The National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) is set to trial an on-demand platform for the first time during NAIDOC Week with a curated program of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content.

The NSFA Player forms part of its strategy to make the national audio-visual collection more accessible across the country, with content to be both free and pay-per-view.

The Buwindja Collection (‘Remember’ in Dharawal) is curated by Wodi Wodi woman and NFSA senior manager, Indigenous connections, Gillian Moody. Available from June 28, it will comprises 17 titles across feature films, documentaries, TV series and animation, reflecting this year’s NAIDOC Week theme, For Our Elders.

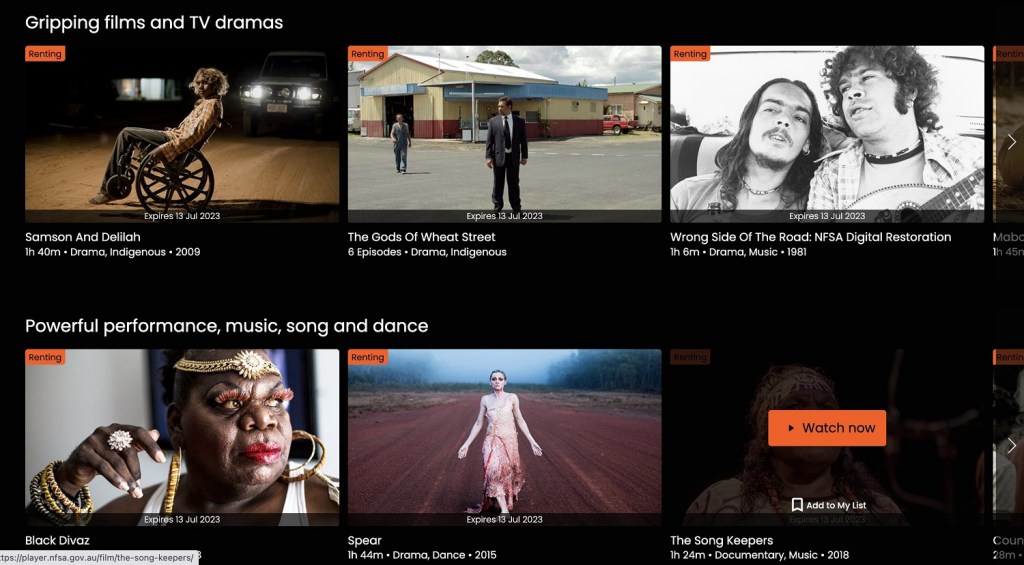

Among the titles are Warwick Thornton Samson & Delilah, Rachel Perkins’ Mabo, Stephen Page’s Spear, Essie Coffey documentary My Survival as an Aboriginal, drama series The Gods of Wheat Street, Ned Lander’s rock n’ roll documentary Wrong Side of the Road, restored by the NFSA, and biographical features about leaders such as Noel Tovey and Ruby Langford Ginibi.

As a filmmaker herself, Moody tells IF the Buwindja Collection is designed to provide a historical arc of how First Nations voices have been represented across Australia screens over time, including highlighting trailblazers who have forged a path. Each piece of content will be presented with a short pre-roll from Moody explaining why she included it, and the context around the production.

“I really wanted to highlight the the sense for many years early on, most of our stories were being told by non-Indigenous filmmakers. They were often socially conscious people and wanted to put those get those stories out to screens to audiences. Then there was a period where that shifted, and there was more of a collaboration; where suddenly more meaningful relationships were happening in the productions of those films and suddenly our Indigenous voices were being credited in roles,” she says.

“Then there was a real shift through the late ’90s into the 2000s, where there were a lot of initiatives being run through places like the Australian Film Commission, SBS and ABC, coming together with state agencies, to create initiatives that were an opportunity for Indigenous filmmakers… to be the authorities of their stories. So there was a real shift from that moment onwards to our films then being made by us. And when I say ‘by us’, in those roles as producers, writers, directors, and seeing more of our people’s faces on screen.”

NFSA CEO Patrick McIntyre tells IF that many other audio-visual archives around the world have streaming platforms of some kind, and it has long been looking for a way to make that happen in Australia. However, given the depths of the NFSA’s collection, just how to launch one appropriately has been a key question.

“Is it a bottomless pit of titles that you search through, or does it remain curated collections over a period of time? These are the questions that we will be asking ourselves,” he says.

NAIDOC Week provided a key opportunity to pilot an approach, given its national significance.

“We’re now thinking further ahead and thinking, ‘What are the what are the kind of significant national or international moments that the institution could help engage people with?’” he says.

“Rather than a carousel of everything in the collection, maybe our role at this point in time is to use the collection to mark national moments or to go deeper on on national themes.”

Moody is excited that the NFSA is testing its on-demand offering with First Nations voices first, introducing people to a just a small sample of what’s in the collection. If the on-demand platform continues, she can see great potential for further First Nations-themed curations, including focusing in on individual directors, actors or production companies.

“It could also be looking even deeper into the archives to the very early productions and films that were made about Aboriginal people and maybe reimagining those, to see what they might look like in today; if we were to relook at those films and put a contemporary perspective onto them. It could be really exciting going forward.”

McIntyre notes that some of the Buwindja collection, and other content that would be available on any NFSA player into the future, may be available elsewhere, including SVODs and platforms like YouTube. However, what the NFSA can provide is a sense of curation and context.

“Where we see that we can add value as the National Film and Sound Archive is to surface [content] in curated pods and draw attention to them. A lot of the material in the collection may have had public investment in. They may have had a cinema release three years ago, but things just disappear so quickly. So they might theoretically be available on another streaming platform, but ten menu levels down. What we think we can do is shine a light on titles that are archival, meaning 1950s, but also archival meaning 2020.”

McIntyre also flags that as the NFSA digitises its collection, digital tools, including AI, are making it much easier to search. That means the collection will ultimately be much faster and easier to curate, and inevitably much more accessible to the public. That means one day, you may be able to find through the NFSA not only episodes or clips from a TV show, but equally an ad from your childhood, or three minutes of footage of your hometown in 1943.

“Institutions around the world that are a couple of steps further ahead than us down the AI route are saying, ‘Wow, we’re finding stuff we didn’t even know we had, that we’ve forgotten we’d had or that we thought were lost’. So all this additional value is being discovered out of existing collections,” he says.

“We’ve got so much of this content that people around the country would love to be able to play with and experience… I can imagine that as we move more towards developing and providing these sorts of tools, you could go into an NFSA-hole like you can go into a YouTube-hole or Google-hole now where you start off with the Aeroplane Jelly ad and end up with a 1930 Australian feature.”

As for First Nations holdings, McIntyre says Australia, like many other countries, has more work to do in repatriating archival content to communities. The NFSA recently built a new studio at the Strehlow Research Centre within the Museum of Central Australia in Alice Springs in order to provide Traditional Owners of Central Australian communities with digital access to the film and audio recordings contained in the unique Strehlow collection.

“There’s just so much work to do to understand First Nations holdings because in past generations they might have been described as ‘Aboriginal’ and it’s like, ‘Well, great, what country, what language, what’s the provenance?’ Institutions around the world are really grappling with this now. And again, I think the increasing digitisation of the collection will enable us to understand it better, and to catalogue and identify bodies of material within the collection that will be super useful and critical to communities around the country who are revitalising language and culture,” McIntyre says.

The new studio in Alice Springs has already had a positive impact on the community, Moody says.

“They’ve actually had some really wonderful moments since having access to that on Country. They’ve learnt that some of the songs that they’ve been singing, for example, they’ve had some of the verses around the wrong way, and so they’ve been able to right that.”