The premise is simple: read one comic every day for the entire year. It seems like a simple task but there is no way that I read 365 comics last year, even if you count the individual issues in collections. So, this year, I am committing myself to this reading challenge, in the hope that I can broaden my reading habits and fully engage with my favorite hobby again.

Last week felt a bit intense, but I definitely enjoyed getting my teeth into some comics with monstrous characters. I thought I’d have an easier week this week — keep it light with some laid back reading. Catch up on some of the series I’ve started but not finished, revisit some old favorites, and play it by ear.

So, without further ado..

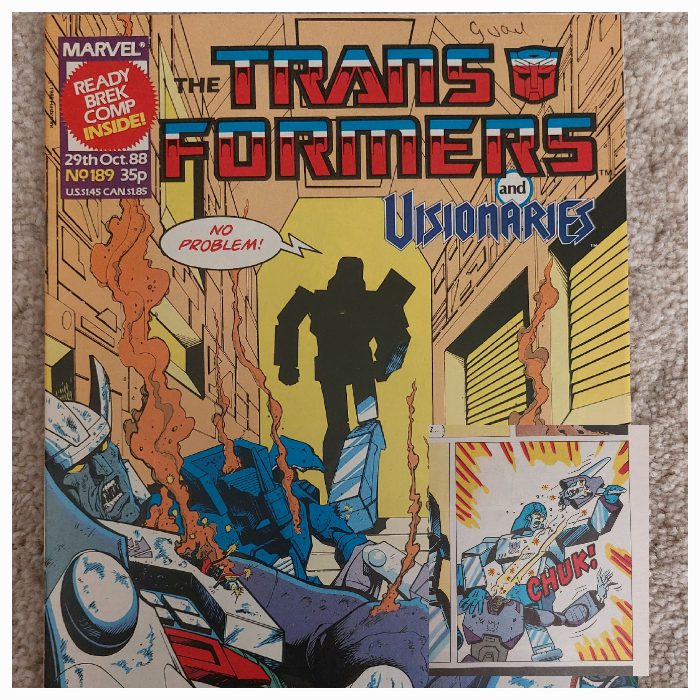

Credit: Marvel UK.

Comic Number 127: The Transformers #189

So, I failed to reach issue 200 before the end of April, but I am so close now. In fact, this issue plays a very important role in setting up the story that features in issue 200.

Dry Run, by Simon Furman, Dan Abnett, and Jeff Anderson, is a simple, stand-alone story involving the current leader of the Decepticons training the former leader of the Decepticons to kill the future leader of the Decepticons. Simple…

Jeff Anderson’s pencils breathe life into the rage filled robots and gives them an animation that is lacking in some of the earlier stories. The emphasis in the art is on the conflict between the different factions of Decepticons, and once the story gets underway, there is virtually no background detail. Anger and unbridled hatred fuel the characters and the artwork focuses on this and nothing else.

The crux of the story, and the important moment, comes when an enraged Megatron tears the head off Cyclonus. A pivotal moment that is punctuated with a panel at the bottom of the page hinting at the consequences of the action.

What is fascinating about this moment is its brutality. It is easy to forget that these robots are sentient beings with a spark of life. Throughout most of the comics the Transformers fight, get injured and reappear fighting fit a few issues later or disappear from the roster of characters. Other than the death of lead figures, the violence between the warring robots is cartoonish: ineffectual but visually exciting. This is a children’s comic after all. But the death of Cyclonus is more unsettling and glimpses at the disturbing truth about war and violence. Megatron is blinded by hatred, silent in his action which is a contrast to the constant commentary throughout the rest of the battle. The violence of the moment brings the reader to a dead stop. The final panel on the page, which sets up the consequences of the action, also acts as a palette cleanser for the scene. The reader is removed from the violent scene for a moment so that they can process what they have witnessed.

I keep thinking what the scene would look like if the two characters were people and not giant, transforming robots. You’d be looking at something Garth Ennis might have written.

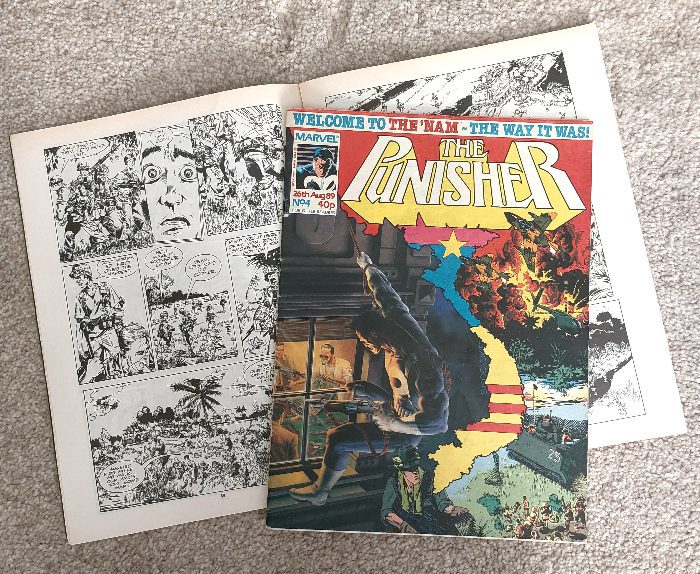

Credit: Marvel UK

Comic Number 128: The ‘Nam (in The Punisher #4, 5, 6 and 7)

Keep it light was the plan so why not re-read some of Marvel’s The ‘Nam, an intense war comic based (roughly) on the experiences of real veterans of the Vietnam War?

When Marvel and DC produced their early war comics, they glorified war and those who fought in them. Later comics would buck this trend and create a more authentic feel for the soldiers’ experience, shifting the focus from physical violence towards a psychological onslaught against the mind. The emphasis of war trauma moved focus and The ‘Nam was part of that shift.

In 1989, Marvel UK began publishing The Punisher, reprinting stories from the American version, in a similar fashion to The Transformers comic. Each issue came with a backup story and the first three issues contained the adaptation of Robocop. But from issue 4 onward, they introduced a black and white reprint of The ‘Nam. Written by Doug Murray and drawn by Michael Golden with Armando Gill on inks, The ‘Nam told the story of new recruit, Ed Marks, as he shipped out to Southeast Asia. The first story, Nam: First Patrol was printed over two issues of The Punisher and contained a crash course in the military action set mostly in the jungle. There is a lack of national politics in the narrative, but military politics is introduced fairly early on with Ed completely failing to realize that certain elements of the American Army were taking bribes for cushy postings.

The artwork captures the hectic day-to-day life of a newbie in the American army. The controlled line work keeps the action readable, even when the situation is out of control, and the cast are exaggerated enough to give them character but not too much that they become parodies or stereotypes.

Doug Murray uses the new recruit as a way to draw the reader into the story, allowing the audience to learn as the character learns. It also provides a certain leeway into explaining elements of army life within the narrative because Ed needs to learn as much as the reader does.

Using Ed Marks as a focal point of the narrative allows this gateway in for readers but does restrict a larger examination of the Vietnam conflict. Harriet E. Earle explained in A New Face for an Old Fight that early representations of war, and the Vietnam war in particular, had a focus that was “firmly on the military conflict and Vietnam as a theatre of war, without nuance of the country itself.” (pg 90 Studies in Comics Vol 9 No 1 2018) This is an argument that can be made in relation to the early issues of The ‘Nam, with the country and its people nothing more than setting for the story of Americans. As the series goes on, I believe that this did change and the wider narrative grew, but here, at the beginning, these “comics are snapshots of the immediate moment, of the military task at hand.” (Earle, pg 91)

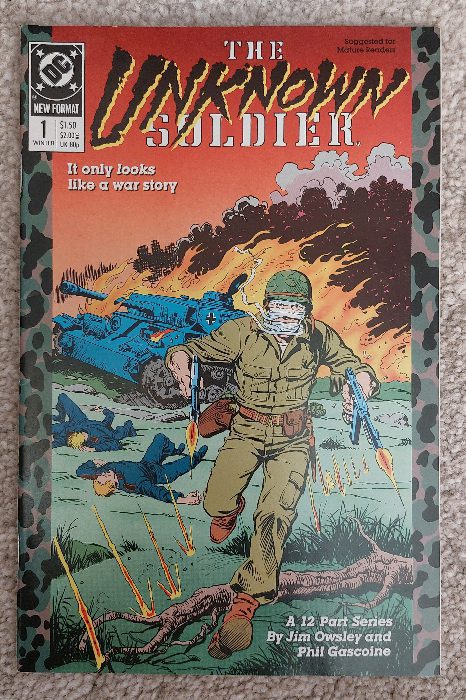

Comic Number 129: The Unknown Soldier #1 (1988)

DC’s The Unknown Soldier was, at inception, a contrast to what comics like The ‘Nam were trying to do. Original appearing in Our Army at War in 1966, the lack of identity for the character allowed the possibility for him to become any man, and real life events could be mixed with fictional representations using the Soldier as a bridge between the two.

The decision to set the comic in the past, away from the Vietnam war, gave the creators more liberty to glorify the trauma of conflict and caricature not only the people but the very war itself. It wasn’t until 1988’s 12-part series by James Owsley and Phil Gascoine that mental trauma would become more important in the comic’s story line than the physical injury from violence.

DC’s 1988 The Unknown Soldier took the concept of the Unknown Soldier in a new direction and tackled head on the brutality and politics of war as an idea, not a setting. The first issue carries the tagline ‘It only looks like a war story’ over an illustration of the eponymous hero with his bandages unfurling as he runs towards the reader, firing his weapons. Behind him a German tank burns with its crew spread, lifeless, on the ground around it. The cover is misleading as only three pages of the story inside feature the Second World War and the enemy the soldier faces is mental deterioration not physical trauma.

This section of the comic relates back to the origins of the Unknown Soldier from Star Spangled War Stories #154 (1971) but takes a more cynical look at the creation of the character. Instead of fighting his way to freedom in the face of serious disfigurement, in this retelling the Soldier goes directly from injury to hospital. He is not a hero who excels at outstanding deeds, instead it is inferred that he is a failure. His one mission was a promise to his deceased mother to protect his brother, something which he fails to do. The idea that war should not be glorified becomes the backbone of this 12-issue run as the Soldier moves from war zone to war zone doing the dirty work of the government.

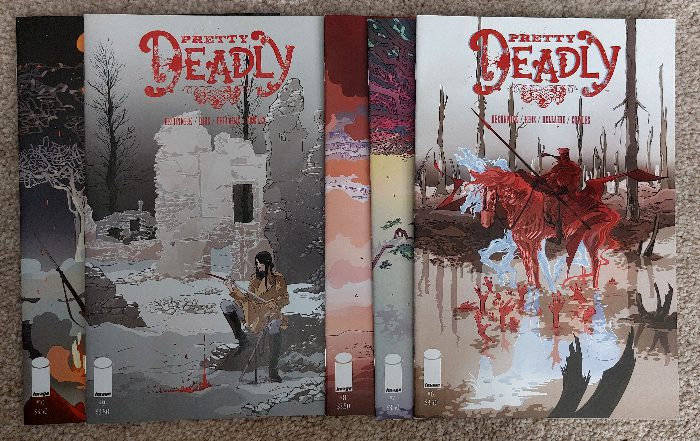

Comic Number 130: Pretty Deadly (Vol 2 ) #9

Changing the theatre of war for this comic, as the third arc of Kelly Sue DeConnick and Emma Rios’ Pretty Deadly is set during the First World War. The arc, which started in issue 6, revolves around the Reapers, central characters across the series, traveling to the trenches of France to find and safeguard one young soldier, Cyrus, so that he might return home before his mother passes away.

Scenes throughout the arc superbly capture the psychological trauma and desolation of the war. In an early scene of issue 7, Sissy tells Foxy of her visions of Cyrus and that he has “Dug himself a grave as far away from home as he could get.” The speech leads into a dark image of a soldier, hunched over with shadowed hands reaching across him. A few pages later, the reader is forced to climb into the trenches with the soldiers as the scene is broken down into a number of panels, with the boxed rooms of the trench creating natural panels for the reader to traverse. Rios covers her pages with numerous panels without over complicating or confusing the images. Small snippets of rolling dice or rat whiskers lend as much to the narrative as the open desolate shots of no-man’s land. Rios captures the landscape and uses the visuals to enhance the metaphors laid out in the script.

But it is issue 9 that contains the most interesting representation of war, or rather the theatre of war as a backdrop for a narrative. Part of the narrative revolves around two reapers, Ginny and Big Alice, as they try to stop the war. They face the Reaper of War on the battlefield and their fight is symbolic of the larger conflict that is happening behind and around them. The big reveal, towards the end of the issue, is that the Reaper of War does not work alone, and the horse that War rides is the Reaper of Fear.

It is a powerful comic that that faces the concept of war head on. The focus is split between an individual and the larger scale theatre of war. DeConnick and Rios use the narrative to highlight each aspect and how the fear and relentlessness of the greater conflict can destroy the individual.

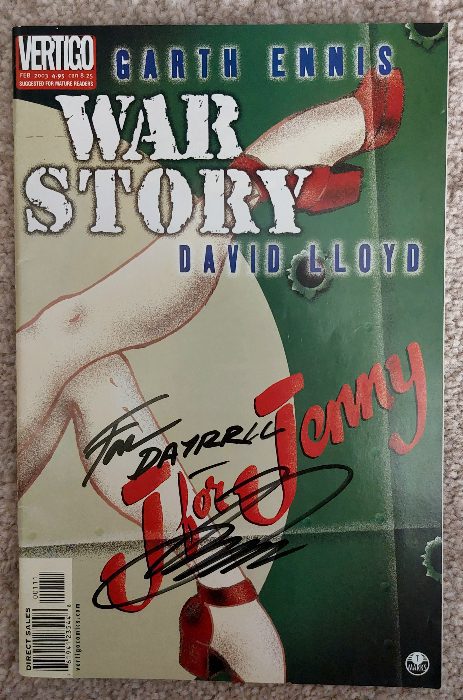

Comic Number 131: War Story: J for Jenny

I mentioned Garth Ennis earlier in the week and, if you know his work, it would come as no surprise that he’s written a number of war based stories. Not only did he write specific war based series, such as Battlefeild, but he also worked on a four issue reboot of Unknown Soldier, which I nearly picked up this week. One for the future.

Ennis is well known for writing tough, no-nonsense characters and excels at facing offensive material head on. You can expect violence, bad language, and characters with strong, conflicting opinions. J for Jenny is no different and, in fact, it forms the heart of the narrative.

The comic follows a crew of a British bomber on several missions during the Second World War. Tensions between the pilot and the co-pilot build as their differing views on the war put them at loggerheads. On the one hand you have Page, the pilot, who is gung-ho and, due to the traumatic experience of losing his own family, doesn’t seem to have any care for the consequences of their bombing raids. Do the mission, get home would be his mantra. If there are civilian casualties, so be it.

Contrasting this viewpoint is the co-pilot Thomas Stark who believes there has to be a better way to destroy the enemy without civilian casualties. At one point, he talks about using his inheritance to fund a charity to help those affected by the war.

On the surface, it’s a good versus evil story, but as the narrative unfolds, Ennis gives us the personal views of each crew member of the bomber and in doing so reveals a whole lot of gray. Each character is struggling to come to terms with the war and their role in it. They each want or expect something different from their life and even the two central characters are shown to be more complex than simply being right or wrong. J for Jenny is an examination of the mentality of war disguised as a Boys Own adventure story.

The artwork by David Lloyd does a lot of the heavy lifting at depicting the atrocities inflicted on and by the crew of the bomber. Their arguments and internal thoughts are posted to a backdrop of murky skies, chaotic fights, and flashes of destruction. Lloyd’s work has the fog of war seeping onto every page and his coloring reinforces Ennis’ main theme: the grayness between right and wrong.

J for Jenny is a thought provoking treatise of a war story which only occasionally becomes ham fisted with the points it wishes to make.

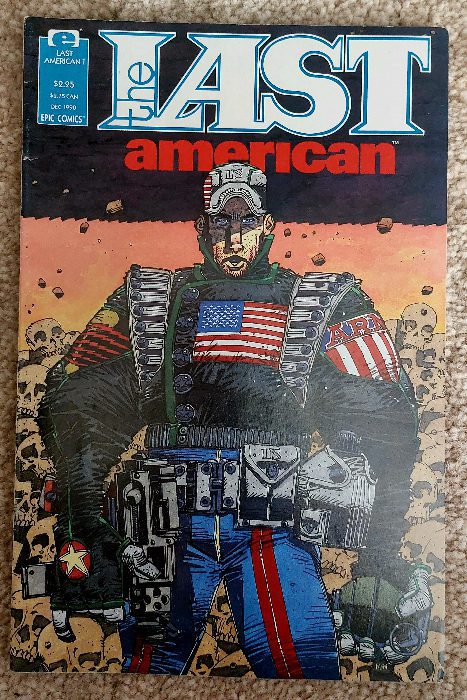

Comic Number 132: The Last American #1

In December 1990, the first issue of The Last American was released by Epic Comics. The story was bleak, hopeless, and distressing on a number of levels. However, the script by Alan Grant and John Wagner was beautifully illustrated by Michael McMahon who was beginning to perfect his own, unique style of drawing.

The comic tells the story of Ulysses S Pilgrim, the last American of the title, as he wakes 20 years after a nuclear war to emerge into a landscape of destruction and desolation. He has three robotic sidekicks and a slowly dissolving grip on reality. In essence, The Last American examines the effects of loneliness and hopelessness on the human mind — a mind raised on the American Dream.

McMahon’s artwork is the star of this comic. His cubist style with thick black lines and harsh shadows creates a world that is often abstract and divorced from reality. Just like the central character trying to come to terms with his surroundings, it is difficult to get a firm footing in McMahon’s visuals. Panel transitions are erratic, jumping from the characters to the destruction around them to quick memory flashes. The amount of panels dominated by skulls constantly reinforces the concept of death that inhabits every element of the comic. In the Solrad review of The Last American, Tom Shapira points out that the true horror of the comic is “not just death of the self, or even death of the many, but the sense of utter annihilation, the notion that nothing we do will have any meaning in the end.”

And this is a universal fear: the fear of being forgotten, of being meaningless. A lot of war narratives have this theme running through them, often hidden underneath the violence and the action. The gung-ho characters and cartoonish villains are all spurred on by the idea that to become a war hero will grant them some ever lasting life. A purpose to be remembered for. The Last American challenges that idea, showing the reader that random pop cultural items are all that remains for whoever survives.

That and the ants, apparently.

Comic Number 133: Transformers #199 – 205 (the Time Wars story line)

I wanted an easy week of reading this week, but somehow managed to surround myself with war comics and trauma. So to finish off, I’ve finally reached the 200th issue of Transformers (UK edition) that brings to an end (sort of) Simon Furman’s “future era” storyline that began way back in issue 78. The story is, for the most part, all-out action as Autobot fights Decepticon, Autobot fights Future Autobot, Decepticon and Autobot fight other Decepticons, and Future and present Autobots team with present and future Decepticons to fight Galvatron.

Furman includes a number of elements that have featured across the entire saga, including the limbo world where the displaced Transformers end up when time travel is involved. He collects all of the dangling threads and ties them off, one by one, to bring everything to a satisfying close. Plus, for issue 200, he brings back Ravage, one of the more exciting and interesting Transformers.

The artwork is provided by Robin Smith and Lee Sullivan whose styles define this era of the comic in the UK. It is fluid and dynamic, giving the giant robots an organic presence that contrasts the rigid, mechanical look of the American comic. As a result, the characters are more empathetic or even human-esq which gives the narrative an emotional punch I find lacking from some of the stories.

It is also a “save the universe” style story full of sacrifice and heroics and devastating loss. The risks are high because there is all to play for. In retrospect, Time Wars has more in common with the early propaganda style war stories, focusing on the good versus evil and the heroics of the characters rather than the actual theatre of war. Within this story, four planets are under threat of extinction and yet that devastation barely features.

But, for a story line 122 issues in the making, it is everything the reader would want. Carnage and resolution.