PUNK

Irvine punching logs in Pensacola, Florida.[1]

Irvine’s last job in the South was working as a longshoreman in Pensacola, Florida punching logs in the harbor for a dollar and six “bits” a day. On the beach, amid the wreckage of Hurricane that devastated the coast in the summer of 1906, Irvine met two of the peons in the recent trial involving the Jackson Lumber Company.

Aftermath of the “Great Hurricane” 1906. (c/o) UWF Historic Trust.

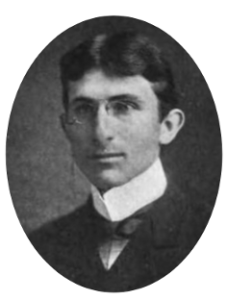

They sat together on a pile of driftwood on the shore of the Gulf of Mexico and introduced themselves. They were Herman “Square Head” Orminsky and Arthur “Punk” Conti (who preferred the surname “Buckley” because it sounded more “American.”) Orminsky was a bright young Russian Jew who had traveled a long distance for freedom. Having successfully evaded the horrors of the ultra-nationalist “Black Hundred” during Kishinev Pogrom of 1903, he was contemplative and studious boy, and well-versed in Tolstoy. He hoped to return to Russia one day. “There when we suffer, we suffer all together for liberty and freedom,” said Orminsky in broken English. “Here we suffer bad punishment for just our belly stomach.” Irvine was at once reminded of the talks he had with Maxim Gorky the previous year.[2]

Herman “Square Head” Orminsky.[3]

While they were talking, a dog approached the group looking for a friend. It walked past Irvine but nuzzled up to Punk, licking his hand as familiarly as if they had been pals for years.

“I worked for the Humane Society back in New York,” said Punk. “I spent my days on the streets in the interest of stray and neglected dogs!”

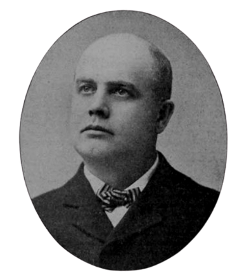

Arthur “Punk” Conti.[4]

Punk was short for someone his age, with the face of a boy and a soft mild voice. His eyes were large and black, and his tangled black hair fell loosely over his brow. The son of Italian immigrants, the seventeen-year-old “Punk” grew up in New York’s “Little Italy” in a big dark tenement at 2207 First Avenue.[5] The Contis occupied two rooms on the third floor that were illuminated by lamp both day and night. (The light of the sun ever entered their home.) The fire escape which ran the length of the rooms was a receptacle for what their rooms couldn’t hold.

“Typical ‘New Law’ Tenement” Upper East Side, Manhattan.”[6]

“My father was a hod-carrier,” said Puck. “My mother died before I was five. I remember being awakened one morning by her warm kisses on his lips. I saw the love in her eyes in the yellow rays of lamplight. We laid together in the bed. Then they took her away—away from sight forever. I couldn’t cry, but I had a very sore heart. Another mother came and took my brother, and sister, and me. Then others came. The two rooms were crowded. My second mother had much care and some sorrow. She was one of those who imagined that sorrow can be drowned in liquor. I was sent to a ‘soup school.’”

New York Catholic Protectory.[7]

“What’s a soup school?”

“A Mission School in the neighborhood,” said Punk. “I went there for year. When my father died in Harlem Hospital in 1902, I was put away in the New York Catholic Protectory at Westchester.”

~

In the 19th century, America’s cities faced mass immigration from poor Europeans. The Great Famine of Ireland brought many Irish to New York City (where they faced antagonism, alienation, and poverty.) The Nativists who discriminated against them were openly anti-Catholic. These immigrants lived in squalid conditions (disease, overcrowding, etc.) 15,000 vagrant and destitute children lived just in the Five Points neighborhood (of Manhattan) alone. The American Civil War further left many fatherless children and widows. This accelerated the instability of families suffering in poverty. Children as young as five were arrested for vagrancy and truancy. A great many of these homeless children were placed in the poorhouse on Randall’s Island.

Charles Loring Brace, a native-born social reformer founded the Children’s Aid Society to feed, clothe, and house children who were left fending for themselves on the streets. Brace, however, regarded the Irish (the largest group of immigrants) to be “dangerous classes” and of “inferior stock.” Catholics, naturally objected to the Society’s proselytizing shelters, Protestant Sunday schools, their orphan train program. Started in 1853, the “orphan train” sent these Catholic children into the American West where they were placed in the homes of Protestant farm families. Many of these children were not fully orphans or even half-orphans. Civil Administrators of Poor Laws, however, routinely invoked a limited “assumption of paternity” clause to end parental rights. Though this would come as no surprise to anyone (except Civil Administrator,) this termination of parental rights severely undermined the family unit, and directly threatened its economic survival. Additionally, the Children’s Aid Society changed these children’s names, making it nearly impossible for their families to trace them.

“Orphan Train.” (c/o Children’s Aid)

In response, the New York Catholic Protectory was established in 1863 as a care-home for destitute children. In 1865 the Protectory, having outgrown their original Manhattan quarters, moved to a large farm in The Bronx (then known as the village of West Chester.) Over time, it became the largest child welfare organization in the country, and the Protectory’s methodology would influence the emerging field of social work.[8]

~

“I stood there at the Protectory for about three years,” said Punk. “I was taught a little military drill, some caning of chairs, and much prayer. I left in June 1905, when I was sixteen.”

“Where’d you go?”

“Well first I went to an out station of the Protectory. That was at 415 Broome Street. That’s where I met Brother Barnabas—he’s the captain of the ‘Placing Out Bureau.’”[9]

~

Brother Barnabas McDonald. (Source: Wikipedia.)

Brother Barnabas McDonald was a notable leader in the field of welfare institutions. Born in 1865, Brother Barnabas entered the novitiate when he was twenty. After some years teaching in elementary schools, he was assigned to the “Placing Out” Bureau. Brother Barnabas soon recognized that the institution was inadequate in its endeavor to “re-home” young urban boys in rural areas, as there were few Catholic families outside the cities. The boys were more often than not exploited. They were given farm work for which they were not trained, in a setting that was hostile to their religion. In 1894 the Archbishop of New York commissioned Brother Barnabas to undertake a wide survey of similar institutions. His investigation took three years to complete, as he traveled to 10 states and parts of Canada. When he returned to the Placing Out Bureau, he opened a halfway house of sorts called the St. Philip’s Home where the boys who were discharged from the Protectory could live in a semi-domestic atmosphere and ply the trades which they had learned. The boys were expected to pay for their board and assume responsibility for maintaining order in the house. What Punk called the “soup school” was the “cottage system,” an alternative to the institutional model of caring for orphaned youths.[10]

489-493 Broome Street. (Source: DYMNY)

“I got permission one day to work my way on a river boat to Albany,” said Punk. “I didn’t care where the thing was going. It was enough that I was on board with a chance to work. I worked a few months for a farmer who lived some miles from Schenectady. The work got heavier on the farm, so I wore off and he returned to Albany. After that I got that job on the wagon of the Humane Society.”

“So, how’d you end up down here?”

“Well, I returned to Manhattan and stood up in the newsboys lodging for three days. That’s where I met “Stony” and Murphy. We were on our way to a labor agency called ‘The Farmer’s Rest,’ but as we passed by Reese’s Reliable Employment Agency (53 Greenwich Street,) we were accosted by an agent who wanted a hundred men and wanted them at once. Mrs. Reese made us feel at home. Mrs. Reese tricked us with fairy stories of the fortunes laborers made in the South. She had some stock story about a fella who made a thousand dollars in less than two years! Well, from the employmency we joined thirty-six other men and sailed on the S.S. Kansas City to Georgia. I told them my name was ‘Buckley.’”

S.S. Kansas City.

“Why’d you tell them that?” asked Irvine.

“I think it sounds ‘American,’ you know?”

“I suppose.”

“There was an Irishman with us named Joe McGinnis,” said Punk. “Joe made things more than lively on the voyage. He paid special attention to the Hebrews, especially Orminsky. Joe got him asleep, and with a pair of scissors, clipped the shape of a cross on the crown of his big bushy head of hair! ‘There now!’ said Joe. ‘Begorra, if the ship sinks there’s hope fur ye, ye blinderin’ blackguard!’ There was trouble on the ship on account of that, but the captain appeared with a revolver and peace was restored. We all called Orminsky ‘Square Head’ after that. Oh, Joe got me too! He’s the one who first called me ‘Punk,’ and the name stuck.”

~

The “slang question” occupied the minds of the American public in the first decade of the twentieth-century.[11] The influx of immigrants meant an influx of new languages. It was widely-reported that slang was “hailing sign and password of the craft” of thievery. (The word “slang” itself originally referred to the “special vocabulary of tramps or thieves.”) Philologists of the Progressive Era traced the origin of “thieves’ slang” to the “Gypsies” of Europe. (It was assumed that the Romani people were from originally from Egypt, hence the appellation “Gypsy.”) These linguists determined that their language bore more resemblance to Sanskrit and Hindi. Popular “Gypsy” words adopted into English like “bloke” and “pal” were etymological cousins to “loke” (Hindi: “a man.”) and phral (Romani: “brother/comrade” from Sanskrit bhrata.)[12] Mirroring this organic change in language was the Simplified Spelling Movement which made significant strides in 1906. Streamlining and simplifying English words, it was argued, would shorten the years required in schools, and aid in the education of recently arrived immigrants.[13] As for the word “Punk,” it was slang for “young male criminal.”[14]

~

“A Consignment of Laborers on Shipboard, Bound for a Southern Labor Camp.”[15]

“We were met at Savannah by Mr. Le Maistre,” Punk continued. “I had a contract in my pocket to work for the Jackson Lumber Company. I thought was an honorable understanding. Mr. Le Maistre treated us all very kindly at every point on the journey.”

~

In the spring of 1906, the Jackson Lumber Company needed laborers. The regular agencies were unable to supply the demand. The company experimented with the novel concept of creating their own labor agent. For this position they hired an educated Hungarian man named Eugene P. Newlander. For $1,200 (with expenses paid) Newlander would send 100 men a month to work in Lockhart. Experiments with cheap labor were expensive and time consuming. A man who sold shoelaces in the Bowery was not transformed into a lumber jack overnight. If men chose to leave their job, it was a great loss to the company no longer. Those who escaped were quickly hunted down with bloodhounds and returned to the camp.

The catalyst for the recent investigations into the labor practices at Jackson Lumber Company were the testimonies of Punk’s fellow laborers from New York, namely the Hungarian immigrants named Rudolf Lanniger and a Mikhail Trurich. In June 1906 Lanniger arrived in New York. In July 1906 he was sent to the Jackson Lumber Company by the labor agents, Frank & Miller (201 E. 2nd Street.)[16] When Lanniger and Trurich group arrived in Savannah they were handed over to Dr. W. G. Grace (the veterinarian of the company) and traveled by rail to Lockhart.

Dr. W.G. Grace.

Gallagher, the “bull of the woods,” gave the newcomers an idea of law that only Orminsky, knowing the terror of Cossack tyranny, could properly understand. Joe McGinnis came to a deadlock with an odoriferous bunk-mate. Gallagher pulled McGinnis from the box car. “You ain’t running this camp,” Gallagher growled. He then drew a pistol and fired three shots so close to McGinnis’ face as to burn his flesh with the powder. McGinnis dropped to his knees and begged for his life. Punk stood by trembling.[17]

The following day then men were assigned their jobs. Lanniger was assigned to the turpentine camp and tasked with chipping wood for $1 a day. It was not the job he agreed to perform with the labor agents. Everything, in fact, (work, wages, hours, and conditions) was all different from the contract he signed. Nevertheless, Lanniger agreed to the work.

Oscar Sandor.[18]

Trurich was not as complacent as Lanniger. The day after their arrival, Trurich left the camp. He was soon overtaken by Grace, Gallagher, and Sandor riding in a buggy with their bloodhounds. Grace subdued him with one hand while covering him with a revolver in the other. Gallagher horsewhipped him. Sandor, the Hungarian interpreter of the camp, remained in the buggy and contented himself with mocking his fellow countryman in their native tongue. “If you try to escape again, they will shoot you down!” said Sandor. “If we find you alone in the woods again, we will kill you. Only God will see.”[19]

~

Hughie the cook needed a helper. Punk got the job. It was looked upon as a sinecure. It lasted a week. Punk was sent to carry water to the sawyers. It was Bellinger, Gallagher’s assistant, who gave the orders. Punk’s mind worked on a definite order, as a cash register might. In his mind the truest course of action was to do exactly what he was instructed, neither more, nor less. He was to provide a certain section of men—a number of gangs—with drinking water. Men of other drifts demanded water too. Punk refused. He made his appeal to authority. The men told Gallagher.

“Give him hell!” Gallagher said. “Hold him till Bellinger gets at him!”

Bellinger was the best-natured man in the camp and had a kindly face. He always carried a revolver and sometimes a couple of them, but he didn’t have a brutal nature. In a close study of Bellinger, Irvine could find but one explanation of his brutality—it was part of his business. Bellinger told Punk that he had a new job for him. “It was in the barn.” Bellinger called Ollie, the biggest man in camp, and Jones, the blacksmith. They entered at the same time. Punk was told to arrange his own pillory. He was still unsuspecting. When ready, Ollie and Jones seized him and bent him over the block. Punk screamed.

Bellinger struck the first blow with a stout thong. The weapon curled like a snake around Punk’s ribs. Blood spurted into his ragged shirt. Bellinger, panting for breath, and with sweat pouring over his face, continued to flog the screaming boy, stopping only for moment to rest. The thong raised a welt on Punk’s back every time it fell. Sometimes it cut clean. He imagined for a moment that it was over, but with a fresh supply of breath Bellinger began again, and continued until, with sheer exhaustion and inability to go on, he stopped. “Let the Dago go.”

Bellinger gave Punk fifty lashes—a number that even in the most brutal of stockades seldom gave to even the most abandoned criminal. Punk was then handed over to Fagar, an under-boss. Fagar did not work him long. Mike, the engineer of the “four- spot” (an engine marked 4,) asked to have Punk appointed his fireman. For two weeks Punk could not sit down at meals—he stood at the end of the table to eat his portion. At night in his bunk, he lay on his stomach. The sores festered and bled profusely. It was the sight of the boy standing at his meals, pale and trembling with pain, that moved the heart of Mike, the engineer. He had too much bending to do, however, and three days were all he could stand of it. The pain was excruciating. Mike often found Punk weeping in silent appreciation and in fear of worse treatment.

Then Orminsky got flogged. This brought them closer together.

“I ached in pain in the burning sun, so I leaned against a tree and rested,” said Orminsky. “Then I was told that there was another job for me in the barn. When I arrived, they flogged me. They flogged me every day. I know not for what I be hurt. I work hard till blood is on my hands; then I get hurted with whip all the same!”

Then came the German visitors, Emil Lesser of Birmingham, a sort of semi-official investigator from the German Immigration Association, and German Vice Consul Rolf.[20] All eyes were on Punk and Orminksy. Punk hid beneath the office box and waited for an opportunity to tell Lesser some of the truth, but when he remembered the armed guards and the bloodhounds, he made as mild a protest as possible. The company entertained Lesser, and Lesser later informed the German Immigration Society that the men from New York were a lot of “hobos and thieves.”

To hide evidence of abuse, Eugene P. Newlander took Punk and Orminksy away in a horse and buggy. He drove them to a point twenty miles from the camp. There they met Huggins an hour after midnight. Punk was bareheaded—his clothing was scant and ragged. Huggins gave him an old straw hat for the journey. Later Huggins received orders to get the boys some overalls and undershirts.)

They drove thirty-five miles through the pines until they arrived at a rail station. There they boarded a train for Albany, Georgia. The boys began to inquire about pay.

“Youse people owe me $15,” Punk said. “Why don’t youse pay me?”

Huggins assured him that it was all right.

Then they took a train for Broxton, Georgia, where they stayed in the home of Huggins for two days. Then they were taken to Hazlehurst, Georgia. All the time Punk felt that Huggins wanted to “get rid of them.” Huggins overheard Punk expressing this opinion to Orminksy and shook him for it. This gave the boy another opportunity to ask for money.

“You walk with me, or you walk back to Lockhart!” Huggins said. Then he gave them a dollar and left them for the afternoon. “If yer asked where yer goin,’” said Huggins, “tell ‘em yer goin’ th’ mountains for yer health!” (Punk bought candy and soda and gave the remaining ten cents back to Huggins.) From Hazlehurst they went took to Lumber City, where Huggins deserted them.

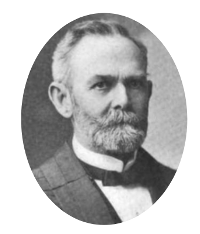

Commissioner F.W. Marsh.[21]

Towards the middle of July (1906,) a prominent citizen of Pensacola witnessed the “capture and return” of a peon and voiced his concern to Commissioner F.W. Marsh of the Federal Court. By this point McGinnis (along with fellow laborers, William Keller, Joseph Davis. Harry Lyman, and Louis Abrahams) had escaped. They told the authorities of the brutal treatment.[22] On July 23, 1906, there an official hearing at which the escaped peons and Eric Von Axelson (Mayor of Laurel Hill, Florida,) testified.[23]

W.S. Harlan.[24]

Around the same time The Pensacola Journal published a story “Inhumanity and Cruelty in Alabama Lumber Camp,” about an escaped peon who was found dying in the streets. The brought forth an angry epistle from W.S. Harlan, the general manager of the company, which resulted in a newspaper controversy.[25] The result of the hearing was a group of indictments by the grand jury and a trial before Judge Charles Swayne.

~

In September 1906, after three months at camp, Lanniger decided to leave. In the company of a few other men, he made his escape. The party was overtaken by one of bosses, C.C. Hilton, the next day. While his companions managed to flee, Lanniger was coerced into staying when Hilton pointed a revolver at him. Lanniger was ordered to walk in front of a horseman to the nearest town, where Hilton gave him in charge of a blacksmith. Hilton took off his belt and revolver and handed them the blacksmith with instructions relating to the Lanniger. After dinner Hilton took his captive to the station where he was handed over to another boss, Solomon E. Huggins, who took him back to Lockhart. After an interview with the manager, Lanniger was driven out to the logging camp, where he was locked up for the night. The following day he was returned to the turpentine camp.[26]

Manual Yordanov.[27]

Corporal punishment became the order of the camp. Men tried to run away and were tracked with bloodhounds and returned. Many of them were tied to trees and flogged. A particularly barbaric episode during this time was the battering of a man named Yordanov. Gallagher beat him with the butt end of a revolver until he fell to the floor of the box car. Gallagher then kicked him in the head until he was nearly killed.

In November 1906 Lanniger escaped once again. Unable to reach Pensacola, Lanniger was forced to return. By this point, several of the men had gone to Mobile, Alabama, to wire an appeal to the Hungarian Consulate at Washington, D.C. A representative of the Consulate investigated the matter, and Lanniger was freed.[28]

~

The next event was the special jury trial on November 15, 1906. For this the prosecution wanted the testimony of Punk and Orminksy.

After Huggins abandoned the boys In Lumber City, they attended a “show” given by a patent medicine company. Punk was particularly drawn to the “doctor.” He had a kindly face, could tell a good story, and his business in life seemed to the boys the purest philanthropy ever seen. He could cure any ill that flesh acquired. Punk thought him a wonder, so he unburdened his heart to him. The medicine man diagnosed the case at a glance and prescribed a remedy—the town marshal. The marshal took notes, and Punk joined the show and went to the next village as one of the staff. His experience as a show man was short-lived, however. He “did” only three towns, then he returned to Lumber City. “Them notes th’ marshal took,” Puck said, “kinda interested me.” He was to communicate with Washington, and the name had a dash of romance for the boy.

Punk then got a job in Hensen’s sawmill, where he was promised $1.25 a day and got $1. He bought some clothes and went back to Hazlethurst. There he found work in a livery stable as a driver. This lasted but a few days. With the independence that a few dollars gave him, he went to Brooklyn, Georgia. (He liked the name. “It sounded near New York.”)

Meanwhile, Secret Service men found Orminsky at Lumber City. Through him they traced Punk to Hazlehurst, where for nine days he remained in jail awaiting the convenience of the Government. Punk and Orminsky were taken to Pensacola as Government witnesses against the Jackson Lumber Company. For some weeks they watched the “whipping boss,” the “bull of the woods,” and others, stand trial.

The officials (the minor officials only, of course) of the Jackson Lumber Company were tried in installments. In his opening charges laid before the jury during the first trial, Judge Swayne stated:

The defendants, W.S. Harlan, S.E. Huggins, and C.C. Hilton are indicted and on trial before you for a violation of the statutes of the United States with reference to peonage. They are indicted for conspiracy to arrest one Rudolf Lanniger with the intent that he should be returned to a condition of peonage—that is to say, to compulsory service of the Jackson Lumber Company, a corporation, to work out an indebtedness alleged to be due by him to the company, and that in furtherance of said conspiracy, and for the purpose of effecting the same, the said C.C. Hilton did by threats and force, within the northern district of Florida and within the jurisdiction of this court, arrest the said Rudolf Lanniger and restrain him of his liberty.

Punk and Orminsky told their stories. The jury returned a verdict of guilty. Six of the bosses —Hilton, Huggins, Harlan, Gallagher, Grace, and Sandor—were sentenced to prison; Gallagher for fifteen months, Harlan for eighteen months, and the others for thirteen months, all with fines ranging from $1,000 to $5,000. Bellinger escaped. Sandor got a year in prison for being in the company of Grace, and Gallagher when they forced Trurich back to work out a debt.

Judge Charles Swayne.[29]

After the trial the peons stood by each other until all were down at the same dead level of poverty. Punk found a job on a square-rigged Norwegian ship called the Hereford that was bound for Buenos Aires in March 1907.[30]

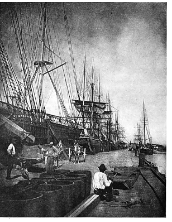

Pensacola Wharves.[31]

~

Towards the end of January 1907, Irvine was invited to Pensacola to stay as the guest of Lewis Van Winkle (a Superintendent of the American Life Insurance Company) in his home on East Jackson Street.[32] Two of Irvine’s fellow passengers to Pensacola were John Le Maistre, the “turpentine boss” of the Jackson Lumber Company and Oscar Sandor. Irvine introduced himself to Le Maistre, who freely entered into discussion of company’s affairs.

After the trial, Irvine learned, an appeal was taken to a higher court. The officials went out on bonds. Sandor, meanwhile, “was shouldered out of the company.” Sandow, now awakened to the fact that, having done the company’s bidding, and getting jailed for it, the company had no further use for him. (Newlander, his friend, and fellow countryman had been similarly dealt with.) So, Sandor was traveling to Pensacola to surrender himself to the court and ask to be sent to prison and fulfill his sentence.[33]

While in Pensacola Irvine made a visit to the city jail and asked permission to address the prisoners. The jailer, of course, wanted to know what an unkempt laborer had to say to his charges. In order to convince him, Irvine was compelled to deliver an exegesis before the desk.

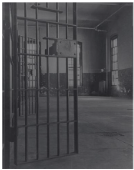

Old Escambia County Jail. (Source: Pensacola Museum of Art.)

A young Englishman, who had landed after a long sea voyage the night before, was the first man Irvine spoke with. The Englishman claimed to have been drugged and robbed in a saloon. The fact of his incarceration was a small thing to him; what made him swear was the condition of his cage. (The cells were iron cages with stone floors.) “Look!” he said, pointing to the excrement of half a dozen of his predecessors in various states of fossilization. It laid all around him in the cell, nauseating and suffocating him. Fire shot from the Englishman’s eyes; he was bitter, sarcastic, sneering, and had every right to be. The discourse on Socialism which Irvine had planned was driven from his mind. Irvine became determined to work out a plan by which he could help Pensacola to “clean up this social ulcer.”

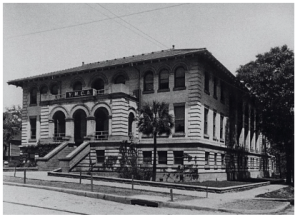

Escambia County Courthouse, Pensacola, Florida. (c/o) Florida Memory.[34]

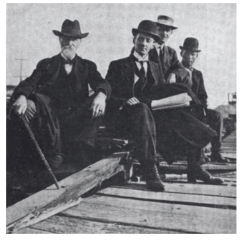

On January 22 Sandor was sentenced by Judge Swayne. Owing to his cooperation, however, Sandor was allowed to walk about the streets during the afternoon with the escort of Deputy Marshall Ray. Newlander and Irvine met him at the courtroom after the sentencing.

(Left to Right) Eugene P. Newlander, Oscar Sandor, Deputy Ray, Mikhail Trudich.

“Well,” said Sandor, “as much as anyone dislikes to go to jail, I prefer the Atlanta prison to Lockhart. I went before the court this morning and voluntarily surrendered, and the judge reduced my sentence from thirteen months to one year and one day and remitted my fine. I am going to stop here only a day. I intend on going to Atlanta to start serving my sentence of thirteen months. I have ambitions and have a chance to go to England and better myself. I know those people at Lockhart will have to go to Atlanta before the end, so I decided to come and start mine now. I shall write home to Hungary and tell my people how a stranger, who has unwittingly disobeyed the laws of the United States, has been treated.”[35]

While walking along the sidewalk, they came upon Trurich and Yordanov who just so happened to have a day’s leave of absence. At Irvine’s suggestion they went into a café, to discuss the events of the previous summer over a cup of coffee. It was by participating in the kidnapping of Trurich which landed Sandor a year in prison, but they were as friendly now as though they had been brothers-in-arms. Yordanov kept his eye on the clock. When it was time to go, he stood erect with hat in hand to say goodbye. The boat would convey the peons back to their jobs on Fort Pickens was almost due.

The Escambia Hotel. (Source: Florida Memory.)[36]

That night Irvine accompanied Sandor to the parlors of the Escambia Hotel, the place where he was staying. Sandor and Newlander unburdened themselves, and Irvine related his experience as a teamster in the camp.

“Why didn’t you await the result of appeal?” Irvine asked.

“I prefer to await it in the penitentiary,” Sandor replied.

“Isn’t this a change of mind,”

“Yes, it is.”

“When did this change occur?”

“Immediately after the trial,” he said. “I saw that it was impossible to longer with the company. I was sick of shams. I had played a part in a concern, and I was anxious to get away!”

“What do you mean by ‘dishonest.’ Were they dishonest in business?” Irvine asked.

“We were dishonest in our treatment the men. We had a system of labor which we gave out at the close of the day. In so many hundreds of men it frequently, of course, that men forgot to get the check for the day’s work. If a man did so, the chances of his getting it later were very slim. We had an understanding about it in the office. If he stoutly persisted, we had to give him what belonged to him, but I have collected as many as 700 days’ labor in one month. We might as well have put our hands into men’s pockets and extracted from each of the 700 men, the price of a day’s labor. Our system of monthly payment was another source of revenue. Of the hundreds of men in our employ, very few could stretch over the month without borrowing. Of course, it was their own they were borrowing, but we charged them ten percent. Another source of revenue was our insurance; we insured all our employees for our own benefit. We made $300 a month out of them by a medical tax. This sum was net after paying a physician.

“In our store we made from fifty to a hundred percent on our goods, and in it we had our own currency for change, so that the people would have to come back to spend it. All of this was merely business. I thought the limit was reached when I was called a coward for refusing to ride on an expired railroad pass on the company’s business; but it was not. It came on a summer’s evening when a few of us officials sat outside the office on the steps. We were discussing the escape of several laborers when again I, with others, was called a coward—not because we lacked commercial acumen, but because we had not shot down like dogs in the forest those helpless, fleeing men. That is the spirit of Harlan; and Harlan is the soul of the business at Lockhart.”[37]

~

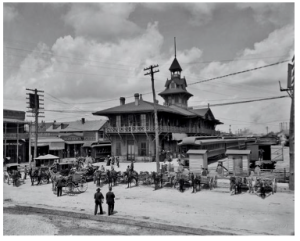

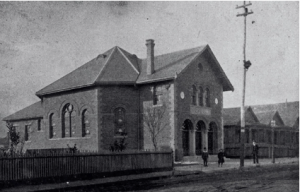

Louisville & Nashville Railroad Depot on Tarragona Street.

The day after Sandor left for Atlanta, Irvine, and J.H. Sherrill of the Y.M.C.A., delivered short addresses at the shops of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. A large number of workers were in attendance.[38] Irvine met members of a Tourist Club and offered to lecture for them. It was arranged for the following Sunday afternoon. With the connections he had made, Irvine was able to call on the mayor of Pensacola, Charles Henry Bliss, who promised to preside.

Pensacola Y.M.C.A. (Source: Wikipedia)

Irvine delivered two addresses on Sunday January 27, 1906. The first was at the Y.M.C.A. where he lectured to a gathering of considerable size. The second lecture, “Universal Brotherhood,” was for the Tourist Club at the Universalist Church on 47 East Chase Street. He lectured for forty minutes on his experiences as a laborer in the camps of the South, and for ten minutes at the close he described what he had seen in the Pensacola Jail.

Temple Beth El (37 East Chase Street. Near the Universalist Church.) (Source: Pensacola News Journal.)

“I have recently visited the place where prisoners are confined here,” said Irvine. “I have looked into the manner in which they are cared for by the city. I have traveled four countries, one of them being Russia, and I have never seen anything so debased and degrading as the conditions that prevail in the jail of Pensacola. They are horrible.” Continuing on the theme of “Universal Brotherhood,” Irvine next turned his attention to the cause of wealth disparity. “Economic conditions are the governing forces in society,” said Irvine. “The system rather than the individuals is to blame for much of the poverty and misery of the present.”

Charles Henry Bliss.

Mayor Bliss followed Irvine in a very forceful address on the same theme. “I abhor the use of so much wealth in the building and maintenance of the equipage of war. I believe that we will yet all be brothers and so administer our affairs that war and poverty and preventable disease will be banished from this earth.”[39]

It was a somewhat drastic method of treatment, and though Irvine did not remain long enough to see the effect, he at least deprived the municipality of the plea of ignorance. Irvine left Pensacola on January 29, 1907, for Montgomery, Alabama.[40] From there he would return to New York for the next phase of his work.[41]

PEOPLE OF THE UNDERWORLD

I. INTERCOLLEGIATE SOCIALIST SOCIETY.

II. THE CRY OF PEONAGE.

III. MUCKERS.

IV. GALLAGHER’S HELL.

V. PUNK.

SOURCES:

[1] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life in Peonage: Part III: The Kidnapping Of ‘Punk.’” Appleton’s Magazine Vol. X, No. 2. (August 1907): 190-1

[2] “Russian Revolutionist Talks.” The Record-Journal. (Meriden, Connecticut) May 28, 1906; “Rev. Alexander F. Irvine.” The Morning Journal-Courier. (New Haven, Connecticut.) August 16, 1906.

[3] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life In Peonage.” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 6. (June 1907): 644-654

[4] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life In Peonage.” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 6. (June 1907): 644-654

[5] Manhattan’s “Little Italy” was a neighborhood bounded by Third Avenue and the East River between 100th and 120th Streets. [Grieveson, Lee; Krämer, Peter. The Silent Cinema Reader. Routledge. London, England. (2004): 122-123.]

[6] New York (N.Y.). Tenement House Dept. Report of the Tenement House Department of the City of New York (1907-1908). Martin B. Brown. New York, New York. (1908): 44.

[7] Hart, Hastings H. Cottage and Congregant Institutions. Charities Publication Committee. New York, New York. (1910): 48.

[8] Munch, Janet Butler. “At Home in the Bronx: Children of the New York Catholic Protectory 1865-1938,” The Bronx Country Historical Society Journal. Vol. LII, No. 1-2 (Spring 2015): 30-48.

[9] New York State Board of Welfare. Proceedings of the New York State Conference of Charities and Correction. J.B. Lyon Company. Albany, New York. (1903): 303; New York State Board of Welfare. Annual Report of the State Board of Charities for the Year 1913: Vol. II. J.B. Lyon Company. Albany, New York. (1914): 764-765.

[10] Salm, Luke. “Brothers of the Christian Schools.” Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice. Vol. XI, No. 2. (December 2007): 188-197.

[11] “About Slang.” The Buffalo Enquirer. (Buffalo, New York) August 29, 1903.

[12] “A Dictionary of Can’t Terms Compiled by ‘Strong-Arm’ Men.” The Birmingham News. (Birmingham, Alabama) October 1, 1904.

[13] Zimmerman, Jonathan. “Simplified Spelling and the Cult of Efficiency in the ‘Progressiv’ Era.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Vol. IX, No. 3 (July 2010): 365-394.

[14] “New Slang.” The Carbondale Daily News. (Carbondale, Pennsylvania) May 7, 1903; “Strange Under World Speech.” The Shreveport Times. (Shreveport, Louisiana) March 4, 1904.

[15] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life in Peonage: Part III: The Kidnapping Of ‘Punk.’” Appleton’s Magazine Vol. X, No. 2. (August 1907): 190-197.

[16] “Horrible Conditions Described by Witnesses.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) July 31, 1906.

[17] “Horrible Conditions Described by Witnesses.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) July 31, 1906.

[18] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life in Peonage.” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 6. (June 1907): 644-654

[19] “Horrible Conditions Described by Witnesses.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) July 31, 1906.

[20] “Horrible Conditions Described by Witnesses.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) July 31, 1906.

[21] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life in Peonage.” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 6. (June 1907): 644-654

[22] “Horrible Conditions Described by Witnesses.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) July 31, 1906.

[23] “Horrible Conditions Described by Witnesses.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) July 31, 1906.

[24] “Conviction on Peonage Charges Secured Upon Dubious Testimony.” The American Lumberman. No. 1666. (April 27, 1907): 39-40.

[25] “Inhumanity and Cruelty in Alabama Lumber Camp.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) July 24, 1906.

[26] “Judge Swayne is Severe on Habitual Pistol Toters.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) November 16, 1906; “The Central South: From Alabama’s Capital.” The American Lumberman. No. 1644. (November 24, 1906): 87.

[27] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life in Peonage.” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 6. (June 1907): 644-654

[28] “Judge Swayne is Severe on Habitual Pistol Toters.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) November 16, 1906; “The Central South: From Alabama’s Capital.” The American Lumberman. No. 1644. (November 24, 1906): 87.

[29] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life in Peonage.” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 6. (June 1907): 644-654

[30] “Three of Crew Were Lost.” The Chattanooga Daily Times. (Chattanooga, Tennessee) April 9, 1907; “Story of the Wreck of Norwegian Bark Hereford.” The Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) April 16, 1907.

[31] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life in Peonage: Part III: The Kidnapping Of ‘Punk.’” Appleton’s Magazine Vol. X, No. 2. (August 1907): 190-197.

[32] R.L. Polk & Co.’s Pensacola Directory: Vol. III. R.L. Polk & Co. Publishers. Pensacola, Florida. (1907): 298;“Alex Irvine Will Speak.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 6, 1907; “Rev. Alexander Irvine Leaves for Montgomery.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 30, 1907; “Tersely Told.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 7, 1909.

[33] “Oscar Sandor Surrenders to the U.S. Authorities.” The Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 23, 1907.

[34] Escambia County Courthouse & Armory. Pensacola, Florida. Florida Memory. State Library and Archives of Florida.

[35] “Oscar Sandor Surrenders to the U.S. Authorities.” The Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 23, 1907; “Oscar Sandor Before U.S. Court.” The Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 24, 1907.

[36] Escambia Hotel. Pensacola, Florida. Florida Memory. State Library and Archives of Florida.

[37] Irvine, Alexander. “My Life in Peonage: Part II: A Week With The ‘Bull Of The Wood.’” Appleton’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 1. (July 1907): 3-15.

[38] “Meeting at the Shops of the L.&N.” The Pensacola News Journal. (Pensacola, Florida) January 25, 1907.

[39] “At The Y.M.C.A. This Afternoon.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 27, 1907. “Rev. Irvine Delivers Two Addresses Sunday.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 29, 1907.

[40] “Rev. Alexander Irvine Leaves for Montgomery.” Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) January 30, 1907.

[41] Irvine, Alexander.” From the Bottom Up: The Life Story of Alexander Irvine. Gosset & Dunlop. New York, New York (1910): 271-273.