THE DWELLER ON THE THRESHOLD

IX.

A heavy downpour of rain two nights earlier caused considerable damage in London. The weather over the British Isles appeared to be falling gradually into an unsettled condition again. Solar halos were seen all over the country and thunder hid in the oily clouds. Rain was a surety in the westward veering wind.[1] It came as a surprise, therefore, when Blavatsky agreed to Russell’s offer of taking her to get photographed at Vander Weyde’s studio on Regent Street. The day was open. Vera Petrovna was going to the Tower of London with Nikolas Notovitch, “the strange Russian,” with a “face like an icon,” according to Russell.[2] Verochka was preparing herself for the theatre that evening. Mabel Collins, who was undergoing an operation, gave her opening night ticket of the Lyceum’s production of Jekyll & Hyde to Blavatsky’s niece.[3]

Before everyone went their separate ways, they sat at the table discussing the events of the day. Conversation was about Achinov, the man largely responsible for convincing the Negus of Abyssinia to gift the Queen of Sheba’s cross to the Tsar, a man not altogether unlike the Vera Petrovna’s cicerone for the day. The press described Achinov as a “personage something after the type of the redoubtable [Mr.] Notovitch.”[4] Achinov’s effort was a part of Konstantin Pobedonostsev’s plan of supporting programs that used the Russian Orthodox Church (and its agents) to promote Russian culture. and the interests of the secular Russian state. In Abyssinia (as well as the Balkans, Japan, Palestine, and the Americas,) Pobedonostsev endeavored to create Orthodox communities which would be cultural and political centers for Russia.[5]

Just before the celebration of the 900th anniversary of the Christian Church in Russia, the Ethiopian emperor sent a special deputation of three Tewahedo priests to Kiev to gift the holy relic. The Abyssinian deputation, however, was delayed on the road. When the three priests of Abyssinia finally arrived in Kiev the ceremonies were over, and the Tsar was back in St. Petersburg. Before returning to Abyssinia, the venerable trio deposited the cross in Moscow in the charge of the high officials attached the Imperial. The Negus waited “with much pride and self-gratulation acknowledgment of this precious gift from his well-beloved friend and brother, the Tsar.” The weeks passed, and still no appreciative Imperial telegram arrived. The Negus, feeling much aggrieved, demanded an enquiry to be made. The Queen Sheba’s Cross never reached its destination. No Russian official could even determine what the question alluded. [6]

“I fear the unfortunate Abyssinian priests will suffer the brunt of the adventure,” said Vera Petrovna.

“The priests, of course, maintain their innocence,” said Notovitch. “But to whom is the accusation of theft to be laid? The officials to whom was assigned the task of presenting Queen Sheba’s Cross to the Tsar declare upon oath that no present of any kind had ever reached their hands. The priests possess no written evidence of having delivered it, and the officers at Moscow affirm that had a gift of such immense value been presented it would have been duly registered in the Court ledger and forwarded immediately by estafette to the Tsar.”

Nikolas Notovitch.

Notovitch had traveled extensively in India before arriving in England the previous December. He was a soldier by profession, holding a Lieutenancy in the Terek Cossacks, with whom he served during the Russo-Turkish War and was twice wounded. He was present at the battle of Plevna, and on more than one occasion acted as orderly officer to General Mikhail Skobelev. In 1882, after the war, Notovitch became a journalist for Novoe Vremya, adopting the nom-de-plume, “Dervish Nix” (the latter word being a diminutive of Nicholas, while the prefix ‘Dervish’ owed its application to his travels in the borderlands around Caucasus and Persia in “Oriental guise.”) In 1885 he went to Dagestan as a special correspondent to witness the suppression of a little uprising by Russian troops from the Caucasus. He was captured by some rebels and his career narrowly missed coming to an end, but after some weeks in captivity he was ransomed and reached Russian lines again in safety. In 1886 went to Tehran and was well-received by the Russian Legation of Persia. The Russian Minister, M. Melnikov, even took him to a reception of the Corp. Diplomatique hosted by the Shah on Nowruz (Persian New Year.) Some petty jealousies were aroused, and Notovitch made his way further east. He stayed some weeks in Egypt, surveying how the country fared under English protection. In August 1887 he arrived in India and stayed for nearly a year, but an untimely injury compelled him to leave the sub-continent. He left India for England in 1888, stopping in Persia along the way, where he was calling himself Captain Notovitch. The people of Bushehr noticed that he carried with him a small-scale map of Persia and India on which certain lines were drawn. Witnesses surmised that this map alluded to the future designs of the Russian Empire.[7] The map was incidental. Notovitch had discovered something far stranger, something along Blavatsky’s line of work, and whose opinion he was hoping to solicit.

“After the close of the Russo-Turkish War, I undertook a series of extended journeys through the Orient,” said Notovitch. “Having visited all points of interest in the Balkan Peninsula, I then crossed the Caucasian Mountains into Central Asia and Persia, and finally, last year, I made an excursion into India, the most admired country of the dreams of my childhood. The first object of this journey was to study the customs and habits of the inhabitants of India and their own surroundings, as well as the grand, mysterious archaeology and the colossal, majestic nature of the country. That I might not arouse the suspicions of the authorities in regard to the object of my visit—and raise no obstacles to a subsequent journey into Tibet—as a Russian—on my return to Leh.”[8]

Notovitch wanted to continue but Blavatsky interrupted.

“No Englishman ever believes any good of a Russian. They think we are all liars. I don’t understand how these Englishmen can be so very sure of their superiority, and at the same time in such terror of our invading India. For months they shadowed me in India, believing me to be a Russian spy!”[9]

The sound of thunder cracked outside.

Blavatsky looked at Vera Petrovna.

It was not just the weather that worried Blavatsky. In just the past week the helmet of the police-constable, Ellis, was picked up by a bargeman in Grove Park. His body was found soon after. In the East End a young man was poisoned with oxalic acid in his tea and died a violent death. Add to this the mother who attempted murder-suicide with her infant daughter that morning when plunging into the Thames. London was bending toward breaking.[10]

“I have been wandering London with my Baedecker guidebook in hand from early morning until dusk several times now, often by myself—a fact I have had no opportunity of regretting.”

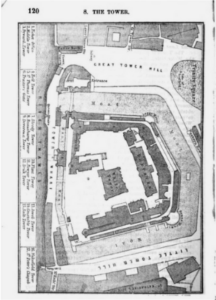

Baedecker map of the Tower of London.

Vera Petrovna assured her sister that she would be fine.

“You know there is a story about a specter, in the form of a big dog strolling about at night to make the sentries feel uncomfortable,” said Russell. “Words, too, written, or carved years ago by poor prisoners in the walls, are said to be curiously plain, even in the twilight. It is quite right that the Tower should be haunted. All the important buildings with histories are so, and why should the Tower be and exception? Ghosts always make a place so respectable don’t you think?”[11]

Vera Petrovna and Notovitch were talking of their travels as they made their way to the Tower of London.

“The truth is,” said Vera Petrovna, “I have always been a fervent student of English history and literature, and even of English life. This accounts for my great interest in the ‘Modern Babylon’ and its ways.”

View Down The Thames From London Bridge.

They reached the right bank of the Thames, near the old St Olave’s Street and Tooley Street. Just in front of them on the opposite bank of the river arose the massive (and gloomy) walls of that ancient castle-turned-prison. It was now an arsenal and a treasury ward with old relics and royal emblems.

“I hope to travel to the southern highlands of Tibet this November,” Notovitch told Vera Petrovna. “I intend on joining General Przhevalsky there. If it is possible, I will explore the road from Lhasa to Sikkim and onward through the Mussulman part of the Chinese Empire.”[12] He paused. “Would you mind going there straight and by the shortest cut?”

“I have no objection to it,” Vera Petrovna replied. “But how about the means of transit? The nearest bridge is still a good way off; and this does not seem a favorite place of resort for either bus, cab, or hansom…This is an out of the way corner, I fear. Unfortunately, I already feel sufficiently tired, as it is; and you know, one should not feel quite exhausted if one would visit the Tower. What can we do you think?”

“A very simple thing indeed,” laughed Notovitch. “We must proceed right to the Tower as the bee flies, and without stopping to look out for bridges, or waiting for cabs.”

“What can you mean with this river before us? Surely you are not St. Peter, to attempt walking on the water! I am not!”

“Very likely you are not. But follow me, and if you do, I promise to lead you straight under the walls of the Tower.”

Without waiting for an answer, Notovitch moved on. Vera Petrovna had no choice, it seemed, and did the same (though greatly perplexed as to what he was going to do.) The lane they entered was narrow, dirty, and very muddy. She had to move on with the greatest caution and care, lest she should carry away on her skirts some very undesirable souvenir of her passage. She picked up her dress as best she could, and slowly moved through labyrinth of garbage. Notovitch was hurrying away at full speed.

“It is really unkind of you to force me to lose my breath on such a hot day and leave me helplessly ignorant of where you are leading me to,” she said (mostly to herself.)

Suddenly the lane came to an end. Notovitch turned abruptly round the corner. When she did the same, Notovitch disappeared.

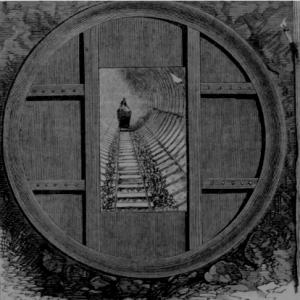

Tower Hill Station.

“Good gracious!” Vera Petrovna cried, alarmed at his unexpected exit. “Where are you?! Where have you gone to?”

“Come! come! Have no fear!” Notovitch merrily replied from some underground regions. “You are safe enough if you only follow me!”

Vera Petrovna stood on the edge of a large black hole above a winding staircase which vanished into leagues of an unknown abyss.

“Are you coming?” he cried. “Now don’t be a coward. Come bravely down. What are you waiting for?”

“Surely I have some right to hesitate when you may be leading me onto my death for all I know,” said Vera Petrovna. “What is this pit?”

A cheerful laugh was Notovitch’s only reply. Then followed the sound of quick footsteps that soon faded in the distance.

Lifting up her skirt still more carefully, Vera Petrovna grabbed hold of the damp and rusty iron railing, and, with a feeling of very natural squeamishness, made her descent down a steep, lighted, spiral-staircase. “He must know best, after all,” she told herself while counting the steps. “One, two, three—ten-twenty-fifty! Good Heavens, seventy! Ninety! Oh, Goodness!” Vera Petrovna exclaimed sandwiched between two dingy walls. “Is there ever to be an end to this?” she cried out.

“Most assuredly,” replied Notovitch, “and here we are.” He gave Vera Petrovna a mischievous glance. “Only ninety-six steps, after all. A good deal less than we should have to descend were we going down from the top of the Great Pyramid. Why should you make such a fuss over it? There! We have arrived and now we may go on again.”

“Go on, indeed! We have arrived, and we may go on, admirable and most comforting logic. But where, pray, are we going on to?” Vera Petrovna was awestruck.

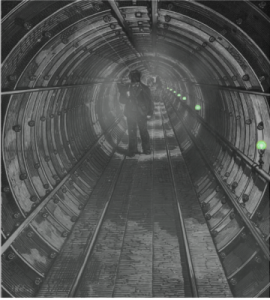

“In the belly of a meduza, yes?” said Notovitch. He was barely visible in the thick gloom of the large iron tunnel. Rows of gas-burning jets, like sepulchral lamps, whispered the memory of light. An unbroken chain of veiled phosphorescence that grew ever-fainter into an invisible end.

Notovitch was right. The subterranean corridor seemed to undulate like a machine digesting a meal. The concave walls perspired as though it were in a banya. Its sweat gathered in streams on the floor, under the feet of Vera Petrovna and Notovitch. They sloshed their way through the passage draped in a quilt of various stifling vapors. Sounds, voices perhaps, gave forth a cavernous taunt. No people were seen, only shadows; corporeal negations, and haunting disquietude.[13] Thunderous moans were heard above the slimy, vaulted, iron-ceiling. Something moved outside, thrusting itself against their narrow iron tunnel.

Tunnel at Tower Hill Station.

“What is this noise?” asked Vera Petrovna. “Where does it come from?”

“Water. It is a mighty power, you know,” said Notovitch. “It broke in once and flooded this tunnel completely.” He turned to Vera Petrovna with a placid smile. “It was soon repaired.”

“The water broke in?” Vera Petrovna cried. “Why, is it the water? I thought it was the sound of wheels.”

“What wheels would you have in the midst of a river, except those of the steamers? Boats are not noisy. Besides, they run many feet higher on the surface of the Thames. We are under it.”

Notovitch suddenly stopped.

Vera Petrovna used the opportunity to catch her breath.

“Ugh!” said Notovitch. “How it roars! Awful! We are now just in the middle of the Thames, you know. Suppose the stream finds its way in? Just the slightest fence. We should have to take to our heels. Gracious Heaven! What a run we should have for it!”

Notovitch suddenly “took to his heels” and ran through the passage.

“Now look here!” shouted Vera Petrovna protested. “Don’t!”

“I never thought you were so nervous. Do you really fear a deluge? Don’t. It is out of the question.”

“I know that!” Vera Petrovna replied. “But you have had a nice whim to lead me by such a pleasant road. Muddy, stilling, damp and dark as a pit! More tiresome, indeed, than a walk to the farthest bridge.”

It was not fear that prevented Vera Petrovna from sprinting with her companion. She was more fatigued by the heat. Like Blavatsky, Vera Petrovna possessed a philosophical disposition, and though it was of a lower temperature, it made her just as ambivalent about death. Even so, if a deluge had broken through before, who could say that it would not happen again? The sneaking thought of such a gloomy end to her story gave her a most unpleasant cold feeling down her spine.

“Truly, I am very sorry,” said Notovitch. “I thought this way would please you, as are an unusual one. You like queer things, don’t you?”

Her companion’s voice was gentle, but she sensed a slight intonation of irony. Notovitch grew very talkative and pleasant, as indeed he usually was, and offered his arm for her to lean upon as they walked to the outlet of this seemingly endless subway.

“There was once a tramway here,” Notovitch explained. “It was removed for fear of the vibration. It is a pity, isn’t it?”

“I am sure now you would like to be seated and dragged on anything…if only a wheelbarrow…isn’t it so?”

“Well, yes,” said Vera Petrovna. “I fear I shall need a good long rest. Maybe I shall not be able to see all that is to be seen in the Tower.”

“Don’t mind. We can come again when you please. Only rally your strength and courage just now. We have that flight of a hundred steps to climb at the end of the passage—you remember. ‘One can’t have two deaths, but you can’t avoid one!’”

“Do not think me more unfit for our task than I am!” laughed Vera Petrovna. “I was taken aback by this dreadful subway, I confess. But now it’s alright.”

“Very well. Glad to hear it. Ah! there’s daylight at last!” he exclaimed in a tone of relief. “One effort more! At the top of these stairs, we are in the Tower. Are you fit to go on? Shall we rest a little?”

“Oh, no! Why lose our time? I am alright…and so glad to be at last in the Tower of London.”

Vera Petrovna quickly found out that all was not quite right.

“Oh, these ever-turning steps!”

Round and round they climbed (in an endless, over-tiring rate.) When they at last reached the top, Vera Petrovna could barely stand on her legs. Her head was vertigrised with vertigo. The sun light dazzled her eyes. Her breathing grew short as though strangled with fresh air. It took all of her willpower to walk over the moat, and up to the “Traitor’s Gate,” but just in sight of the entrance to the “Record Tower” she was obliged to stop. Her legs refused to move.

“Now, there you see the most ancient walls of this place; more than eight centuries’ weight lies on them,” said Notovitch, unaware of her state of weakness. “At left is the so-called ‘Bell Tower.’ The alarm bell was rung on its top, as well as joyous volleys fired on occasions of births and weddings. Or again, perhaps, the bell tolled to signify to miserable prisoners that their death-hour had struck. At our right you perceive the mournful ‘Traitors’ Gate.’ This gate gave access from the Thames to state-prisoners, thus qualified ignominiously by their lord and master. Were they in truth traitors or not, after entering this dreary gate they had only one escape— the scaffold. I’ll show you presently, under this arch leading to the ‘Bloody Tower’ yonder—nice name, isn’t it? The very iron crooks on which they used to expose the heads of poor decapitated wretches…”

But this time Vera Petrovna saw neither the monstrous crooks, nor did she hear anymore Notovitch’s voice… But she saw and heard things far more wondrous.

“What could be the matter with me?” she thought. “Am I fainting?”

Only a moment of deafness and blindness.

She was heaved up in a glow of bright colors. A glory of light.[14]

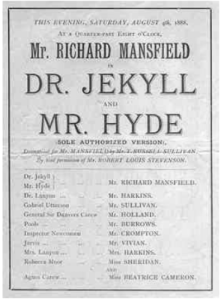

In 1887, Henry Irving, the actor-manager of London’s Lyceum Theatre, saw a performance of Richard Mansfield’s “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” while touring the United States. Impressed with Mansfield’s performance, Irving invited him to perform the show at the Lyceum in September 1888, to which Mansfield accepted. A rival actor, Daniel Bandmann, however, decided to stage his own production of Jekyll and Hyde on August 6, 1888, at the Opéra Comique. This prompted Mansfield to move the opening night of his production to August 4, 1888.[15]

Souvenir Program For Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde, Royal Lyceum Theatre, London, August 4, 1888.

“That poor woman screams so much that I can hear across the garden,” said Verochka. “How many subordinate clauses she uses! It must be horrible!”[16] She said this in gratitude and pity for the benefactor of her ticket. She then retired to her room to write a letter to her sisters and her brother Rostya before the performance.

With great effort Russell finally got Blavatsky to leave the house for her portrait. The cab had been kept waiting for hours.

“I have no out-of-door clothes,” Blavatsky protested.

Shawls and scarves were piled on.

“I will not go!” said Blavatsky. “I cannot step on wet stones.”

Carpets were spread from the door to the carriage. The wind lifted and tossed them around. Countess Wachtmeister and the coachman had to pin them down. Russell raised the umbrella over Blavatsky’s head and helped her in.

“When I first came to London it was as an Ambassadress,” Countess Wachtmeister told Russell. “In Hyde Park two powdered footmen in livery followed me. If my poor late-husband could know the day had come when I held down carpets for another woman to tread on, he would turn over in his grave.”[17]

When they arrived at Vander Weyde’s studio a crowd of people gathered.

A red carpet was unrolled for Blavatsky.

“Come along, Your Majesty!” said Russel to keep up the illusion.

Inside the studio Blavatsky looked at the portraits of the celebrities on the wall. She flatly refused to have her photograph taken. “I am not an actress,” she said. “Why have you brought me here?”

“Alright,” said Russell. “You should at least examine Mr. Vander Weyde’s experiments in the adaptation of electricity to photography.”

This grabbed her attention, just as Russell knew it would.

“I will sit for you—only one,” said Blavatsky. “Be quick—take me just as I am.”

“Now,” said Russell whispering in her ears, “let all the devil in you shine out of those eyes.”

“Why, child,” laughed Blavatsky, “there is no devil in me!”

Vander Weyde’s photo of Blavatsky.

She enjoyed the adventure but would not admit it. She told of being “bossed” and “carried as a bundle” for many months. [18]

This grand light did not blind Vera Petrovna’s eyes.

That was a velvet trance.

What awakened her to life was the (rather loud) shouts, shots, ringing bells and blaring trumpets.

Vera Petrovna looked around her wonderment. It seemed as if she had acquired new senses. She felt neither buoyed to the earth nor suspended in the air. It was as though she lived and moved simultaneously everywhere. It was like her entire being was dissolved in ether and absorbed into every atom, in all that was living and feeling on earth or in heaven. She still preserved her inner consciousness, and her external powers of moving at will. She saw, heard, and comprehended all that was taking place. All the importance and meaning of the different scenes and sights that enveloped all around her like a net. She gazed with eager surprise and perceived that she was in this same Tower of London. Yet, it was somehow different. It was a great deal larger and brighter, and full of buildings and galleries and beautiful halls. Gardens and flowers brightened the heavy towers. Handsome furniture, gold, silver, rich carpets and draperies adorned the splendid chambers of the Tower Palace. It was no longer a prison nor a fortress. It was the home of a king. Bright waters filled the moat and swept up to the thick walls under sombre arches.

A brilliant cavalcade emerged from the main entrance to receive a gorgeous procession from the river side to the Tower Palace. Guards clad in steel and brass; heralds and beautiful pages preceded their stout and stalwart king of England! The monarch slowly advanced on a great silver-white steed (well-accustomed to bear the weight of its master.) It trotted an easy pace, feeling no more the weight of King Henry VIII’s rich garments than that of its golden bridle or those white feathers which waved about its head. The king’s large thin-bearded face was bright with joy, but even his happiness could not smooth away its repulsive expression. There was pitiless in the lines of his thin lips and weighty chin. Something cold in his restless eye. His escort was numerous and magnificent, but she did not heed it. Her attention was drawn beyond the walls of this regal residence to throngs of brightly attired people, as well as to the Thames, richly decorated and studded with pleasure boats, and barges.

How this was possible, Vera Petrovna did not know, but she seemed to see it all at once. She saw the river with its smiling green banks down to Greenwich, from where came the royal bride, Anne Boleyn, in all the pomp of heraldry and power. She saw her landed amidst crowds of citizens, of civil and military trains; she heard the joyous strains of music, the roar of guns, the peal of bells and the merry shouts that welcomed her. Then she saw the Lord Mayor escorting her, with many officials arrayed in golden robes and chains, and mantles scarlet as blood. They brought her a beautiful white horse with gilded saddle and bridle set with pearls. She mounted it and went to meet the King, her amorous but passionate and heartless despot…to meet her hapless, dreary fate! Vera Petrovna looked at her…and could no longer take her eyes from her. They were riveted to that youthful form and fair face! It was a striking and beautiful face. Its charm lay not so much in the features or complexion as in its expression; mild, innocent. Truth and sweetness were written in Boleyn’s large soft eyes, in her charming smile devoid of pride and vanity. She had a strange, somewhat bewildered and enquiring look. Glancing about her, Boleyn seemed to be looking for an answer to a secret thought, to strain her mental sight as if to read, in all this brightness and glory surrounding her, her future doom. She did not see. She could read nothing. Vera Petrovna could. Vera Petrovna saw it, read it, knew what was in store for her.

The long black tresses flowed over her slender, ermine-clad shoulders, like so many serpents in her sight. The precious rubies on her crown coagulated into viscous drops of blood. The same with the gaudy, waving banners. The date embroidered on them in gold and silver, “May 29, 1533,” changed color and meaning. Vera Petrovna now read: “May 19, 1536.” Vera Petrovna saw these numbers, now large and black, everywhere. They were written above the doomed girl’s head. They were written over the walls and gates of the Tower. They were written on the broad features of her betrothed when the pair met to become man and wife. When Vera Petrovna saw them meet, everything was changed in an instant. The pile of desolate walls was now a prison. At once Vera Petrovna knew that three years had elapsed from that bright, joyful day…had passed and gone forever! All was changed! All seemed dark and mournful. Vera Petrovna saw the once happy, beloved bride again. She was pale and withered but possessed the same light of sweetness as before. She stood calm and proud in all the glory of her righteousness before her judges. She looked straight into the face of death and into the eyes of her unjust accusers, while they dared not lift their eyes to meet hers. When the fatal word “guilty” fell from the lips of her chief judge and nearest kinsman, she only shuddered, and looked upon him with silent dread. She was horrified, but not for herself. Neither fear nor despair did she feel at her own unhappy fate. She looked at her judge with wonder and mute enquiry, and then slowly lifted up her eyes and hands to Heaven, and simply said: “Oh, Father! Oh, Creator! Thou who art the way, the truth, and the life! Thou knowest that I have not deserved this death!” Her head dropped on her chest, and she was gone. Her mild protest remained as a curse on the heads of her condemners. The executioner prepared his block to sharpen his blood-stained axe. Vera Petrovna saw the martyr Queen advance to the ignominious scaffold. She heard the sinless condemned speak her last few words, her saint-like pardon to her foes. She saw her calmly lay her youthful guileless head upon the block. When the axe was lifted above her neck, Vera Petrovna rushed to avert the blow with all the strength of her will. She saw no more.

A moment of profound unconsciousness.

Half astounded as by a fall from the clouds.

Vera Petrovna found herself lying on the cold steps of the Wakefield Tower. She was in front of the closed and silent “Traitors’ Gate” of the Bloody Tower. Notovitch was distressing over her, holding her head, rubbing her hands. Then she saw someone forcing a glass of cold water on her. She took it and drank it with the utmost pleasure. When Vera Petrovna caught sight of who gave her the water, she was again bewildered. The man looked as if he represented the residue of her recent vision.

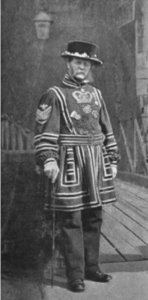

A Yeomen of the Guard.

He wore a red and golden attire, a queer round hat, which reminded her of the top hat of a droshky coachman. He was one of the twenty in the corp. of Yeoman Warders who lived in the Tower. Had it been daytime the Yeoman would have worn the new blue uniform, but it was no longer day.[19]

“Well, who is this?” said Vera Petrovna. “What are you moaning and grumbling over me for?”

“This is quite like you,” Notovitch cried. “Just returned to life and asking questions about indifferent things. He is the yeoman…the keeper…One of the official guardians of the Tower. And how do you feel now?”

“How do I feel? I am very well, thank you.”

“Very well! You’re just recovering from a dead swoon! What was the matter with you, for goodness’ sake? Why did you not tell me at once that you felt ill?”

“I felt ill? But, not at all! I felt perfectly well indeed, and enjoyed myself, I can assure you, for I saw a wonderful sight. I have seen the arrival of Anne Boleyn at this very place! Henry VIII. meeting her at the main entrance. Oh, it was an exceedingly beautiful and striking procession, I tell you. After that, I saw her judged and sentenced. Oh, the lawless, monstrous deed! I saw the poor, young, harmless thing led to the scaffold. I rushed to her rescue—and then…all disappeared…I felt as if I could tear the headsman to pieces.”

“Oh, indeed? Hush! Don’t!” were the distressed and pleading entreaties of my poor friend. He was frightened to death lest he should have to take me to a lunatic asylum, instead of my home.

“No, don’t! Do for goodness’ sake be calm,” he went on. “Why you must be very ill indeed. You are delirious, my dear madam.”

“Delirious yourself!” Vera Petrovna cried. “I never was more in earnest. I have seen all this and much more I tell you.”

“Yes, yes! Certainly, you did,” he said soothingly. “But now, you see, we must go home. You are overtired! Indeed, you are! I have sent for a cab.”

“What for? Am I to go home without looking inside these towers? Now, when I am most interested and eager to see them. Go home?!” she indignantly protested. “Take the cab for yourself! I will not.”

“This is impossible. You may feel worse. We will come here tomorrow, but you must have some rest first,” he implored.

“I have had rest enough,” replied I, so very decisively that he was taken aback. “Now, give me your arm and show me the Tower, or I will go along by myself. I am neither mad, nor sick, nor tired, and I will have my own way.”[20]

The Lyceum. 21

“Scoundrel, leave my house.”

“Eh,” laughed Hyde, defiantly, “—that’s good.”

“Monster! Who and what are you? Go, or—”

“Go? Why, why I will make this house mine, the girl mine if I please.”

“Infernal villain,” yelled Sir Danvers, lunging at Hyde, “I’ll—”

Hyde easily tossed his attacker aside. “Hands off, or it will be your death, I warn you.”

Sir Danvers grappled with Hyde at centerstage. “By heaven! I’ll—”

“Eh? Good!” said Hyde. “One more, one less, what does it matter? There! If you will have it.”

The men struggled about the stage, but Hyde eventually throttled the neck of Sir Danvers.

“Help!” cried Sir Danvers, as his life was squeezed from him. “Help!”

Agnes rushed in from the door on stage right.

The curtain quickly dropped.

The actor triumphed, for he held the audience. His nervous electricity caused silence throughout the house—the surest test of power. Badly executed, such a scene would have created roars of laughter or have been hooted off the stage. But the curtains fell upon a shock if silence, followed by a roar of sympathetic applause, not for the scene, for it was indefensible, but for the actor who was unquestionably clever.

“Poor Jekyll killed his bride’s father!” gasped Vera, wordlessly.[22]

Finally, feeling completely at the mercy of the spirit, Jekyll decides to poison himself and begs his friend to bring his bride to look at her before dying, but he asks to hurry up, because he feels that he will soon find him.

Jekyll bolted the doors behind him. “And so farewell, for we shall never meet again—I know it. I am left to face my death alone. Ah, were death all.”

Jekyll crossed stage right.

“It is the other nameless terror that racks me, terror of myself—for we are one.” Jekyll shivered at the thought. “Again, that shudder of the grave! Have we changed places already?” Jekyll said, looking in the mirror. “No, not yet—” Jekyll sank into a chair and burst into tears. “Poor fool! To waste time like a woman in tears.”

Crossing to a desk left of center, Jekyll retrieved some papers from a desk and began to write.

“This is my full confession—I have not spared myself: ‘For Gabriel Utterson. Let him deal with it as he pleases,’” laughed Jekyll bitterly. “And here my will revoking the other which he holds. He will like this better—it cancels the bequest to Hyde—what could Hyde do with money. Poor hunted wretch, the wealth of London would not save him now.” Jekyll wrote another note. “This too is for Utterson,” he said, rising with a shiver. “It has come, the devil’s hand is at my throat. No, it is past.”

Jekyll stood near the window at the back of the stage, bathed in the light of the moon. “He only has so much time,” Vera thought, “through these disgusting and terrible antics, of crawling and jumping, to drink that poison!”

“Agnes,” said Jekyll at the center of the stage. “Where is Agnes, he promised that I should see her.” He shuffled to the window and opened it. “She must come quickly, or I shall be gone. Night is closing in! The stars are coming out. How often together Agnes and I have wondered at them! And now, for me, no dawn, no twilight—only the outer blackness of the grave. Will they never come?” A sound is heard offstage. “Footsteps!” Jekyll looked out the window and drew back once more. “An inspector of police. Well—and why not? Dr. Jekyll surely may take a breath of air unchallenged. I am like a child and start at nothing. He is gone again. No sound but the roar of London. Hark! I heard voices. Lanyon has kept his promise. She is there. They pass. She must know nothing. I will not have it so. I must speak, if only one word. Agnes! Agnes! Look it is I Henry Jekyll. She has seen me, she will come! Thank you, heaven!” Jekyll fell into a chair center right. “She will come! I shall hear her voice! Shall see her once—only once—before!”

Vander Weyde’s publicity photo of Mansfield in the dual role of Jekyll and Hyde.

Jekyll slowly morphed into Hyde, and seeing himself in a mirror, rose with a shriek, “AH!”

“It is terrible to see this good, noble person, sense the approach of that freak,” thought Vera. “How…he transforms from a handsome person, with a clever open face, into a hunched…haggard…evil…devil.”

“Jekyll!” cried Utterson, off stage right, “Jekyll!”

“Utterson!” said Hyde, in an aside to the audience, “—the Police!”

The police knocked repeatedly on the door.

“Jekyll!” yelled Utterson, “I demand to see you. If not of your consent, then by brute force!”

“Utterson!” cried Hyde, “For God’s sake—have mercy!”

“This actor plays the part remarkably well,” Vera thought. “The transformation is instant—he is simply unrecognizable!”

“That’s not his voice!” shouted Utterson, “Down with the doors!” [Heavy blows to the doors.] “The poison—here—” said Hyde, in an aside to the audience. He walked over to a table stage right and picked up a phial. Just as he lifts the poison, the doors are broken down, and Utterson, Poole, Lanyon, and Agnes enter the stage. Utterson crossed to the front of the table. The others remained in the doorway.

A fearful cry of despair echoed throughout the Lyceum as Jekyll disappeared forever. The malignant Hyde leaped down the stage, swallowed the poison on the table, and fell in his death throes just as the door is broken in and the detectives entered the room.

“Murderer!” cried Utterson. “What have you done with Jekyll?”

“Gone,” shouted Hyde. “Gone!”

Hyde dies.

Lanyon advanced to the body. Poole crossed to the back of the table. Agnes ran to Lanyon.

“Who is there?” Agnes asked.

Lanyon tried to prevent Agnes from viewing the body.

“It is my master!” Poole declared.

[Curtain.]

Verochka returned to 17 Lansdowne to find Blavatsky sitting at a table with a green baize cover which bore her chalk graffiti of occult symbols and her score for card games.[23] As was her evening custom, she was playing a game of “Solitaire,” or “Patience,” as it was known. Her followers had deduced that there was something more behind the reason why she played the game, but they were not sure. As the layout suggested, it was a form of cartomancy, that is, it was a way to use cards for divination.[24] There was no need to explain why she played, nor was there incentive. As one British newspaper stated in the day before: “English law severely punishes the practice known as fortune-telling, it is one which is secretly followed by a great number of women in various parts of the country.” The paper added: “As long as human nature remains as it is it will contain a large taste for the occult and the mysterious.”[25]

“Did you enjoy the performance?” Blavatsky asked.

“He died very well, without unnecessary things,” said Verochka, “only, falling face down on the floor, and running his nails several times on the carpet.”

Verochka. 26

“It is curious to note that Mr. Stevenson, one of the most powerful of our imaginative writers, stated that he is in the habit of constructing the plots of his tales in dreams,” said Blavatsky.[27] “Our best modern novelists, who are neither Theosophists nor Spiritualists, are beginning to have very psychological and suggestively Occult dreams. No grander psychological essay on Occult lines exists than Mt. Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”[28]

“Is such a thing possible Aunt Lelya? To become such a creature?”

“In Occultism we call it the ‘Dweller on the Threshold,’” said Blavatsky. “This ‘Dweller’ is not like that which is described so graphically of Bulwer-Lytton’s Zanoni, but an actual fact in nature and not a fiction in romance.”

“Is that the work which Baba Hahn translated?”

Elena Hahn. (Blavatsky’s mother/Verochka’s grandmother.)

“No, that was Godolphin,” said Blavatsky. “Bulwer-Lytton must have got the idea for his ‘Dweller’ in Zanoni from some Eastern Initiate. Our ‘Dweller,’ led by affinity and attraction, forces itself into the astral current, and through the Auric Envelope of the new tabernacle inhabited by the Parent Ego, and declares war to the lower light which has replaced it. This, of course, can only happen in the case of the moral weakness of the personality so obsessed. No one strong in his virtue, and righteous in his walk of life, can risk or dread any such thing; but only those depraved in heart. Stevenson had a glimpse of a true vision indeed when he wrote his Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. His story is a true allegory. Every student of the Occult would recognize in it a substratum of truth. Mr. Hyde is a “Dweller,” that is, an obsessor of the personality, the tabernacle of the “Parent Spirit.” ’This is a nightmare tale!’ I was often told by a person who had a most pronounced ‘Dweller,’ a ‘Mr. Hyde,’ as an almost constant companion.”

“How can such a process take place without one’s knowledge?” asked Verochka.

“It can and does so happen,” said Blavatsky. “The Soul, the Lower Mind, becomes as a half animal principle almost paralyzed with daily vice, and grows gradually unconscious of its subjective half, the Lord. In proportion to the rapid sensuous development of the brain and nerves, sooner or later, the personal Soul finally loses sight of its divine mission on earth. Truly, like the vampire, the brain feeds and lives and grows in strength at the expense of its spiritual parent and the personal half-unconscious Soul becomes senseless, beyond hope of redemption. It is powerless to discern the voice of its ‘God.’ It aims at the development and fuller comprehension of natural, earthly life; and thus, can discover but the mysteries of physical nature. It begins by becoming virtually dead, during the life of the body; and ends by dying completely––that is, by being annihilated as a complete immortal Soul. Such a catastrophe may often happen long years before one’s physical death. We elbow soulless men and women at every step of life. When death arrives, there is no more a Soul to liberate, for it has fled years before. Bereft of its guiding principles but strengthened by the material elements from being a ‘derived light,’ now becomes an independent Entity. After suffering itself to sink lower and lower on the animal plane, when the hour strikes for its earthly body to die, one of two things happens: either it is immediately reborn in the state of Avichi (Hell) on earth, or, if it grows too strong in evil––‘immortal in Satan’ to use an Occult expression––it is sometimes allowed, for Karmic purposes, to remain in an active state of Avichi in the terrestrial Aura. Then through despair and loss of all hope it becomes like the mythical ‘devil’ in its endless wickedness. It continues in its elements, imbued through and through with the essence of matter; for evil is coeval with matter rent asunder from spirit. And when its higher Ego has once more reincarnated, evolving a new reflection, the doomed Lower Ego, like a Frankenstein’s monster, will ever feel attracted to its ‘Father,’ who repudiates his Son, and will become a regular ‘Dweller’ on the ‘threshold’ of terrestrial life.”[29]

Vittoria Cremers, unbeknownst the Blavatsky and Verochka, listened at the door with great interest. “Dweller at the Threshold?”

THE AGONISED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS:

INTRO: CHARLEY.

I. WITCH TALES.

II. CARELESS WHENCE COMES YOUR GOLD.

III. THE TIMES ARE CHANGED.

IV. DENIZEN OF ETERNITY.

V. DOMOVOY.

VI. WITH LOW AND NEVER LIFTED HEAD.

VII. IMPERIAL GOTHIC.

VIII. THE SERVANT OF THE QUEEN.

IX. THE DWELLER ON THE THRESHOLD.

[APPENDICES]

A SWASTIKA WITHIN A CIRCLE.

THE ENGLISH IN INDIA I.

THE ENGLISH IN INDIA II.

THE ENGLISH IN INDIA III.

SOURCES:

[1] “The Weather Today.” The London Evening News. (London, England.) August 4, 1888; “London Weather Forecast This Day.” The London Evening Standard. (London, England.) August 4, 1888; “A Great Storm.” The North London News. (London, England.) August 4, 1888.

[2] Russell, Edmund. “As I Knew Her.” The Herald of the Star. Vol. V, No. 5. (May 11, 1916): 197-205.

[3] Though Vera does not mention Collins by name, she states that she could “hear across the garden,” where Collins lived: “My dear girls, I saw enough fears yesterday. One poor, remarkably beautiful Theosophist who is currently undergoing an operation, which is why she screams so much that I can hear across the garden (it’s horror, how many subordinate clauses), sent me a ticket to the theater.” Johnston, Vera Vladimirovna. “From the Letters of Vera Vladimirovna Johnston.” August 5/ July 29, 1888, London, England

[4] “An Abyssinian ‘Moscow.’” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) February 27, 1889.

[5] Byrnes, Robert Francis. Pobedonostsev, His Life and Thought. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana. (1968): 221.

[6] “London Gossip.” The Birmingham Daily Post. (Birmingham, England) August 24, 1888.

[7] “Current News.” The Bangalore Spectator. (Bangalore, Karnataka, British India) August 10, 1887; “Persia.” Homeward Mail from India, China and the East. (London, England) April 3, 1888; “At Home and Abroad.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) October 9, 1888; “M. Notovitch in India.” Civil & Military Gazette. (Lahore, British India) November 26, 1888; “The Design of Russia Revealed.” Civil & Military Gazette. (Lahore, British India) December 1, 1888.

[8] Notovitch, Nicolas; J.H. Connelly (tr.) The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ. R.F. Fenno Company. New York, New York. (1890): Preface.

[9] Johnston, Charles. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Part I.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. V., No. 12. (April 1900): 221-225.

[10] “Shoreditch Poisoning Mystery.” Echo. (London, England.) August 1, 1888; “Supposed Murder at Richmond.” The London Evening Standard. (London, England.) August 1, 1888; “Charge of Attempted Murder and Suicide.” The Illustrated Police News. (London, England.) August 1, 1888.

[11] “A Story of the ‘Tower.’” Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday. (London, England): September 15, 1888.

[12] “Bombay News.” Civil & Military Gazette. (Lahore, British India) December 1, 1887.

[13] De Amicis, Edmondo. Jottings About London. Alfred Mudge & Sons. Boston, Massachusetts. (1883): 40.

[14] [Zhelihovsky] Jelihovsky, Vera P. “An Adventure in the Tower of London.” Lucifer. Vol. III, No. 13 (September 15, 1888): 21-29.

[15] Danahay, Martin A., and Alexander Chisholm, eds. Jekyll and Hyde Dramatized: The 1887 Richard Mansfield Script and The Evolution of The Story on Stage. McFarland & Company. Jefferson, North Carolina (2005):15-16, 55-57, 77-78; “Lyceum Theatre.” The Daily Telegraph. (London, England) August 6, 1888; “The Nightmare at The Lyceum” Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) August 7, 1888; “Last Night’s Theatricals” Loyd’s Weekly Newspaper. (London, England) August 5, 1888; “Lyceum Theatre” The Daily Telegraph. (London, England) August 6, 1888.

[16] Though Vera does not mention Collins by name, she states that she could “hear across the garden,” where Collins lived: “My dear girls, I saw enough fears yesterday. One poor, remarkably beautiful Theosophist who is currently undergoing an operation, which is why she screams so much that I can hear across the garden (it’s horror, how many subordinate clauses), sent me a ticket to the theater.” Johnston, Vera Vladimirovna. “From the Letters of Vera Vladimirovna Johnston.” August 5/ July 29, 1888, London, England

[17] Russell, Edmund. “As I Knew Her.” The Herald of the Star. Vol. V, No. 5. (May 11, 1916): 197-205.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Yeoman Warders of the Tower of London.” The Graphic. (London, England) January 28, 1888.

[20] [Zhelihovsky] Jelihovsky, Vera P. “An Adventure in the Tower of London.” Lucifer. Vol. III, No. 13 (September 15, 1888): 21-29.

[21] Brereton, Austin. The Lyceum and Henry Irving. Lawrence & Bullen, Limited. London, England. (1903): 325.

[22] All of Vera’s “internal dialogue” are taken from a letter that she wrote to her sisters the day after the performance. Johnston, Vera Vladimirovna. “From the Letters of Vera Vladimirovna Johnston.” August 5/ July 29, 1888, London, England

[23] Yeats, William Butler. Four Years. The Cuala Press. Dunlin, Ireland. (1921): 71-80.

[24] Fussell, Jr., Paul. “E.M. Forster’s Mrs. Moore: Some Suggestions.” The Philological Quarterly. Vol. XXXII, No. 4. (October 1953): 388-395.

[25] A.F. R. “London Correspondence.” The Boston Spa News. (Yorkshire, England) August 3, 1888.

[26] “Serge Julich Vitte.” The Review of Reviews. Vol. VIII, No. 5. (November 1893): 490-494.

[27] Blavatsky, Helena P. “The Signs of the Times.” Lucifer. Vol. I, No. 2. (October 15, 1887): 83-89.

[28] Blavatsky, Helena P. The Secret Doctrine Vol. II: Anthropogenesis. The Theosophical Publishing Company. London, England. (1888): 317.

[29] Blavatsky, Helena P. Collected Writings Volume XII (1889-1890.) Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1980): 636-638. [E.S. Instruction No. III.]