-page ad placed in the 1979 supplement by The Boston Globe: “Dorchester is a great town. And it’s our town.” But even the city’s largest daily would relocate, printing its last issue in Dorchester 38 years later. By then, many of the local banks that could have been counted on for ads in the yearbook no longer existed, including 1st American and the largest, The First National Bank of Boston.

After enough time, some of the yearbook ads look like a directory of vanished businesses and institutions: Delaney’s Columbia Pontiac, St. Margaret’s Hospital for Women, even Gerard’s Sandwich and Ice Cream Shoppe and General Store, famed as the backdrop for political rallies in Adams Village. But, forty-five years after its ad in the 1978 supplement, the Ice Creamsmith is still doing business in Dorchester Lower Mills.

And it was the ads by political figures that most resembled the pages of a school yearbook. The faces of congressmen, state legislators, and city councillors are almost all white men in jackets and ties. Forty-plus years later, some of the faces, even if recognized, look unexpectedly young.

•••

The cyclical nature of the yearbook made it easier to branch off a timeline of events and convey something about the community’s atmosphere or texture. The 1978 issue included Mary Casey Forry’s diary about life in the week of the “Great Blizzard,” complete with a relative showing up at her family’s home in Lower Mills on horseback. Some issues listed Dorchester’s “favorite things,” such as dining and dancing at union halls, house tours, or the tables packed with two floors of bingo players at Ronan Hall, across from St. Peter’s Church.

Ed Forry observed that, even as he was putting supplements together, he imagined each of them as a snapshot that would be looked at in a distant future.

“I was very much conscious of that,” he said, “thinking of it as, not just reporting about that year, but something that you could look back on, because reading all the histories of Dorchester, to me, was fascinating.”

One other figure who shared that fascination was Rev. James K. Allen, an Idaho native who came to Dorchester after receiving a degree in theology at Boston University. In 1954, he become the minister of First Parish Church on Meeting House Hill, the oldest congregation in all of Boston, formed by Dorchester’s first English settlers in 1630.

In 1980, coinciding with the 350th anniversary of the church and the settlement, the yearbook highlighted the milestone and Rev. Allen’s discovery of what he believed were two missing pages from the handwritten final draft of the Declaration of Independence.

The pages were brought to Rev. Allen’s attention in 1976 by a Dorchester man, George Berg, who reportedly found them in a pile of newspapers predating the Civil War. According to The Boston Globe, Berg’s family ran a moving business and probably set aside the pile 50 years earlier, while clearing out one of Dorchester’s old mansions. Rev. Allen even conjectured that the pages might have once found their way to a US senator from Dorchester, Edward Everett.

Just as two Secret Service agents from Dorchester could guide Ronald Reagan to the Eire Pub, there could have been, as Rev. Allen surmised, a thread running from Thomas Jefferson to someone from a Dorchester mansion who might have played music with him. Or did it matter more that some of the wording in the Declaration echoed the ardent support for independence that was formally pledged at a Dorchester Town Meeting?

If 1976 was a time of conflict, marking an end to one kind of life and the beginning of another, the same could apply to 1776, or even 1630. After all, as The Globe noted, the two pages of the Declaration had been found underneath a newspaper dated June 11, 1853. And a look at that day’s edition of The Boston Evening Transcript would have turned up a review describing a new volume about Dorchester’s early history.

As updated in the 1980 yearbook, Rev. Allen was steadfast in his belief that the pages were an original in Jefferson’s handwriting, though he was still trying without success to have that certified or disproved by experts. Despite the uncertainty, Forry gave the story prominence, even reproducing the two pages in a centerfold with a red background.

If nothing else, Rev. Allen showed that Dorchester history was a layered composite. As they appeared in the centerfold, the pages had the jagged edges of something that looked old and maybe fragile enough to disintegrate. Instead of typeset characters in straight lines, this Declaration of Independence was a cramped scrawl, with some words crossed out, others crammed between lines, or dangling over the margin. If it was monumental enough to be history, it was also a kind of snapshot, a signature of the moment – like news copy needing a watchful editor to check for typos.

(Chris Lovett is a former news director at BNN News and news editor for the Dorchester Argus-Citizen. He was a contributor who helped with production of the yearbook from 1977-83.)