In the wilderness of New Hampshire within miles of his home, John Stark, a young frontiersman in the 1700s, was taken captive by a party of Native Americans. He was with three friends, one of whom was killed and scalped. His older brother, William, managed to escape thanks to some quick maneuvering, but John and Amos Eastman, the fourth member of the party, were taken captive.

It all happened at the end of a trapping trip as the foursome packed their canoes for the journey home. The Abenaki tribe, allies with the French, took captives whenever they could and sold most of them in Canada as servants or in exchange for French goods.

On the journey north with the Abenaki, Stark began to make the best of the situation and learn what he could from his captors. For example, when his friend Eastman was forced to run the gauntlet with only a thin pole to defend himself, he took a brutal beating. When it was Stark’s turn, he did the unexpected. He headed straight at one line of braves, yelling “I’ll kiss all your women.” His attackers were caught off guard, and Stark continued his attack even when his pole broke. It was an act of bravery that his captors respected. Legend also tells us that when Eastman and Stark reached the Indian village of St. Francis, the Abenaki ordered Stark to hoe corn with the women. Stark, understanding the humiliation intended, dug up the corn and left the weeds. He pronounced it “the business of squaws” and threw his hoe in the river. His action won him new respect. In time, he was included in the Abenaki hunting parties and invited into their cabins. Some say he was adopted into the tribe.

In July 1752, Phineas Stevens, commander of Fort Number Four on the Connecticut River, came north to ransom Massachusetts captives. When he found the New Hampshire men, he decided to expand his mission—and he made the Abenaki an offer they couldn’t refuse. “You’ll be pleased to know,” Stevens reportedly told Stark later, “that you’re worth the price of an Indian pony” (103 Spanish dollars). History would prove this was money well spent.

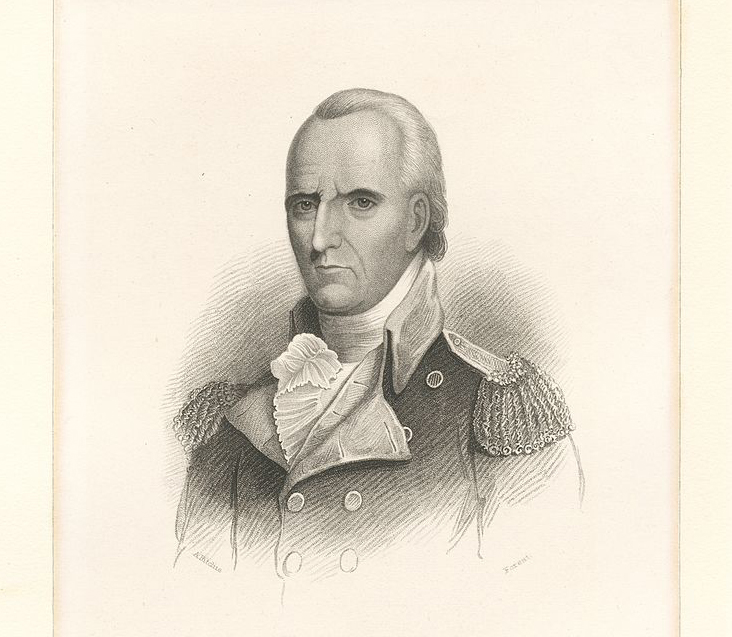

A Skilled Commander

Because of what Stark had learned about ambush fighting from the Abenaki, he was asked to join the legendary Roger’s Rangers, one of the most effective frontier military groups during the French and Indian War. Ranger fighting was indeed a new type of warfare, one which the English considered beneath their dignity.

When the French and Indian War ended, Stark married Elizabeth “Molly” Page, daughter of the first postmaster of New Hampshire, and settled into life as a family man (ultimately becoming the father of 11 children). He built a sawmill, launched a successful timber business, and increased his land holdings. He also kept an eye on the political scene. During the uproar of the Stamp Act, his brother, William, remained loyal to the Crown, but Stark did not. With the Boston Massacre, the closing of the Port of Boston, and the Boston Tea Party, Stark—a once-loyal British subject desiring compromise—became a member of the Sons of Liberty, promoting independence. Soon, he was recruiting local militia.

It was at the Battle of Bunker Hill that Stark and his men first distinguished themselves. A rail fence on the left side of the hill was key to the American defense, but only a few men were defending it. Stark spotted the weakness and had the fence fortified with hay, brush, and mud. Then, he ordered 200 of his men to build a crude stone wall to extend the barricade down to the water. Hammering stakes in the ground about 150 feet in front of the wall, he gave the order not to fire until the British reached the stakes. Stark had learned how to maintain almost continuous fire during his years as a ranger. The front line of militia would fire, then drop back to reload while the second line moved forward and fired, then the third, and back to the first. The first British regiment to reach the wall was decimated—and then another, and yet another. Officers were the main targets, soon leaving several companies leaderless and ineffective. Only a shortage of gunpowder forced Stark’s militiamen to retreat (in orderly fashion) and let the British claim the hill. But as Gen. Nathanael Greene later said, “I wish we could sell them another hill at the same price.”

Stark was there for the rest of the Boston action and for the British evacuation. After this initial success, however, things didn’t go well for the American cause. Stark continued to serve in prominent battles and was one of the ablest commanders, but his bluntness tended to offend prominent members of Congress. Officers with more political polish and less battlefield knowledge were continually promoted over him. Finally, in March 1777, he had enough. He resigned his commission and went back to his sawmill in New Hampshire.

New Hampshire’s Contribution

To those who tried to talk Stark into staying in the militia, he said only that the next major threat would come from the British in Canada, and he would be available if needed. He was right. By mid-June, British Gen. John Burgoyne and some 10,000 troops were on the march south from Lake Champlain to capture Fort Ticonderoga and overrun Vermont and New Hampshire. They planned to join up with British forces moving north from New York and the Mohawk Valley, and to cut off the New England colonies from inland support.

The Vermont Council of Safety appealed to New Hampshire for help, as did Col. Seth Warner of Vermont’s Green Mountain Boys. But New Hampshire had no troops, no money, and no credit. Fortunately, John Langdon, a Portsmouth merchant and speaker of the New Hampshire Assembly, took charge, saying:

I have three thousand dollars in hard money; my plate [meaning silver] I will pledge for as much more. I have seventy hogsheads of Tobago rum, which shall be sold for the most they will bring. These are at the service of the State. If we succeed, I shall be remunerated; if not, they will be of no use to me. We can raise a brigade; and our friend [John] Stark, who so nobly sustained the honor of our armies at Bunker Hill, may safely be entrusted with the command, and we will check Burgoyne.

Thus, it was settled. Stark agreed to take command as a brigadier general, on condition that he was accountable to no one but the New Hampshire Assembly and Committee of Safety.

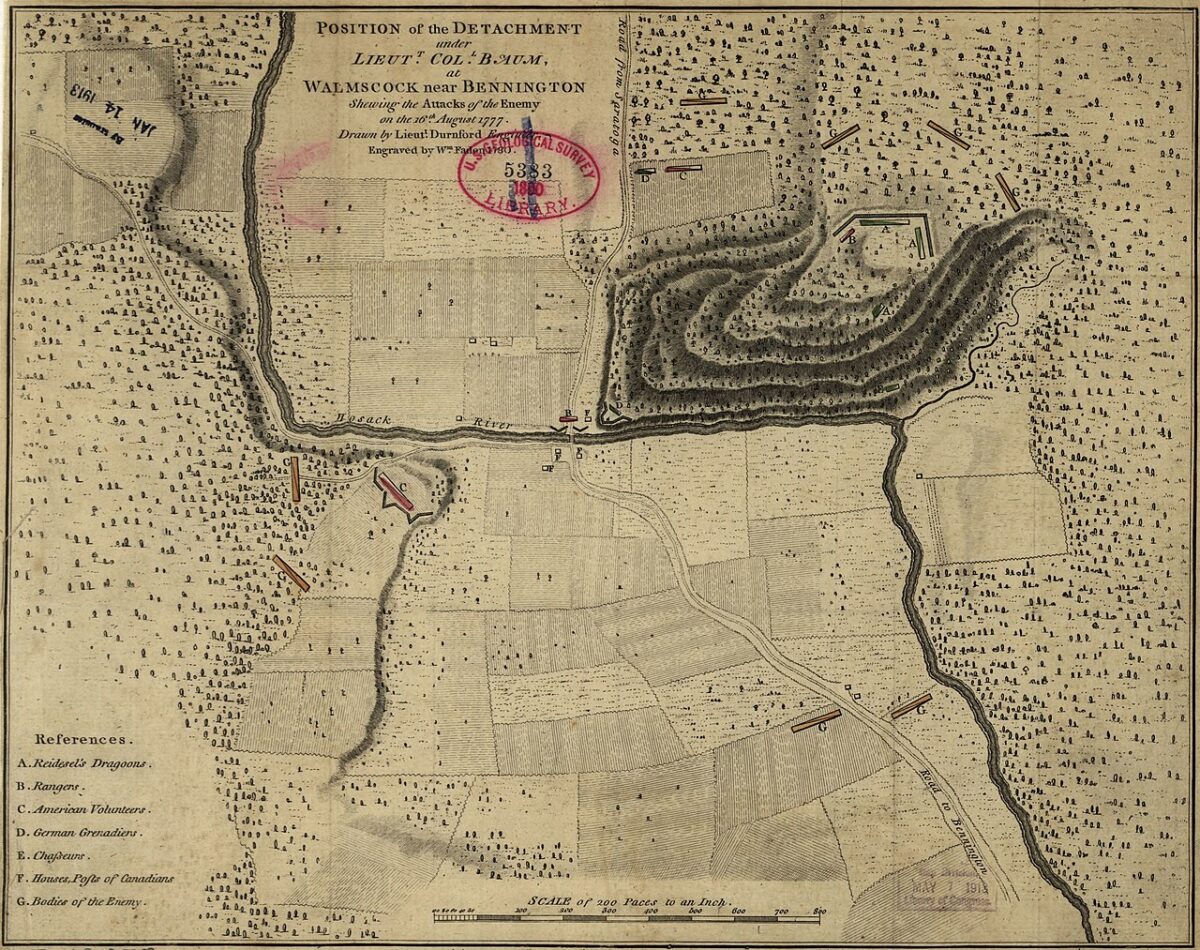

There was no lack of recruits. In six days, more than 1,400 enlisted. In many towns, one out of every ten men signed up. In Vermont, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, a political appointee with limited military experience, tried to redirect Stark and his brigade. Fortunately, Stark would have none of it. He was accountable to no one but the New Hampshire Assembly, and when he learned that Burgoyne had sent a mercenary troop of Hessians to Bennington, Vermont, to seek food and supplies, he sent word to Seth Warner and other militia men to meet in Bennington. Together, they formulated a workable battle plan. Stark reportedly gathered his men together and issued his famous call to action: “My men, yonder are the Hessians. They were bought for seven pounds and ten pence a man. Are you worth more? Prove it! Tonight, the American flag floats from yonder hill, or Molly Stark sleeps a widow!”

The Battle of Bennington went to the Americans. A short time later at Saratoga, after successive defeats at the hands of superior American forces, the British were backtracking to Canada when Stark reappeared at the right time and in the right place to close a critical gap and prevent Burgoyne from escaping. The British general ultimately was forced to surrender and return to England. It was an amazing victory for the Americans. It proved that professional soldiers could be beaten, and it signaled to European onlookers that the American rebellion was more than a feeble insurrection.

Live Free or Die

Congress promoted Stark to brigadier general, and he continued to serve during many difficult assignments as a trusted general under George Washington’s command. In 1783, his extraordinary service was finally recognized, and he was promoted to major general. What accounted for John Stark’s amazing success as a leader? Howard Parker Moore’s description of Stark gives some clues. The author says:

His troops knew his worth. They would follow him anywhere. They identified with him, loving his candor and common sense and homespun informality. He was their own kind, and they flocked to him when they gave only grudging support to others. In the end it was their devotion that persuaded the establishment to accept him too.

In 1809, Stark was asked by the citizens of Bennington to attend a celebration of the Battle of Bennington. Now 81, he declined because of his physical infirmities but sent this message:

You wish my sentiments. These you shall have, as free as the air we breathe. As I was then, I am now, the friend of the equal rights of men, of representative Democracy, of Republicanism, and the Declaration of Independence, the great charter of our National rights. …

P.S. I will give you my volunteer toast. Live Free or Die. Death is not the greatest of evils.

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.