New technology and ground-breaking science are unravelling ancient secrets and bringing characters from the past back to life.

Sometime in the cold winter of 1235, the formidable figure of Bishop Walter laid his head down and took his final breath.

Raised in Galloway, he had spent time in York before returning home to the sanctuary of Whithorn where, in 400AD, St Ninian built his ‘Candida Casa’ – shining white church – and brought Christianity to the Picts.

Within the cool stone walls of the 12th-century priory, Bishop Walter, his once red hair long since turned to grey and fully dressed in his finery, was laid to rest accompanied by a wooden crozier and a glittering ruby and emerald ring.

That may have been the end of Bishop Walter. However, 21st-century technology and remarkable science have now combined in a manner that would surely have blown his medieval mind.

Having departed this world in the early 13th century, the Bishop – along with others laid to rest in the Christian cradle of Whithorn centuries ago – is set to rise again.

Forensic work on his and the skeleton remains of three others excavated at the priory site in the 1980s has already revealed fascinating images of how they almost certainly looked.

READ MORE: Abandoned 100 years ago, this Shetland island remains in hearts of descendants

Bishop Walter’s image was reconstructed using modern technology (Image: University of Bradford/Chris Ryan)

Now those images are being merged with a raft of new research carried out into the landscape, buildings, clothes and even the food they dined on and the illnesses they struggled with, to create an immersive virtual reality world that transports users back in time.

The first element, a new app, will be unveiled within weeks. Combining the latest digital technology with archaeological and scientific discoveries, ancient documents and expert knowledge, it will enable visitors to Whithorn to flip between three eras – early Christian, Scandinavian-Viking and medieval using their smartphones, visiting reconstructed sites brought to life.

Developed by the School of Computer Science at St Andrews University, the app will eventually be joined by a game-style virtual reality experience.

Designed to be used with Oculus headsets, it will give wearers the chance to wander in the footsteps of Whithorn’s ancient dwellers, explore churches, examine relics and fly through villages.

Among the most intriguing elements will be the chance to come face to face with the rotund Bishop Walter and other characters whose features have been recreated by craniofacial anthropologist and forensic artist Dr Christopher Rynn from the University of Bradford.

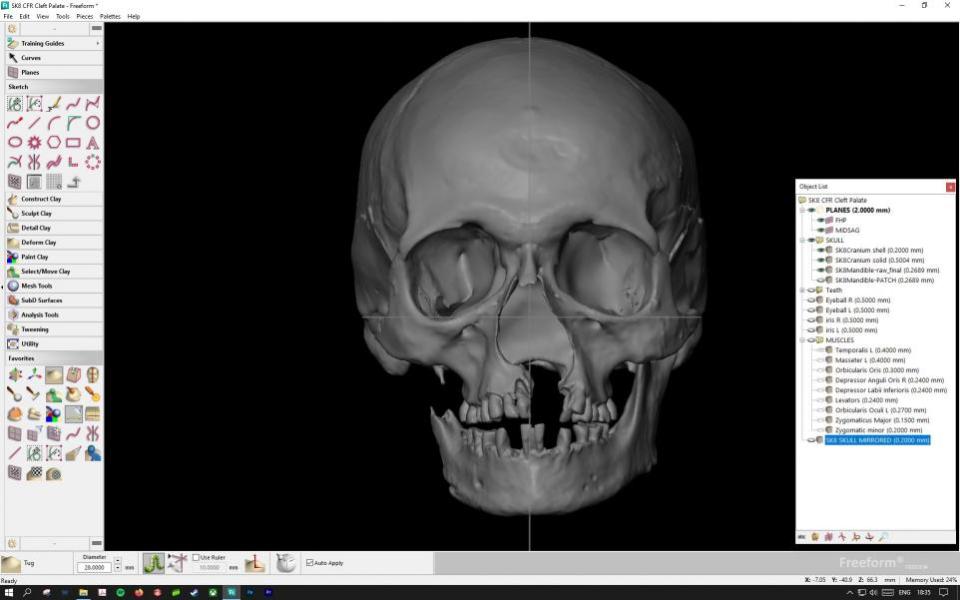

Detailed reconstructions of Bishop Walter, his counterpart, the dark-haired and dark-skinned Bishop Henry, a mystery cleric with a distinctive cleft lip and a beautiful young woman were made using three-dimensional scans of each skull.

Their virtual reality rebirth in the new app is just one element of a multi-layered project, Cold Case Whithorn, which has brought universities, academics, archaeologists and historians dotted around the country together. Using the latest science and technology, they are gradually peeling back the centuries to reveal fine details of the life, times and experiences of the people who may have lived but certainly died at Whithorn.

Excavations carried out in the 1950s and later at the site, which has drawn pilgrims, traders and Christians for centuries, saw hundreds of remains discovered and removed. They included the excavation of graves of highly esteemed clergy, laid before the high altar.

While for decades researchers were limited in how much information they could glean from skeletons and objects left in their graves, from buckles to brooches to rare altar vessels and insignia of clerical office, new technologies mean they can delve much further and reveal previously unimaginable details.

READ MORE: How the 1953 coronation was marked in Scotland

One of ‘Cold Case Whithorn project’s latest elements has seen ancient DNA analysis carried out on Bishop Walter and a further 30 skeleton remains by the Crick Institute, a biomedical research institute in London. Using new genetic sequencing technology, it has revealed his hair colour – red – and the colour of his eyes, blue.

The DNA results will form part of a major Cambridge University project into changing human health.

While scientists led by Dr Shirley Curtis Summers of Bradford University have used stable isotope analysis, which studies the chemicals absorbed into bones and teeth, to reveal the secrets of diet and climate, even pinpointing where someone grew up – drinks absorbed during childhood leave a marker which the technology can identify.

At the same time, inorganic materials such as glass, plaster and metalwork excavated from Whithorn has been analysed, throwing forward intriguing results that link glass fragments with Palestine and the Roman era.

Julia Muir Watt of the Whithorn Trust, said: “We are building up a detailed picture of mediaeval people and the places they lived in based on advanced scientific analysis, which now allows us to pin down detail and then envisage them and their environment through digital means in ways that we couldn’t have dreamt of previously,” she said.

“It just seems that the past is getting closer.”

A key element of the latest work has been the digital recording by Napier University students of thousands of artefacts gathered during 1980s and 1990s excavations onto an online database to make future research possible.

But it is the human remains, which stretch from the 6th to 15th centuries, which hold the most promise.

“This was an ecclesiastical site, there was a community that was important and the human remains collections is huge,” Julia added.

“The human remains can tell us of population changes and even when the monastery came into existence: the male burials appear in nice, organised rows.”

Other analysis has confirmed that local people were often buried alongside people who had arrived from elsewhere, helping to debunk notions that they were conquered by incomers.

“We can draw some big cultural conclusions; that locals were not cowering, conquered, depressed and subservient to newcomers, they were doing rather well.

“And we can also see newcomers adopted old ways – there was clearly cooperation.

“The science is amazing,” she added.

Analysis of some of Scotland’s earliest stained glass had also shown surprising details that suggest it had been recycled and reused.

“University College London carried out amazing chemical analysis that tells us where the glass was made – from Palestine and parts of the Roman Empire. So, they were recycling glass from different sources.

“We also found very rare glass only found in Egypt and Jarrow. It gives us this amazing picture of the exchange of personnel and technology between the great monasteries within the north kingdom.”

The new discoveries will be incorporated within the new orientation aware app, which enable users to point their phone at certain locations to see what would have been there across the three eras.

Dr Alan Miller of University of St Andrew’s School of Computer Science said the app draws on expert knowledge from a range of sources to ensure it is authentic.

“Clearly any reconstruction is going to have some conjecture involved in it, but what it is state of the art in terms of our understanding of the site,” he added.

“The app is a visualisation of lifetimes of study and investigation, so users can appreciate the archaeology and this knowledge and understanding is much more accessible.”

“The characters appear in a landscape and settings that are in a lots of ways not really changed that much.

“It helps people really understand or imagine what the past was like – it makes it much more real and not just words on a page.

READ MORE: Marchmont House owner Hugo Burge dies aged 51

Julia said wrapping the reconstructed faces of real-life people such as Bishop Walter onto moving characters brings it even more to life.

“When we imagine a medieval cathedral, there’s a tendency to think it was very drab but in reality it would be full of over-the-top colours, lights, smells, and be highly decorated.

“It’s the same with the people. We study them, store them in boxes, send their samples away. But when a specialist comes up with a face, and it turns to look at you… it can be quite eerie.

“You have to wonder what Bishop Walter would have made of his resurrection.”