- Dee Bradshaw

- A Pride Parade float for the Sacred Light of Christ Church.

Editor’s Note: The following article was published as part of City Weekly’s 2023 Pride Issue.

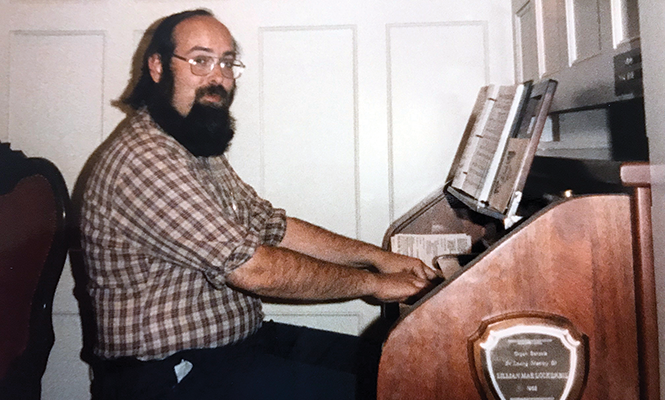

Within the walls of a modest 1913 structure just north of Liberty Park on 600 East, Berry Payne prepares the chapel of Sacred Light of Christ Church. As music director, Payne is dutifully carrying out responsibilities that he has held for 13 years.

“This has been my home for a long time,” he says. “They’re another extension of my family.”

Acknowledging that he was gay when he was 12, the church has been a “sanctuary” for Payne—on and off—since he first became acquainted with it in the 1970s. Back then, it was known as the Metropolitan Community Church, a nondenominational Christian organization famous across the country for its pro-LGBTQ+ message.

Payne discounts the notion that “one church is better than the other.” For him, it’s where one feels most “at home” that matters. Besides, he said, “most churches are accepting now.”

Indeed, the road to increased acceptance has been as hard-fought and painful as it has been joyous and exhilarating. This Pride Month, City Weekly looks back on the story of Salt Lake’s Metropolitan Community Church and the part it played as Utah’s LGBTQ+ community developed.

Lavender Scare

Prior to the mid-20th century, there were few community centers for gay and lesbian Salt Lakers to feel connected and nourished as their fullest selves. Cruising—or at least furtive gazing—was pursued by some, and locations like Liberty Park (900 S. 600 East, SLC) and what was Wasatch Springs Plunge (840 N. 300 West, SLC), and Deseret Gymnasium (formerly at 161 N. Main, SLC) provided semi-private venues at which locals and travelers made brief forays.

But it was World War II, wrote Douglas A. Winkler, author of Lavender Sons of Zion: A History of Gay Men in Salt Lake City, 1950-79, that exposed men and women to “unprecedented opportunities for homosexual desire” in the barracks and the factories. American gays and lesbians began developing more defined subcultures in cities across the country, and Salt Lake was no exception. Starting in 1948 with Radio City Lounge (147 S. State, SLC), bars became the unofficial centers for Utah’s dispersed LGBTQ+ community.

“One man’s prison and another’s refuge,” observed Winkler, “Salt Lake never seemed large enough for some, while others appreciated its anonymity.”

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had also changed by the postwar era. A non-erotic culture of same-sex dynamics had been traditional within Mormonism, argued the late Mormon historian, D. Michael Quinn, in a 1996 study—one that could be traced back to 19th-century mores in its approach to what Quinn described as “extensive social interaction, emotional bonding and physical closeness.”

Homosexuality, on the other hand, was rarely broached, and when it was privately addressed, Quinn reports that church officials “responded to homoeroticism in ways that often seem restrained, even tolerant, today.”

This “live and let live” response was described by Earl Kofoed (1923-2000) in an April 1993 issue of the Affinity newsletter. Reminiscing about his days as a gay Brigham Young University student, he recounted a 1948 meeting between two fellow gay classmates and then-Church President George Albert Smith (1870-1951).

After declaring their love for each other, Kofoed wrote, “President Smith treated them with great kindness and told them, in effect, to live the best lives they could. They felt they had gambled and could have been excommunicated right then and there; instead, they went away feeling loved and valued.”

Conditions swiftly changed by the 1950s, however, as the so-called “Lavender Scare” of the Cold War era swept the country in the guise of federal and state purges—enhanced sodomy laws and frequent police raids of popular gay spaces. This was particularly true of then-Salt Lake City Police Chief Cleon Skousen, who, according to Winkler, embodied “both the national security state and an uncompromising, conservative brand of Mormonism. His administration was a harbinger of the LDS Church’s hardening stance toward homosexuality, which reached a fever pitch during the 1960s.”

Under the influence of such figures as J. Reuben Clark, Spencer W. Kimball and then-BYU president Ernest L. Wilkinson, homosexuality was now something that was talked about openly and in the most hostile of terms. To these prominent leaders, homosexuality was not an aspect of a person, but an act requiring eradication by any means necessary, from shock treatment and spying to psychiatric confinement and police entrapment.

But two events at the close of the 1960s heralded dramatic changes to come. The first came by way of a defrocked pastor in Los Angeles, the other from a tavern in New York.

Having been ejected from his Pentecostal ministry in the East, Troy Perry relocated to Los Angeles to start anew as an openly gay man. Outraged by the raids used by local police to target gay clubs—and the devastating effects such practices had upon loved ones—Perry resolved to act with his calling.

“Tremendous need existed for a bold ministry,” Perry later wrote. “Literally tens of thousands of homosexual sons and daughters, sisters and brothers, plus our friends and the friendless in every age group from puberty on, who had been robbed of their self-esteem, were waiting to find and heed our basic message, ‘God loves you!'”

The 1970s ‘Renaissance’

Starting with a small group at Perry’s home in the fall of 1968, the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) began. In four years, his church had grown to 35 congregations across 19 states. In an era before marriage equality, MCC even started performing same-sex weddings—or “Holy Unions”—in 1969.

And while the MCC was spreading around the country, another revolution boiled over at the Stonewall Inn in New York City.

Like countless other gay meeting places, the Greenwich Village bar was a routine police target. But during one early morning raid on June 28, 1969, the patrons at the Stonewall had had enough, erupting into a spontaneous riot against police violence.

By the following year, communities around the nation began marking the occasion with Gay Pride celebrations, and a more assertive form of gay rights advocacy by groups like Gay Liberation Front had come into being.

Ben Williams is a long-standing chronicler of local gay history. Of Utah’s gay community following Stonewall, the retired teacher considers the 1970s a “Renaissance period.”

“I met so many really valiant people here, against all odds when we had no allies,” he said.

It would not be long before an MCC congregation began its ministry in the Beehive State. And according to Williams’ chronology, locals met at a private Bountiful home in the early 1970s to organize an outreach. “All this stuff starts with a few brave people coming out and doing things,” Williams said.

The Salt Lake chapter of MCC began meeting at the Unitarian Church at 569 S. 1300 East, SLC, in 1972. Before long, it relocated to 740 S. 700 East, SLC, under the leadership of Richard L. Groh, who performed Salt Lake’s first Holy Union that November.

A letter from Troy Perry celebrated the chartering of the new church, with the hope that it would become “a real lighthouse in the Rocky Mountain states.”

Already, by early 1973, Utah’s first gay hotline was established through the Salt Lake Community Mental Health Center, whose staff trained five members of the MCC congregation in crisis intervention. In return, as one MCC publication reported, “the mental health personnel underwent a most interesting training session as to crisis intervention in our ‘special community.'”

Relocating again to 870 W. 400 South, SLC, MCC enjoyed its first real opportunity to interact with the larger public, for the building was also used by other local organizations and clubs.

Candace Naisbitt remembers her time as Salt Lake’s MCC pastor as “a gift.” Originally from Ohio, Naisbitt discovered MCC in California’s San Fernando Valley in the early 1970s.

Training for the pastorship and serving in Stockton with Alice Jones (1937-2013), they were MCC’s first team ministry, coming to Salt Lake City to replace Michael E. England after the latter resigned from that all-too-familiar malady: burnout.

Although she and Jones differed in approach, “we worked well together,” Naisbitt recalls.

They served a congregation that has fluctuated in size—anywhere from a small handful to more than 100. Internal dissension led some factions to start anew elsewhere, but Naisbitt recalls a warm and generous group during her stay between 1975-1976.

“Most of the church members lived on a very, very tight thread,” she remembers, and operating the church with few resources was a struggle in her role as clergy. Most of her labors included hospital visits and helping congregants to regain their confidence by erasing the notion that LGBTQ+ people were going to some erroneous concept of hell.

“They were looking for a place to become,” Naisbitt concludes, and the “rich” experience of helping them has instilled in her a spirit of gratitude to this day.

- Dee Bradshaw

- In 1977, Bob Waldrop led groundbreaking protests against Utah’s then-lieutenant governor as well as singer Anita Bryant.

Utah’s Stonewall

By the time Bob Waldrop (1952-2019) arrived to take the reins as MCC’s pastor in 1977, much had changed for gays and lesbians in Salt Lake City. By then, Joe Redburn (1938-2020) and Nikki Boyer had established the state’s first openly gay bar with The Sun Tavern in 1973 and even organized gay celebration events in places like City Creek Canyon.

MCC had been responsible for the state’s first gay-friendly newsletter with The Cricket, but since then, Utah gays and lesbians had established their own newsletters in the mid-1970s, like The Gayzette, The Salt Lick and The Open Door. The Imperial Court—which presented extravagant drag shows to raise money for charity—also began serving the community at this time.

To many in the larger public, gays and lesbians did not yet have a voice to which anyone felt obligated to take heed. In some respects, Waldrop supplied that needed voice at a critical time. Remembered as “a firebrand” by Williams, Waldrop was a key figure in a 1977 protest that scholars came to refer to as “Utah’s Stonewall.”

“[Waldrop] was taking on the government, taking on the state, taking on the [LDS] Church, taking on everybody,” Williams said.

Waldrop’s efforts came to a head when then-Lt. Gov. David S. Monson revoked MCC’s approval to hold a dance in the Capitol, which coincided with a national, anti-gay “Save Our Children” campaign, spearheaded by singer/spokeswoman Anita Bryant. Working with the ACLU to sue Monson, Waldrop became, in the words of University of Utah researcher Charles Perry, “a dynamic spokesman for the gay community, articulating its aspirations and outrage.”

Utilizing the networks afforded them through the local bars, MCC, Imperial Court and other groups, Utah’s gays and lesbians came together to protest the lieutenant governor. And when Bryant was booked to appear at the Utah State Fair, enough was enough.

Waldrop brought leaders of various gay organizations together in the basement of the MCC to coordinate their response and prepare a protest at the fairgrounds, as well as other events like a dance and talent contest by MCC, an Imperial Court kegger, special programs by the Sun Tavern, Radio City Lounge and the lesbian bar Uptown, as well as a candlelight vigil in Memory Grove under the direction of the group Women Aware.

“The Anita Bryant protest provided myriad opportunities to heighten morale, gather resources and foster community,” Charles Perry wrote of the occasion.

The protest invigorated local gays and lesbians and even found some sympathetic observers. However, the general solidarity throughout the gay community would be fragile, as divisions and fatigue took their toll.

Williams reports that Waldrop himself began to burn out, compounded further by the numerous death threats he personally received, the vandalism routinely directed at MCC, and the unsolved murder of his friend, Anthony “Tony” Williams (1953-1978).

The MCC moved back to the Unitarian building and was largely held together in the absence of an active pastor by committed members like Dan Wilcox (1940-1994), who appealed to local Utah publishers Jack Gallivan (The Salt Lake Tribune) and Wendell J. Ashton (Deseret News) to allow MCC to run advertising space in their newspapers again.

“The religious grounds for discrimination against gays are crumbling as scriptural research on the subject has become more responsible,” Wilcox observed in 1980.

The silent tragedy of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s devastated Utah as hundreds of gay men died in the absence of state and federal action. Dr. Kristen Ries was practically alone in diagnosing and providing care to these patients.

- Dee Bradshaw

- Pastor Bruce Barton, center, and church volunteers offered what aid they could during the AIDS epidemic.

“Thank God for the women,” Bruce Barton (1946-2017) related in an oral history. Numerous local women assisted Barton—who became MCC’s pastor in 1983—to tend to the needs of the sick, whether they were congregants or not.

“We were so limited in what we could provide temporally, but we could provide people,” he added. “We could provide emotional and spiritual support, which I think falls through the cracks.”

Kelly Byrnes, who assisted Barton, relishes the spaghetti dinners, dances, workshops and regional conferences they held in those days. Most of all, he remembers the labors they undertook to support the dying and grieving.

“It was a lot of work, but it was good work,” he said.

Barton ministered to people in the bars rather than waiting for them to come to him. He brought the renamed Resurrection-MCC, for the first time, to a building that they owned outright rather than renting from another. Re-settled in August 1986, this is the location the church occupies today at 823 S. 600 East, SLC.

An Opened World

Cindy Solomon-Klebba replaced Barton in 1994 and, until her departure, she provided continued aid and interfaith efforts to the community. She particularly cherishes the support that the church gave to local Utah high school students in their struggle with the state Legislature over establishing Gay-Straight Alliance clubs (a controversy covered by City Weekly in February 1996 under the Private Eye masthead).

“We’re always going to be on the forefront of justice; that’s what we do,” Solomon-Klebba remarked. “We believe that being Jesus in the world means doing justice to the people in the world.”

- Wes Long

- The Sacred Light of Christ Church, as it stands today

With Solomon-Klebba—and her successor, Dee Bradshaw—the renamed Sacred Light of Christ Church was a fixture at Pride events and even contributed floats for the parades.

Branches of MCC operated in Ogden and Logan concurrently with Salt Lake for several years, but by the 2000s, these additional branches had closed and the Sacred Light of Christ Church broke from the larger MCC Fellowship.

Today, Kay Sidwell and Korina Garcia serve as the new team ministry for the Sacred Light of Christ Church. Having implemented group meetings in person and virtually, they are eager to engage with and serve the community, whether LGBTQ+ or not.

And they are in good company, for much has changed since those earlier years.

Many more religious denominations today are welcoming people of varying colors of the rainbow, Sidwell and Garcia noted, and with increased iridescence comes added beauty, both to matters of the heart and to those of the spirit. Faith and sexuality, in their view, don’t have to be an “either-or” situation.

“Once I came out, the whole world opened up because I wasn’t hiding,” Sidwell related. “I wasn’t hiding part of who I was.”