The loss of the Yongala was a tale of tragedy, but out of this has come one of the world’s most-spectacular shipwrecks, which is absolutely smothered in marine life, as Trevor Jackson explains.

Photographs by Julia Sumerling and Mike Ball Dive Expeditions.

There’s a genuine steamships’ telegraph in my lounge room. Salvaged from the depths. It’s in pretty good condition considering the time it spent underwater. Its bells still ring, and on the faceplate, it reads ‘Full Ahead, Half Ahead, Dead Slow, Finished with Engines’. Inside, a series of chains and cogs once connected it from a wheelhouse, to an engine room. An identical telegraph in each room enabled the captain and the engineer to ‘speak’ to each other.

That’s how it was done in the golden age of steam. Famous ships like Titanic and Bismarck had them. Closer to home, Captain William Knight, master of the SS Yongala – now one of the world’s most-fabulous wreck dive – had one beside him. It was the late afternoon of 23 March 1911.

Full Ahead

Knight’s tired face was pressed against a porthole. The sun was just setting across the mountains west of the Whitsunday Islands and the sky had an uneasy tone to it. Something was up. His weathered eyes looked to the east, and a faint hint of concern may have been seen, had anyone astute enough, been in the room. He was a career sailor with decades behind him. He’d seen a thing or two. He’d even lost a ship before. He wasn’t planning on doing that again. But tonight, he was edgy. He cursed the fact that the ship’s wireless he had ordered was still enroute from England. He still had to rely on flag signals from coastal ports, to get an inkling of what the weather was doing. ‘So last century’. Before long, his mind wandered, and his thoughts settled on the loss of the SS Glanworth, 15 years prior.

The Glanworth had hit the rocks near Gladstone, a few hundred miles south. The Marine Board relieved the good captain of his ticket, until public outrage about Gladstone’s notoriously out-of-position lighthouse forced them to reconsider. When starry-eyed passengers would ask him of his adventures, he would open up with the old sailors’ adage. ‘If you haven’t been aground, you haven’t been around.’ He meant it.

After the Glanworth incident, William Knight spent a few years as a first officer, but eventually, fate put him at the base of the gangplank of the Yongala. That, in turn, would lead him to this point – passing Dent Island an hour before dark, the sea opening up to the north and a brisk breeze developing from the south west. If Captain Knight had seen the warning flags when he left Mackay earlier, he might have done the prudent thing and anchored up. But he hadn’t seen them. The Dent Island lighthouse keeper watched the ship pass by at dusk. All seemed fine. Yongala steamed north at ‘Full Ahead’.

Half Ahead

Night fell, and Knight’s concerns began to grow. He didn’t know it then, but Yongala’s chances were fading with the light. A full gale from the southeast kicked off. With the protection of the islands now well behind them, the developing squalls ran rampant in the open sea space. Waves were mounting up to the east of Cape Upstart and the Yongala might soon need to find shelter. But where? By late evening, Captain Knight was beginning to realize that his options had narrowed to nothing. To his port, mainland Australia. To starboard, the coral. He couldn’t turn either way. Caught between a rock and… a rock, let alone a hard place.

His only option was to just run with it, but the further north he got, the greater the fetch behind him. The waves just kept getting bigger.

Down below decks, things were going okay. Propulsion was by a state-of-the-art triple expansion steam engine. In Yongala’s day, this was the equivalent of a moon rocket. Seventy, hand-shovelled tonnes of coal kept the process going in the boilers, each day and night. The coal made the fire, the fire the steam, the steam the movement. Beautiful, efficient, and compared to todays’ diesel motors, whisper quiet. On the night she was lost, the wind would have easily drowned out the noise from the engine rooms. But her stealth didn’t slow her down. This ship could really move. A standard ship of the day might have pulled 12 or 14 knots at top speed. Yongala was regularly clocked at 17. With the mighty gale now pushing her along, she must have been reaching upwards of 20 to get from where she had been, to where she ended up. As the waves built up behind her, things started to get a little out of hand. The ship began to surge forward on the bigger waves, she was to about to start surfing. Uncontrolled speed would mean certain disaster. To steady the ship, and to keep her steering straight, without actually launching down the face of a wave, Knight slows her down. He signals, ‘Half Ahead’.

Dead Slow

Near the centre of a cyclone, you can attest to two things… mind-numbing wind, and zero visibility. The poor visibility is caused by rain, and the rain would become Yongala’s nemesis. With the ship now struggling to keep straight, Captain Knight noticed a lagging in steam pressure. His fires were dying. Ordinarily, no amount of rain down the funnels would have any effect, but Yongala was now in the grim clutches of a cyclone. At this point, Yongala lost a funnel.

As it was wrenched from the deck, a gaping hole left the boilers and engine rooms exposed… Niagara Falls cascaded straight down with predictable results. The fires went out… No fire, no steam, no forward motion…. From then it would be only minutes before the inevitable. The ship turned side on to the waves, rolled heavily once or twice, lost half its deck fittings, went down on its side and never recovered. She down-flooded, capsized and sank. Resistance was futile. No man, woman, rat, horse or bull got off alive.

Moments before that, in a vain attempt to at least keep the ship running downwind while they readied the life-rafts, Knight had reached again for the telegraph. It was a fruitless exercise done more out of habit than logic. The dial clicked over. Dead Slow.

Finished with engines

Well over a century has passed since that night. These days, when you’re out there on the water, it’s a calm winter’s day, all that is forgotten. No-one alive saw the cyclone that sank the mighty ship. No one alive knew anyone on her. All we have now is what remains… but… much more importantly, what has been created.

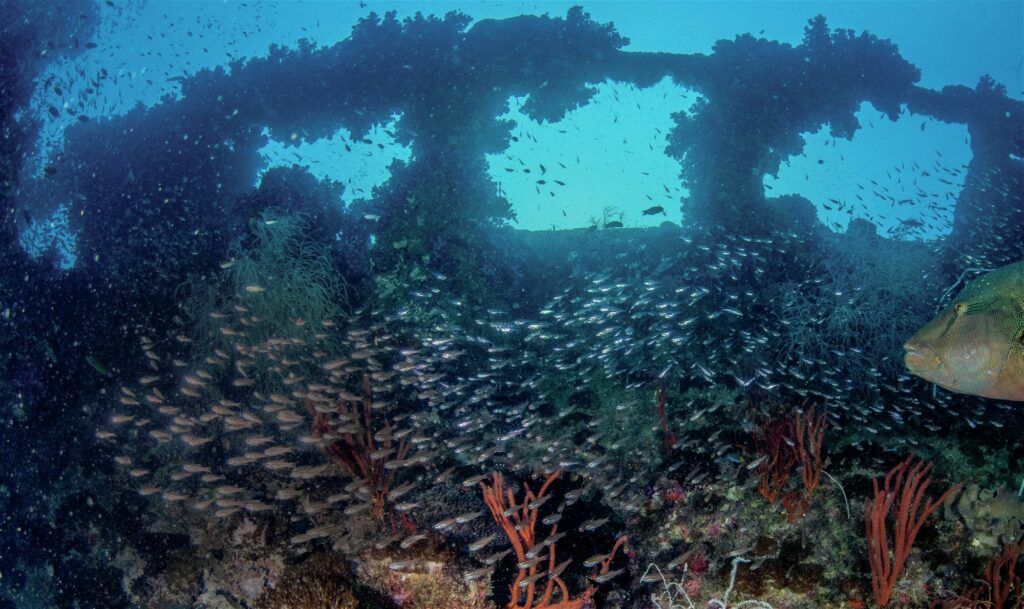

Yongala lies on a patch of sand that stretches 20 miles in most directions. There are no reefs, no rocks, no weed beds…. Nothing at all, anywhere near the ship. Just grey sand and plenty of water movement. Current is the currency of life. Where there is current there is an economy of sorts. Current means you get fed. A nice safe place to sit while you wait for your next upstream meal is even better. There is nowhere, at least in my estimation, that quite matches the wreck of the SS Yongala in this department. She’s a giant apartment building, 30m down, with a constant stream of restaurant-quality food coming its way, free of charge, 24/7. And that attracts, well… just about everything.

To most of the creatures that live on or near the wreck, she is the only home they’ve ever known, the entire universe. There is nowhere else. There’s no mission to Mars to get to the next place. There is no next place. Everything that ever existed or will ever exist, exists here. And if anything new comes along, it stays. The competition to survive is overwhelming. The whole place is constantly electric, frenzied, manic, a symphonic crescendo. It’s like the wreck just can’t help itself. It has to be bigger, better, badder. It’s almost as if she is trying to make up for the 122 souls she took, trying to pay the world back. If you go there, you will see that she has.

The ghost of William Knight is said to still walk the decks of Yongala. But ghosts aren’t real. If they were, I’d like to think of the Captain standing on the port bridge, surveying the unbridled beauty of the place he left behind, all those years ago. He’d see the giant purple soft corals swaying, the marbled rays cruising, the bull sharks rioting. If he listened carefully, he’d even hear the orchestra playing.

He’d reach down, and a weathered old hand sitting atop an old steam telegraph, would move it back, just one more notch. A faint bell would sound as it clicked into place. The ghost of Captain Knight would smile at the treasure that the Yongala has given to the world, and after all this time he would finally be… Finished with engines.

This article was originally published in Scuba Diver ANZ #55.

Subscribe digitally and read more great stories like this from anywhere in the world in a mobile-friendly format. Link to the article