May 11, 2023

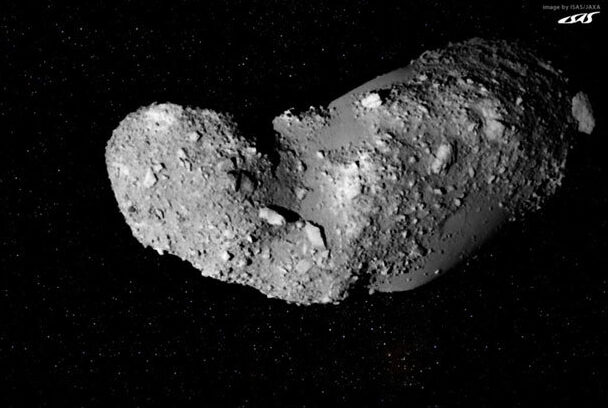

Itokawa, a rubble pile asteroid, photographed by Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa.

Image credit: NASA/JPL

New research flips our knowledge of ‘rubble pile’ asteroids on its head.

Once in a while, a scientific result emerges that flies in the face of what we intuitively expect. It’s one of the things that makes science appealing – you never quite know what will turn up.

Some recent work led by scientists at Curtin University now falls into that category. And the quirky title of their research paper – “Rubble Pile Asteroids are Forever” – gives a strong hint of what it’s about.

When we think of asteroids, most of us imagine mountain-sized lumps of rock floating in space, and that’s a reasonably accurate description. But sometimes those lumps of rock aren’t as solid as they look, and turn out to be an aggregate of stones and dirt loosely bound together by their own gravity.

This is revealed by the asteroid’s low density, suggesting that much of its interior is empty space. These ‘rubble pile’ asteroids have usually been considered to be relatively fragile, suggesting that a collision with another asteroid would pulverise them completely. But the new research turns this idea on its head.

The evidence comes from three microscopic specks of dust returned to Earth by a Japanese spacecraft in 2010. The dust grains came from a 535m-long rubble pile asteroid called Itokawa, and were part of a trove of 1500 or so particles collected by the spacecraft. By analysing deformed crystal structures in the grains, along with isotope dating, the Curtin team was able to estimate how long ago the impact that created the asteroid took place.

What amazed the scientists was that the time estimate, of more than 4.2 billion years, is about 10 times longer than the average lifetime of solid rock asteroids before they, too, are demolished in collisions.

Further analysis shows the rubble pile structure appears to absorb the effect of impacts, acting like a giant ‘space cushion’. The fact that rubble pile asteroids could be very difficult to destroy suggests they might be more numerous than previously thought.

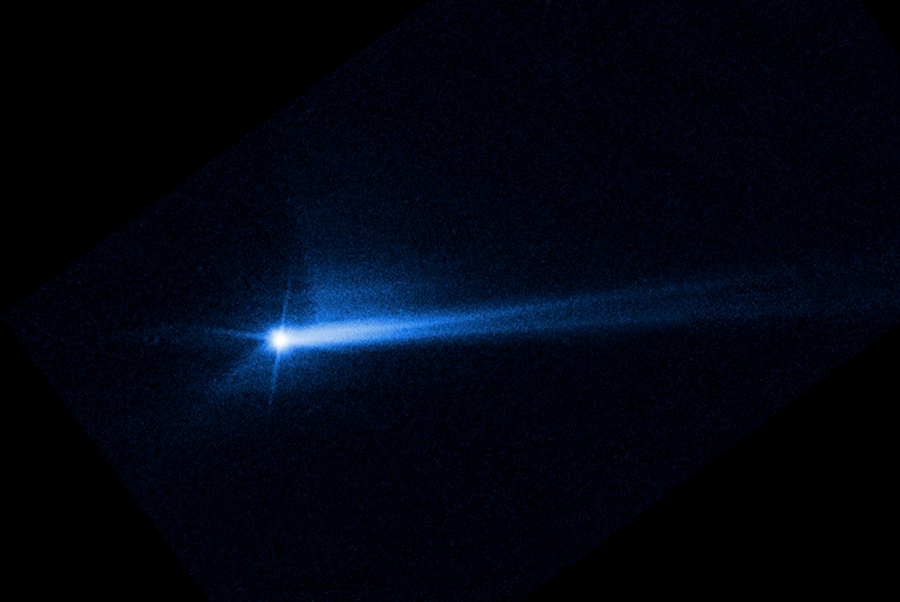

In turn, this discovery hints that any future asteroids threatening the wellbeing of our planet could be rubble piles rather than solid rock, and their robustness against external shock could be advantageous if a mission was mounted to deflect one. The shockwave from a nearby nuclear explosion, for example, might be enough to redirect the asteroid rather than split it into the many dangerous fragments that would be expected from a solid rock asteroid.

Related: NASA’s asteroid deflection mission was more successful than expected

Related: NASA’s asteroid deflection mission was more successful than expected