Wildlife director cameraman Mike Herd has written his life story featuring his experiences filming wildlife documentaries throughout the world and the journey that led to the making of the award-winning film ‘Swamp Tigers’. Mike Herd is currently looking for a Bangladeshi publisher to publish his story. This is the second of five chapters from his book, which we are publishing through an exclusive arrangement with the author

17a Belmont street Aberdeen. Photo: Courtesy

“>

17a Belmont street Aberdeen. Photo: Courtesy

“Ok Mike I have a long list of opportunities available but first let me ask you, what would you like to do with your life when you leave school?”

I was almost sixteen, and in the mid nineteen-sixties, that’s when most pupils in Scotland left school. The youth employment officer looked up from his papers waiting for a response. I had only just been told he was in the building and I was caught off guard.

“I don’t know,” I said shaking my head. “I’m interested in chemistry…”

“…Yes…well you would have to go through university,” he said scratching his head.

I didn’t know anybody who had.

“There are lots of trades that are looking for apprentices, you know car mechanics, plumbers, joiners, plasterers, painting and decorating. Are you interested in any of these?”

“No not really, I hadn’t actually thought about work.”

He looked puzzled and rightly so. I suddenly realised it was a strange situation for me to be in. With only a few days to go, I was not only clueless about my future, I wasn’t even in the slightest bit concerned about it.

“Well,” he sighed, “are you any good at sports, you know, football, golf, tennis?”

I smiled.

“No.”

He sighed again.

“What about interests, hobbies, tell me what you like doing.”

He wasn’t giving up.

“I was given a Box Brownie for my birthday and I quite like taking photographs with it.”

His eyes lit up.

“Just a minute,” he said looking through his papers. “Yes here we are, there’s someone looking for a trainee photographer and that would involve mixing chemicals as well.”

It was as simple as that. Had I not been given that camera from my father, my life would have been completely different. Some people believe in destiny and that the future is written in the stars and we merely act out what’s preordained but for me, it was just luck. Either way my very first application for my very first job as a trainee press photographer was accepted and I was paid £1 a week for a period of six months training, then it became permanent, with a proper wage. That was the year when Nelson Mandela began twenty-seven years imprisonment, President Johnson signed the American Civil Rights Act abolishing racial segregation and the Beatles and the Rolling stones burst onto the music scene.

Scotpix, the freelance news agency owned by Geddes Wood, had its offices in a Victorian ramshackle of a building on two floors above Findlay & Company’s shop in Belmont Street, Aberdeen. Up in the attic floor was a darkroom next to a small office rented to Ron Lyon a reporter for the newly published Sun newspaper before the broadsheet was bought by Rupert Murdoch. I was in the downstairs office scouring the Press and Journal for ideas that might lead to a story. Previously, I had come across a petrol station with guard geese that cackled and hissed at anybody coming near the pumps. It made a nice picture feature. I scanned the lost and found column which can occasionally throw up the odd story. A little girl with a missing kitten tugging at the heart strings, that sort of thing, but there was nothing. It was the silly season when news was in short supply and sometimes small columns in the papers were just made up to fill the space. The P&J regularly carried stories about a famous Italian opera singer that nobody had ever heard of who was frequently getting herself into unfortunate scrapes.

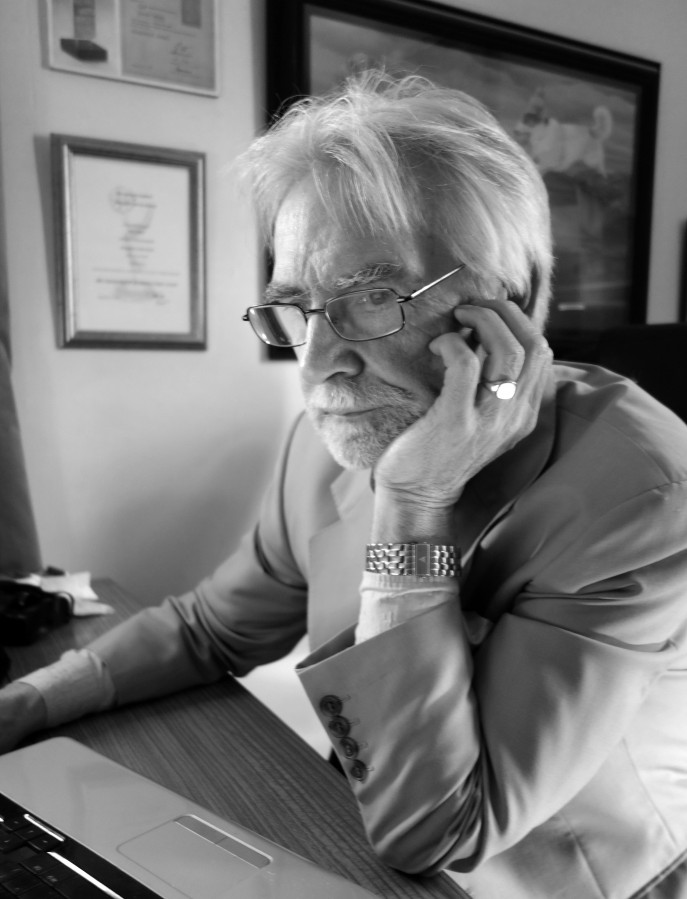

Mike Herd writing. Photo: Courtesy

“>

Mike Herd writing. Photo: Courtesy

I put the paper down and sniffed. There was a smell of smoke. I turned round and looked across the room. Seeping from behind a blocked off fireplace was a steady stream of smoke. Years of soot had caught fire and the smoke was getting thicker. I called the fire brigade forgetting Ron was upstairs and as the fire engines with sirens blaring approached, he phoned them to find out where the fire was. He came charging downstairs in alarm to see what was going on.

The silly season ended early with a bang as a major international story broke. I steadied my twin lens reflex Yashica Mat camera on the edge of a parapet high above Union Street. Below, lit only by street lamps was an extraordinary scene. Over a hundred thousand people, almost the entire population of Aberdeen stood still, silently waiting and then she appeared from the Town House balcony and the crowd went wild.

The Queen had come to give Aberdeen the all clear after the worst outbreak of typhoid seen in Britain since 1939. The wall of noise that rose and hit me was incredible. She smiled and waved, then gave a speech, of which I cannot remember a single word but I’ll never forget the taste of euphoria from the people of Aberdeen and an outpouring of emotion that signalled an end to the nightmare.

The year I began work coincided with the biggest story ever to hit the city. It all started from a large Infected tin of corn beef. Daily, the increasing numbers of people falling ill with typhoid were splashed across the front pages. At the height of the epidemic over five hundred people would be quarantined. Haunting images of whole families inside Woodend Hospital looking out from ward windows holding cards with messages on them to relatives and friends standing outside. Some bewildered children quarantined on their own would stand at the window, touching the glass with the palms of their hands while mums did the same from outside.

Regular meeting places where large numbers would normally come together were closed. Cinemas, dance halls, football matches were put on hold and schools were closed. Panic in the national media reported bizarre scare stories of people dying in the streets in fact there were only three deaths, all elderly. Some tourist agencies would not accept hotel bookings from Aberdonians unless they had a vaccination certificate. People who had to travel south claimed they were from small villages far from Aberdeen. At the height of the infection and over only one twenty-four hour period, thirty-nine patients were admitted to hospital.

By the very nature of the job, I had no idea what I was going to do from one day or even one minute to the next and I loved that. It would always start with the phone ringing. Circulation wars flared up between the nationals. Every story no matter how trivial was covered. Journalists in taxis would follow rival newspaper men to find out where the story was, it was fun. The Daily Express two doors down had a large glass window and saw all the comings and goings. Saturday was the busiest and craziest day.

I covered many weddings for the Sunday’s running from one church to another, getting names and addresses then racing back to the office, developing the film and printing off sets of photographs of the couples outside the church. I literally had to run with the marked envelopes down Belmont Street, across Union Street, down a long flight of stairs to the Green that led to the railway station. There were times when the 5.45pm train south was moving out of the station platform and I had to run after it holding out the packages to the outstretched hand of the guard. On a couple of occasions when I missed the train, Geddes would have to race through to Stonehaven in his car to catch up with it. Then there was football.

“You’ll have to take over the football,” said Geddes, wincing as he touched his bruised head.

He had been covering an Aberdeen match at Pittodrie when a fan threw a bottle hitting him on the head. When Geddes threatened to sue Aberdeen Football Club they promptly banned him. I wasn’t in the slightest bit interested in the sport.

“I don’t know anything about football,” I protested. “I don’t even know who the players are.”

“You’ll learn. Just make sure you get the team sheet and sit behind one of the goals. Watch what the other photogs do.”

Somehow it worked, I still don’t know how. I was getting better pictures than the others. Maybe it was because they were anticipating what was going to happen too early and with those manual wind on cameras, you only got one chance at any goal attempt. Geddes wrote most of the captions and I seem to remember ‘goalmouth stramash’ being used rather a lot.

P&J photographers still used Speed Graphic, five by four inch glass plate cameras, the kind you would see in thirties American gangster movies. You always knew they were photographers even when they were off duty. One shoulder would be lower than the other because of the weight of the camera and the glass slides. While we were all rattling through the shots one Journals photog would take only one photograph and it would inevitably be the best.

Working as a photographer was scary and exhilarating and I made mistakes, plenty of them. I had to learn everything from scratch but the key thing was learning from them, not repeating them. Every conceivable event was covered. From murder trials and shipwrecks, blizzards in the winter or royal visits, we covered them all.

A new Bishop was ordained in Aberdeen, the only problem was that since I had never seen a Bishop before, I had no idea what one looked like. There were so many people in ceremonial dress, that I didn’t have a clue what I should be looking for and missed them in the procession. That did not go down well.

The Scotpix office was an all inclusive open house. People would come and go. Some were introduced to me, some not. Sometimes attractive models would hang out, I never understood why. Photographers of all shades and sizes came and went but I stayed. He gave them a chance to work under whatever business arrangements they had agreed to. I had to leave my family Doric language behind when I worked. When questioning why it wasn’t spoken in schools I was told it was slang. One photographer who bravely spoke broad Doric, bless him, was described by Geddes as a rough diamond. Unfortunately he swore quite a lot which I wasn’t used to hearing.

Geddes was a kind and generous man who welcomed everyone in a liberal, Bohemian way. They kept on coming and they kept on going. A couple of reporters did work out of the office but only because they couldn’t hold down staff jobs with alcohol playing a big part in that. Journalists had contacts of course but the main source of stories came from the pub. That was when people were more relaxed and confiding so drink was part of the risk journalists had to cope with.

One reporter liked to cover the courts. I would sit through trials so that I could identify those involved in interesting stories and photograph them when they left court. They were mostly a string of pathetic people who should have been cared for instead of being fined or sent to prison.

I saw an ad in a magazine that intrigued me.

‘Ship’s photographer wanted for the Reina del Mar.’

“I was wondering what it would be like as a ship’s photographer,” I asked Geddes.

“I don’t mind, try it out and see what you think of it. If it doesn’t work out, come back, the job’s open for you,” he said.

So I found myself on a train heading south and on crossing into England I was hit with a serious bout of homesickness that tied knots in my stomach.

On board, I shared a cabin with another new recruit and once I got started, very quickly realised it was not for me. The holiday cruise ship sailed from Portsmouth into the turbulent Bay of Biscay and with an almost permanently lingering feeling of sea sickness, was told to change the film cartridges in the dark room.

Not only did I have to concentrate on what I was doing, I was also fighting the unpredictable roll of the ship in complete darkness. The only food I could keep down were salads. One day I made the mistake of using salad cream and ever since then, its taste makes me queasy. She spent a day docked in Senegal in West Africa then returned via Madeira. I was walking through an old square in the town when I saw a film crew and thought to myself, that’s what I should be doing. I’m sure I wasn’t the best ship’s photographer ever but I didn’t care. I was just glad to go home after my ten day trip.

“This is Ray Bellisario,” said Geddes. “He needs an assistant for the day.”

It was as if I hadn’t left, the ship episode was a faint memory. We shook hands then sped off along North Deeside Road heading West to Braemar in his hired car. It was autumn, nearing the end of the highland games season and the highlight was the Braemar Games. On the way he explained that he was a photographer from London and the very first paparazzo before the term was coined. He would stalk the royals wherever they were.

The Balmoral estate was a happy hunting ground at a time when there was a lot going on especially with the maverick Princess Margaret. Even in those early days he was persona non grata by the royal family and wore it as a badge of honour.

Being not accredited of course, we had to find a position in the rolling landscape from a safe distance yet close enough to get some pics. He didn’t use a tripod not wishing to attract attention so I sat with my legs stretched out and he placed a barrel of a mirror lens on them for support. Ray had spent most of his life photographing people who did not want off-guarded snaps taken of them. The UK press wouldn’t touch his photographs so he sold them to Paris Match and Der Stern.

Apparently happy at the photographs he took, we returned with the skirl of the pipes seemingly following us all the way back to Aberdeen. In 2013 he would sell all of his photographic archive at auction for charity. I had been four years with Scotpix and felt that it was time to move on.