A year after Jalen Randle was fatally shot by a police officer, Tiffany Rachal still has many questions about the circumstances leading to her son’s death. Among them, she wonders, would he still be alive if he weren’t Black?

Black residents make up 22 percent of Houston’s population, but they account for 72 percent of people who suffered serious bodily injuries at the hands of police and 63 percent of people who died as a result of police use of force since the beginning of 2020, according to data from the Houston Police Department’s transparency hub, a publicly available online database.

About 55 percent of the department’s 28,945 reported incidents involving a use of force were committed against Black residents.

MORE ON RANDLE: What to know about Jalen Randle and the Houston cop who could eventually be indicted in his death

“For us to be targeted 72 percent of the time shows the major biases and racism that we’ve been trying to get away from since slavery supposedly has ended,” said RoShawn Evans, the organizing director of Houston-based Pure Justice, a nonprofit organization aimed at reforming institutions that perpetuate injustices.

The statistics stand in stark contrast to the department’s diversity statistics — the percentage of employees that identify under each racial category.

About 24 percent of the department’s 6,147 employees are Black, surpassing the citywide percentage by 2 percent; about 35 percent are white, exceeding the 23 percent of the city population; 31 percent Hispanic or Latino, compared with 46 percent citywide; and 8 percent are Asian, surpassing 6 percent citywide, according to department data.

The officers who have inflicted serious bodily injury on the job are more likely to be white. Among the 281 incidents in the database, about 49 percent involved injuries inflicted by white officers, compared with about 2 percent involving Black officers, according to the data.

Advocates and survivors say the race of police officers should be a consideration in investigations.

Rachal, whose son was killed in Houston April 2022, questioned why the Memphis Police Department was so quick to act and investigate the Black officers accused in the death of Tyre Nichols, but she said police haven’t been as quick in cases when the officers are white.

“Why is it always, when it comes down to white men, you have to wait for the video to determine whether something is wrong or right?” she asked.

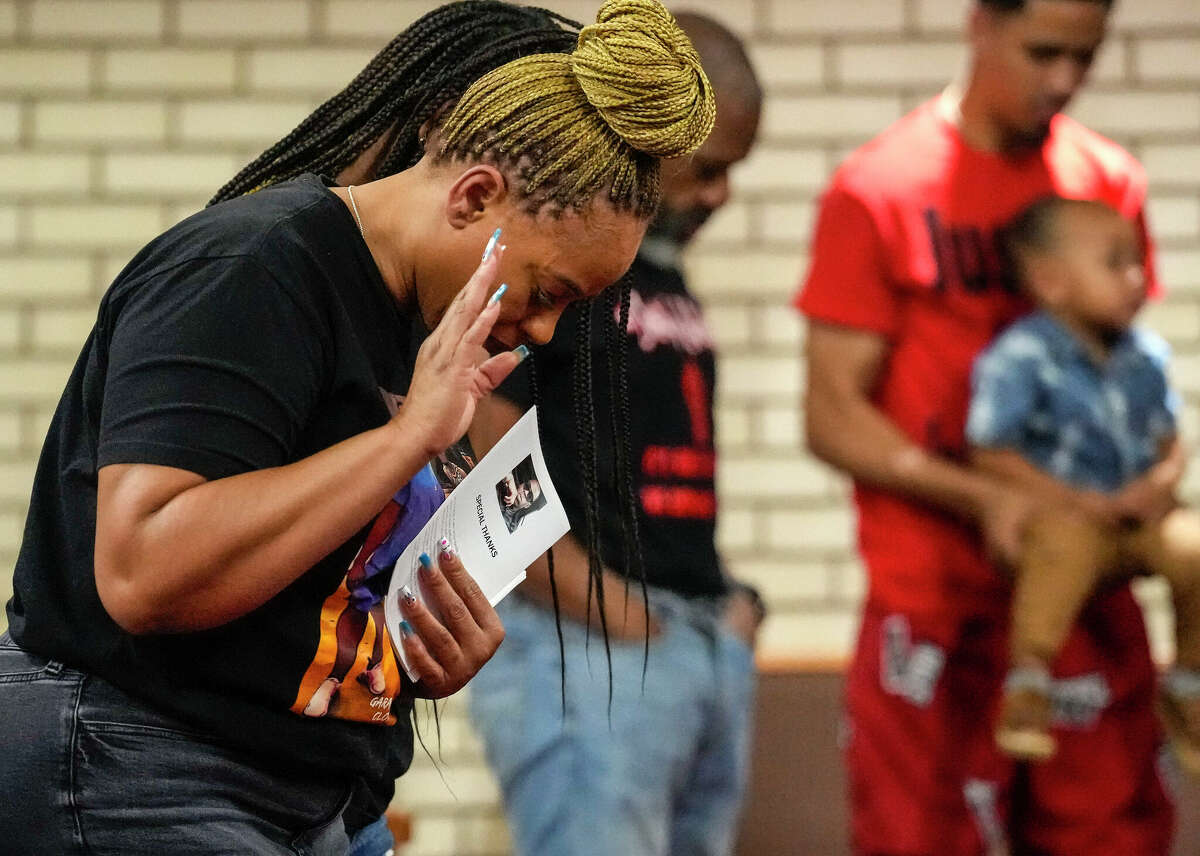

Tiffany Rachal prays during a memorial service her son, Jalen Randle at Fifth Ward Missionary Baptist Church on Friday, April 21, 2023 in Houston. Jalen Randle was was fatally shot by an HPD officer nearly a year ago.

Karen Warren/Staff photographerAbout 54 percent of all 7,062 use of force incidents since 2022 were committed against Black residents, according to the data.

In response to questions about the city’s use of force data, police officials said discrimination in any form, including racial profiling, is prohibited and the department would take immediate action to investigate any allegations. Anyone who believes they have been subjected to use of force because of racial or other profiling should submit a complaint, police said in a statement.

Evans, from Pure Justice, criticized that approach, explaining that the process of submitting a complaint is intimidating because it often requires visiting police departments and residents often don’t trust police to investigate themselves.

But both academic and law enforcement experts, along with some community activists, said the reality of police interactions with Black residents and minority communities is complicated and it can’t simply be solved by improving staff diversity or offering better training. Rather, these interactions are influenced by systemic and societal factors, such as the intersection between race and class and the fundamentals of preparing officers to carry out their duties.

NICHOLS REACTION: Houston leaders, community protest to Tyre Nichols police beating video

“You have unprotected communities with no power and you have police going in with a whole different approach based upon their experience and understanding – it’s a recipe for dehumanizing people and causing further harm,” said Vanesia Johnson, a local activist who works in community mental health.

Evans said many Black people are victimized due to systemic problems that have placed many Black residents in generational poverty. Addressing these problem calls for solutions beyond the realm of law enforcement, she said.

High crime amid high poverty

Law enforcement professionals have taken initial steps in recent years to address these systemic issues, such as by working to increase diversity within the police department’s ranks and instituting new training to teach officers about what they might encounter.

Increased diversity in the Houston Police Department is a good thing, said Douglas Griffith, president of the Houston Police Department. Each of the five experts interviewed for this story agreed. It will give administrators better perspective into the communities they serve, along with a host of other benefits, they said.

But modern circumstances mean police are being asked to solve societal problems, best addressed by other entities, Griffith said. The department statistics reflect the fact that officers are frequently assigned to patrol in high crime areas, which typically coincide with places with high poverty rates, he said.

The poverty rate for Black Americans was around 19.5 percent in 2020, compared with 8.2 percent for non-Hispanic white Americans, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Howard Henderson, a professor at Texas Southern University, agreed with much of Griffith’s explanation, and said he thinks use of force outcomes would change if elected leaders focused on issues beyond policing, including better social services, mental healthcare and access to a safety net.

Johnson, the mental health advocate and community activist, said police are in an impossible position where they’re expected to make unilateral decisions about when and how force is used in communities they work in.

“If an area of town is declared Public Enemy No. 1, that you have a higher likelihood of losing your life, then you’re going to go into that area differently,” she said. “That’s true if you’re an officer or a visitor from out of town. You see it as a community threat, you don’t see the individual people.”

No indictment for officer who killed Randle

Rachal agreed with Johnson that many officers don’t people as people. She recalled going to the hospital after learning her son had been shot and said no one from the police department would talk to her. Many of the officers were Black, she said, but it didn’t seem to matter to them that she was grieving.

In April, Randle’s family members learned a Harris County grand jury did not plan to indict Shane Privette in the fatal shooting of the 29-year-old Black man. The decision means they the family must wait longer to find out whether the officer will face criminal charges.

Privette had been indicted once before on allegations he brutally assaulted a man during an undercover drug bust in 2017. Those charges were dropped two years later after a second grand jury reviewed new, unspecified evidence.

Mother Tiffany Rachal, 51 of Jalen Randle, who was fatally shot by Houston police officer Shane Privette in April 2022, prays alongside family and friends as they wait for a decision from the Harris County grand jury on Wednesday, April 26, 2023 in Houston. The Harris County grand jury decided to take no action on potential charges against Houston police officer Shane Privette, meaning the case will be presented to a new grand jury as soon as is practical.

Raquel Natalicchio/Staff photographerThe earlier indictment has been a point of contention for Rachal and her friends and family members. They don’t understand how Privette and officers like him can slip through the cracks.

Part of the deeper problem may be the need for police officers to process their own emotions about the situations they encounter on the job.

CASE EXPLAINER: What to know about Jalen Randle and the Houston cop who could eventually be indicted in his death

In Johnson’s work as a mental health professional, she has talked with officers who’ve mentioned the stigma attached to seeking mental health counseling. That trauma many have accumulated is an underrated factor in their interactions with the public, Johnson said.

“We’ve seen what happens when you don’t take care of soldiers’ mental health,” Johnson said. “And they’ve gotten better about sending them early to get counseling for the things they see.”

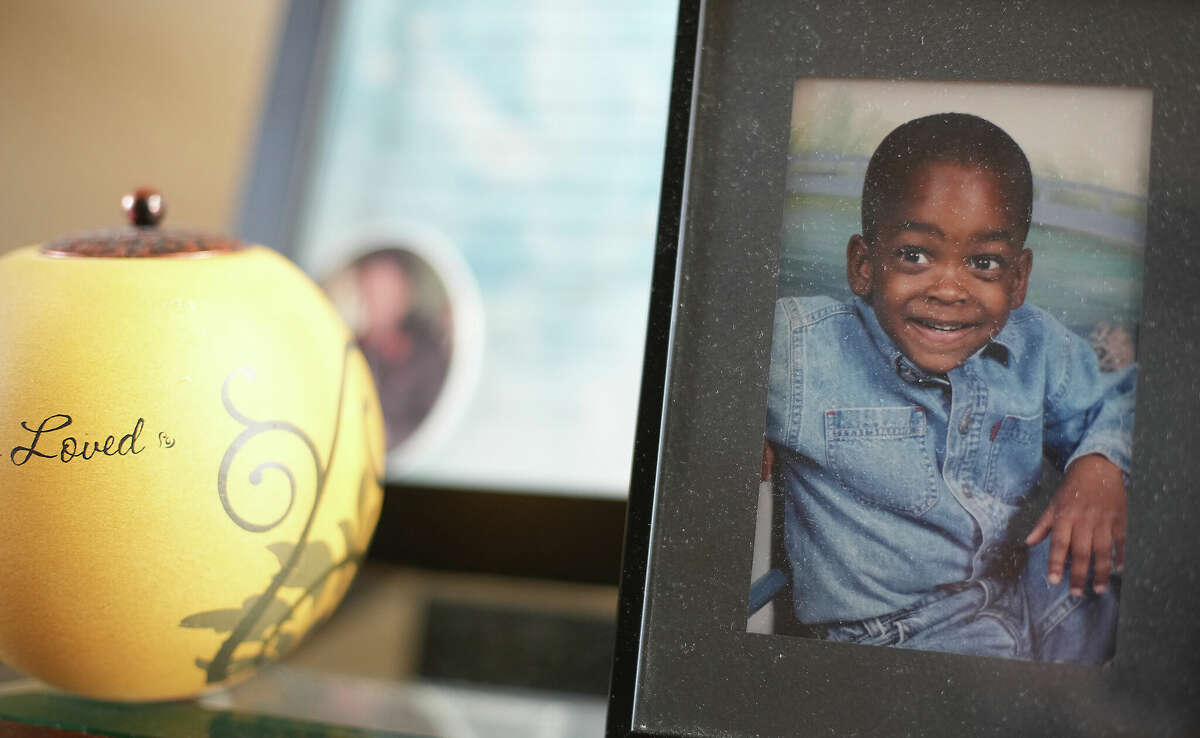

A photo of Jalen Randle when he was two years old sits in the entry way of his mother, Tiffany Rachal’s home on Monday, April 3, 2023 in Cypress. Randle was fatally shot by a Houston Police Officer last year after a chase.

Elizabeth Conley/Staff photographer