Charles Mackay’s 1841, titled Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds has enduringly served to refute claims of collective wisdom. He described events like Dutch tulip mania and the 1711-22 South Sea Bubble as frenzies of collective investment hysteria.

In the modern era, every decade or so we have seen more such investment delirium, including the build-up to the 1929 Wall Street crash with lesser events like the 1970s Poseidon mining boom/bust and the 2007 collapse of US leveraged housing funds.

In all cases, investment frenzies ramped up share prices to stratospheric levels. Lessons have not been learned. The next debacle will centre on puncturing the carbuncle of funds focused on virtue signalling their Environment, Social, and Governance credentials (ESG), the apogee for which is fossil-fuel-phobia and renewable-energy-philia.

Collective madness is not confined to money markets. Even before media control hid reality, huge majorities of Germans, Russians, and Chinese willingly supported leaders who were promoters of violence and destroyers of economic stability.

The antidote to unsound business investments is that an accumulation of investors recognises them and sells them. For political malfeasance, such a cleansing is more difficult. Thus, even with an independent media and Parliamentary accountability, a likely majority of US citizens support the obviously corrupt and incompetent President Biden. More parochially, Victorians have sequentially re-elected a Premier who has squandered public funds, including by increasing public service employees by twice as much as other states.

Modern vulnerabilities to political turmoil stem from political hubris in claiming expertise in where the economy’s structure should be heading. Previously, politicians could not credibly claim expertise in the innovations and investments necessary to drive economic growth. The developments that have created the modern economy’s wealth – in transport, automation, energy, health, and communications – took place with little direct political input.

But today’s electorate seems to accept politicians’ claimed expertise in controlling the vital area of energy policy. The genesis of this control started with confected concerns about global warming. These are easily dismissed – there has been no increase in climate emergencies, no increase in hurricanes, no loss of coral, no rise in the oceans, no loss of ice cover, and so on. Blind to such evidence, political measures have been assembled to counteract the phantom threats.

Political leaders ranging from UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to our very own John Pesutto say they concluded they must act after listening to climate sermons from their teenage daughters, which were canalised from teachers in their private schools. This, a fractured thread from climate science to political action, is representative of a broader march of the green left through educational institutions as well as those of media and the civil service.

The susceptibility of politicians to climate hyperbole is heightened as a result of their assigned role to combating it. For the first time outside of war-like conditions, they have an issue that offers them a hero’s role, one far more attractive than buying support by addressing mundane local matter and balancing budgets.

The theme’s potency is much enhanced by the numerous, much publicised international meetings which place the seal of approval to proposals crafted by hand-picked bureaucrats..

Hence, outside of the US there are few politicians who have not bought the narrative. Even Britain’s Conservative Party’s leader-in-waiting, Lord Frost, argues that current policies are ‘hurtling towards Net Zero at any cost’, instead of recognising the energy ‘transition’ to wind/solar as a constantly receding mirage. He says he believes that the UK is simply proceeding towards the renewables ‘transition’ too quickly. For his part, Mr Albanese is linking his own policy to a reinforcement of the American alliance alongside access to US subsidies.

And the thread wends its way throughout national fabrics. Authorities and sloganeers alike are almost unanimous in seeing the elimination of coal as one essential building block of future economic sustainable prosperity.

Even coal company representatives seem to feel obliged to denounce their product, much like terrorised Chinese ‘capitalist roaders’ facing Red Guards and wearing dunces caps. In its Annual Report the coal miner Whitehaven acquiesces in the death of coal, claiming it supports the Paris Agreement’s aims of limiting global temperature rises to well below 2 degrees, the corollary of which is the elimination of coal. Similarly, Yancoal, in its 64-page ESG report, claims to be ‘demonstrating its commitment to renewable energy opportunities’ and support for the Paris Agreement.

New Hope, however simply says, ‘Achievable emissions abatement opportunities with positive value will be the first to be considered for implementation’.

Net Zero CO2 emissions is the clarion call but its costs are colossal. BloombergNEF, in promoting ‘investment opportunities’, estimates that to achieve Net Zero by 2050 Australia will need to spend $413 billion on renewables and their back-up, plus $300 billion on transmission. The existing coal-based supply would cost only $80 billion on plant plus maybe $30 billion on transmission!

Even adding in the coal input and operating costs means the system from which we are being transitioned provides energy with far greater reliability at one-third of the cost of the wind /solar system that our political elites favour.

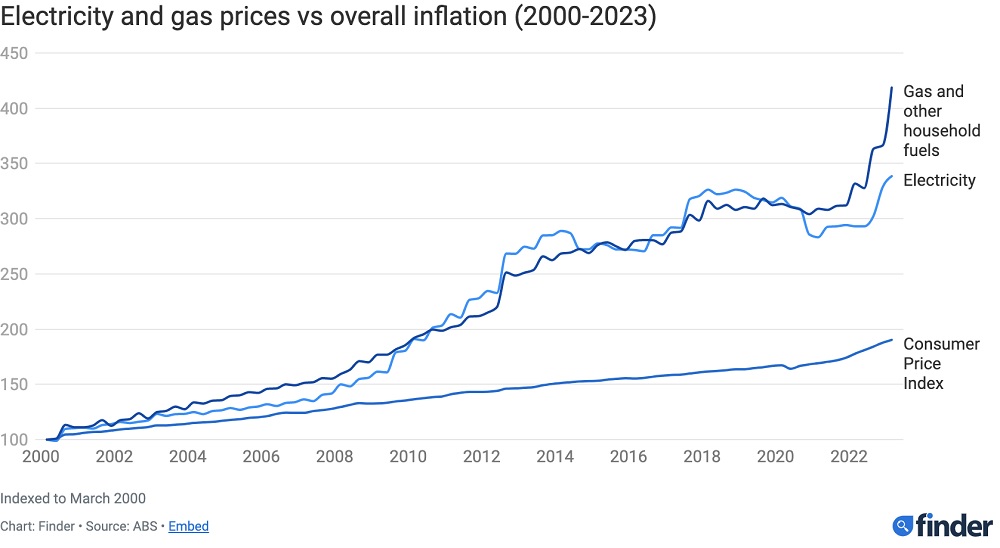

Government regulations on mining and environment have brought electricity and gas price increases at double that of general inflation. This is notwithstanding Australia having the world’s lowest cost coal and gas resources. And the upward electricity price trajectory continues with a further increase of over 20 per cent in place for next month.

Widespread support for manipulating markets to achieve this dismal picture is testament to Charles Mackay’s recognition, nearly 300 years ago, that popular delusions sometimes replace human rationality. But the higher the delusions fly, the harder they fall.