Baseball teams have long provided a means for youths growing up in rural areas to remain active in the summer months and often served as a point of pride for many small towns.

In the years following World War II, the community of Enon in Moniteau County had a rustic baseball diamond used by local youths to hone their skills and, in one instance, resulted in an accident that has become a highlight of spirited retellings.

“We played on the ball diamond south of Enon, and it was really a terrible field, especially compared to the fields you see these days,” Don Wyss said. “It was just an old pasture that was full of rocks and if you weren’t careful, a ball would be hit toward you, and it might glance off a rock and strike you in the face if you weren’t paying attention.”

Wyss said he often played shortstop for the Enon team that, despite being in Moniteau County, often played against teams in the adjoining counties and were part of the Miller County Baseball League.

An article appearing in the Miller County Autogram on July 6, 1950, noted the Enon league included such communities as Brumley, Ulman, Henley, Olean, Lake Ozark, Eugene, Mary’s Home, Tuscumbia, Hickory Hill and St. Elizabeth.

An area newspaper advertised that as early as 1909, Enon boys were gathering on the ball field south of town to participate in America’s national pastime. A little more than a decade later, the field remained a point of interest for the community and there were often enough players available to field two separate teams.

“The Enon ball team had a good game Sunday with Barnett on the Enon field,” noted the Eldon Advertiser on Sept. 1, 1921. “Score 8 to 3 in favor of Enon.” The following year, on April 27, 1922, the newspaper added, “The Enon ball team is rounding into form and will soon be ready to cross bats with opposing teams from the nearby towns.”

The younger players in the area had predecessors whom they admired, such as Ralph Watts, Wyss said. Having come up in the Enon community many years earlier, Watts was said to have possessed legendary pitching abilities and could hurl the baseball with such force that catchers wore extra padding or risked bruising their palms.

“Some the older folks in the Enon area perk up when you talk about baseball,” Wyss said. “It was always said that had Watts been given a little coaching, he could have made the big leagues. In later years, he moved out to the state of California.”

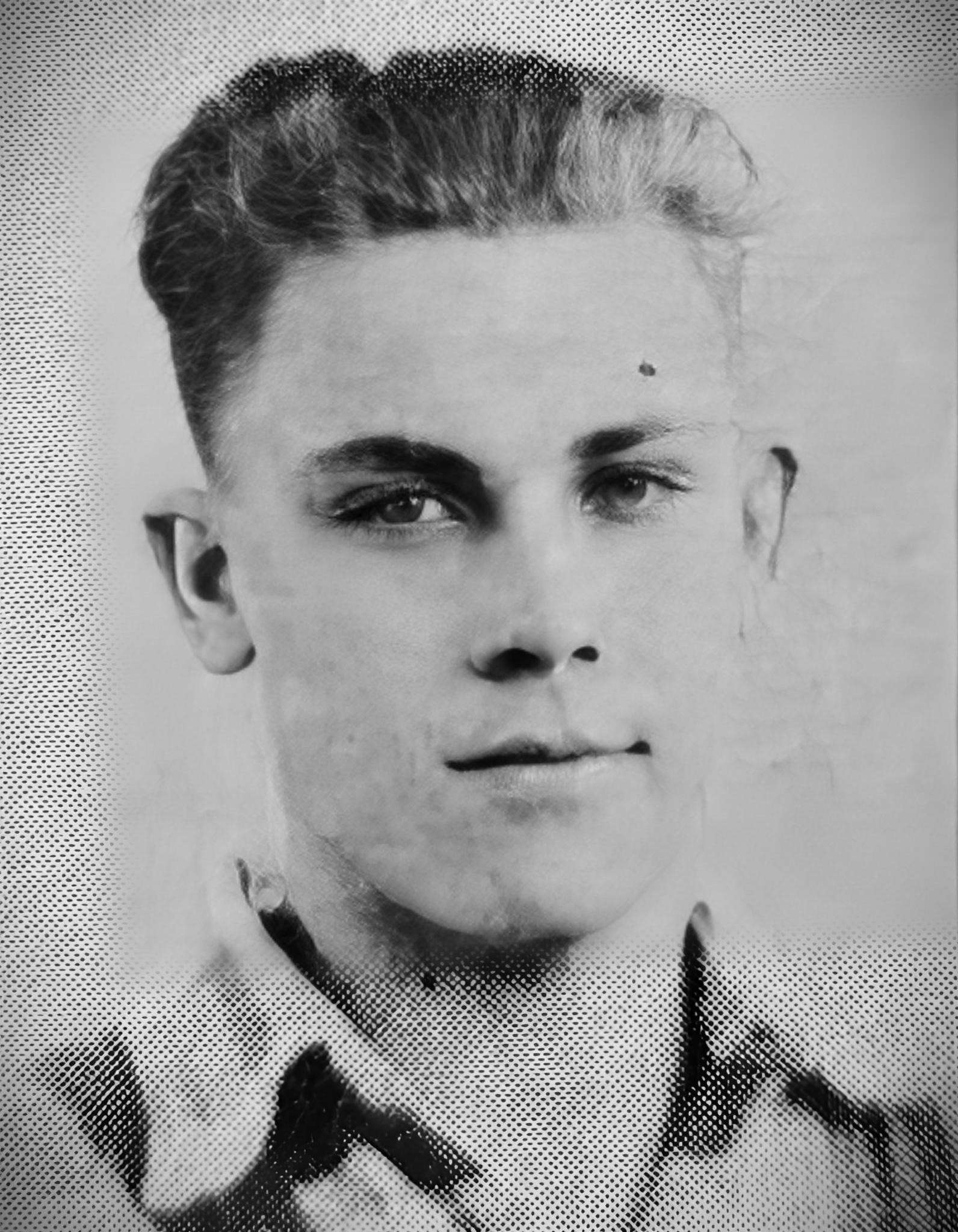

But it was years after Watts’ playing days, when Wyss was a young boy, that a practice game on the Enon ballfield created a memory that has been seared in his memory. Herschel Enloe, who was raised on a farm north of Enon, had just finished his junior year at Russellville High School in 1948. Also on the team was Freddie Miles, a young man from the Scrivner area who was in the same high school class as Enloe.

“A few years before, I had gone to school at Enon School (a one-room schoolhouse) with Herschel and some of the other Enloes,” Wyss said. “The Enloes all seemed to be very good athletes from what I remember. Freddie Miles was always a good athlete, and he pitched for our team.”

Wyss continued, “There were many other good local boys playing on our team, too … like Paul Shikles and Wayne Morrow, and we had games about every week during the summer months.”

It was during this game in the summer of 1948, when a group of Enon gathered to practice on the rough field, that Herschel Enloe volunteered to be the catcher and Freddie Miles the pitcher.

“We told Herschel that you don’t catch without a facemask, but he said, ‘I can do it, I don’t need a mask!'” Wyss recalled.

Winding up for the pitch, Miles hurled a fastball toward their makeshift home plate, and the batter swung, catching the edge of the baseball. The foul ball then moved with both speed and force toward Enloe.

“The ball smacked Herschel right in the mouth and there was blood just pouring down his chin,” Wyss said. “I can still see in my mind him opening his hand and spitting out at least a dozen broken teeth.”

“He bled like a stuck hog,” Wyss firmly added.

Enloe was taken to a dentist and, to this day, wears a dental partial because of a ballgame that occurred more than seven decades ago. Now in his 90s, he has for the past few years resided in a veterans’ home in Illinois. Freddie Miles, along with many of their teammates from that day, have since died.

The story of Enloe’s bloody catching experience, along with Watts’ abilities as a pitcher, are stories that continue to be passed down through generations of Enon residents. The rustic ballfield on which they played is now nothing more than a grassy farm field hemmed by barbed wire fences.

“Nowadays all of the ballfields seem like they are smooth and well-groomed, but we managed to play on that rough pasture field when we were young,” Wyss said. “There were also some rough and tough boys who played the game back in those days, but the Enon ball field sure gave us many good memories.”

Jeremy P. Ämick is the author of “Hidden History of Cole County.”