CQ STORIES with Terry Dunn

A British poet once wrote that “blood is the fragile scarlet tree we carry within us.”

If you take the time to read up about blood, its many vital functions, and how gifts of blood can help the ill and the injured in so many ways, you can’t help be awed.

Arguments can be made about which part of the human body is most important for life. The brain, the heart, lungs, what have you. All are clearly important but, I think, it would be hard to dispute placing blood towards the very top of such a list.

Without an adequate supply of healthy blood, our brains, lungs, other organs and our muscles would lose their ability to keep us healthy and functioning properly.

Donating one’s blood, long known as the “gift of life,” has been a time-honoured symbol of altruism. Before we delve into the topic of blood donation and why it’s so important, it’s useful to have some context, which I hazard to do at risk of upsetting my cardiologist.

The average adult hosts around five litres of blood. For easy, everyday reference, that’s almost two and a half six-packs of beer. A healthy adult can afford to lose one of those fives litres without ill effect – or just about three cans of beer.

There are, in an adult of healthy weight, about 40,000 kilometres of blood vessels. I’ll spare you the usual comparisons of travel distances, save to say that’s about two continuous days’ worth of cruising speed flight on a Qantas passenger jet. If that thought doesn’t cause the blood to drain from your face I don’t know what would.

A kilogram of added body fat requires about 25 kilometres of additional blood vessels. Think about what that means for your heart health the next time you reach for that greasy hamburger with processed cheese, fat-streaked bacon and mystery sauce.

Blood has four components. Red cells, which account for just under half the volume of blood, nourish our body with oxygen inhaled by our lungs and carries carbon dioxide, a waste product, back to our lungs to be exhaled.

White cells serve as policemen and janitors in our bodies, seeking to protect us against viruses and bacteria.

Platelets, like the famous advertisement image of a Dutch boy plugging a water leak in a dyke with his finger, patrol the body looking to stop any bleeding from our circulatory system.

Lastly, half of your blood consists of a yellowish liquid called plasma. Now, at first glance, you might think plasma is there merely to transport platelets, red and white cells, but you’d be wrong. More on this later.

There are many reasons why we might need to supplement our personal blood supplies with a transfusion of either red cells, platelets or plasma, including surgery, injury, illness and disease. (White cells are not transfused due to a risk of an immune reaction.) One in three Australians will need a transfusion at some point in their lifetime. To meet demand nationally, a blood donation is needed every 20 seconds.

Lifeblood is the Australian Red Cross’s national blood donor operation. In Rockhampton the Lifeblood donor centre is located on Murray Street, on the southwest side of the Rockhampton Hospital campus. There are Lifeblood donor centres in Mackay and Gladstone as well.

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit the Rockhampton Lifeblood donor centre where I met Rosie Barton who is the Group Account Manager for the Lifeblood donation centres in Rockhampton, Gladstone and Bundaberg and Paul Miller, the Rockhampton Donor Centre Manager.

All Lifeblood donor centres take donations of whole blood and plasma. Because they have a relatively short shelf-life and need special handling, platelets are only collected in Lifeblood donor centres in metropolitan areas.

The donation procedure is managed by either a registered nurse or a nursing assistant who has been trained to Lifeblood standards. From health screening through actual donation to the complimentary drink and snack at the end takes about one hour. Donating plasma takes about an hour and a half.

One side benefit, upfront, of donating, is that the eligibility screening performed can detect some important medical conditions of which you might not be aware. For example, your pulse with be checked and it may indicate you have an irregular heartbeat. A blood pressure check may show you have elevated or high blood pressure.

The process will also determine your blood type if you don’t already know it. There are four blood types, commonly known as A, B, AB and O (as in the letter oh). This is important to know as one person’s red cells might not be compatible, immunologically speaking, for another person in need of a transfusion.

In addition, you may or may not have a particular blood protein called Rh factor. The presence or absence of this protein is represented by a positive or negative sign, respectively, following your blood type, for example A+ or O-.

According to Lifeblood, the most common blood type in Australia is O+ (38 per cent), with A+ a close second (32 per cent). The least common blood type is AB- (1%).

All donations are checked for HIV and hepatitis B and C. If you have travelled to certain parts of the globe, your donation will be checked for malaria. Lifeblood will notify you if any of these diseases have been detected in your donation.

Another benefit of blood donations for the wider community is the monitoring Lifeblood does of the donation stocks for new and emerging diseases, which can serve as an important tripwire for protecting public health.

Rosie told me, on average, 1000 donations are made every month at the Rockhampton donor centre. Compared against the potential number of age eligible people in Central Queensland, perhaps somewhere around 156,000 souls, well, I’ll leave it to your judgment whether we CQ’ers should be doing a better job of donating blood.

That average, surprisingly, held for much of the Covid-19 pandemic. When restrictions began to ease, the number dropped slightly as Central Queenslanders took the opportunity to travel again to see friends and family.

Once collected, blood and plasma donations are transported by road every day from Rockhampton to a Lifeblood processing centre in Brisbane.

You might think the primary reason for a transfusion is road accidents and other types of trauma but you’d be mistaken. Road accidents and other types of trauma account for only two percent of the reason for transfusions in Australia. Cancer and blood diseases account for over 30 percent of the demand for transfusions.

There are many other important reasons why someone might need a transfusion, including, according to the Lifeblood website, “anaemia; non-orthopaedic surgeries; stomach, kidney and other diseases; bone fractures and joint replacements; and to treat young pregnant women, new mothers and young children.”

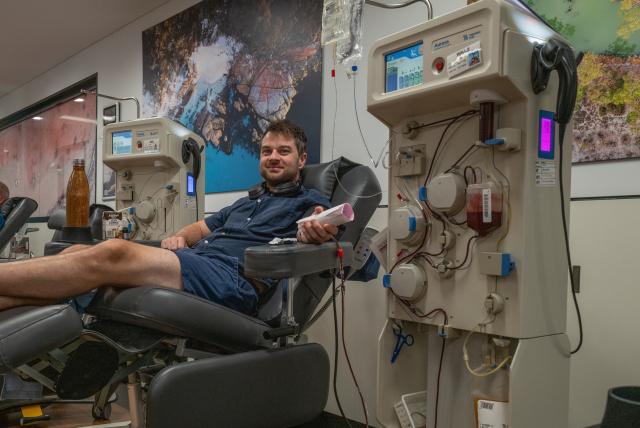

On the day of my visit to the Rockhampton Lifeblood donor centre, about a half-dozen donors – men, women, young and not so young – were lounging comfortably while they each filled a 475mm bag. I asked Rosie about the demographics of donors. She said it’s about evenly split between men, women and age groups, with one notable exception: young men.

Adults between the ages of 18 to 75 are eligible to donate blood. Yet, for some unknown reason, and Lifeblood is doing research on the topic, young men in Australia do not donate as much as other demographic groups. Do young men have an inordinate fear of needles? Are they afraid donating blood will affect their performance on the sports pitch and elsewhere? Are they just busier than others? Who knows, it’s a mystery and one well worth solving.

We need to return to the topic of blood plasma, because it’s a wondrous thing and it’s important to consider making a plasma donation. Plasma has a variety of functions in addition to providing a ride for our blood cells and platelets. It carries hormones and nourishment to our organs and muscles. It helps with repair of injuries. It fights infection and carries away waste for disposal, plus many other tasks important for our health.

When you donate plasma, you are providing an ability to treat 18 different medical problems, including hepatitis B, severe burns, haemophilia, folks needing bone marrow transplants and heart surgery, and immune system deficiencies.

Plasma is also important for pregnant women, 17 percent of whom in Australia will need an injection of something called anti-D to help prevent the mother’s immune system from attacking the red cells of their unborn baby. Anti-D is developed from donations of plasma from the rare individuals who have a particular immune system compound and who are willing to donate plasma.

Rosie said that while there are strict eligibility requirements to donate blood and plasma, it is important that folks not rule themselves out. Lifeblood estimates that as much as 40 percent of the adult population in Australia believe they aren’t eligible to donate blood. Lifeblood staff are very happy to talk with you to determine your eligibility. Chances are, perhaps with input from your GP, you might be able to make a donation.

Check out the Lifeblood website at lifeblood.com.au. It has a wealth of information about blood, donations, current research and the uses to which your donation might be put. There’s a Live Chat capability and you can also book an appointment through the website.

It’s hard to think of a more simple act of generosity, one that takes only an hour or so of your time and yet can make such a difference to someone who needs the donation of red cells, plasma or platelets to recover, to survive or just to live a life as close to normal as possible.

National Blood Donor Week this year will run from 12 to 18 June. So, here’s your chance to make another donation and, if you are a first-timer, to start what I hope is a regular practice of giving the gift of life.