Has it really been 10 years since Ford announced that it would cease making vehicles in Australia?

The actual date, Thursday, May 23, 2013, happened to coincide with the national press launch of Holden’s all-important VF Commodore – Australia’s last-ditch effort to reverse freefalling large-car sales as well as revive exports with the US-bound Chevrolet SS version.

An auspicious date in local motoring history for sure, but for the wrong reasons, since Ford’s announcement signalled the beginning of the end of full vehicle manufacturing in this country, not helped by the VF’s market failure on both counts.

Leading up to the morning that Ford called the snap press conference at Broadmeadows HQ, most journalists might have expected – at worst – confirmation of the slow-selling Falcon’s inevitable demise. Conjecture had started circulating earlier that day predicting far worse, but to many observers, Ford seemed too entrenched in the national fabric to abandon 91 years of continuous production in this country.

By mid-morning, however, as then-president and CEO of Ford Australia, Bob Graziano, stepped up to the stage, his weary eyes and solemn tone betrayed the devastating news he was about to deliver. The reasons, something about unsustainable costs and mounting losses, seemed coldly corporate compared to the shell-shocked faces of employees huddled nearby, their tears already streaming down their cheeks.

In the days that followed, industry analysts talked of more doom, with one union spokesperson stating that for each of the circa-1200 jobs that would be lost at Ford – some 650 in Broadmeadows and 510 in Geelong initially but scores more eventually followed – nine more would go in related support and supplier industries.

The resulting breaking supply-chain base added another whole new level of pressure on the remaining manufacturers, embattled GM Holden and Toyota, and in the ensuing months, they too made The Announcement. The last Australian car – ironically a VF II Commodore – left the production line in October, 2017, some 54 weeks after the final Falcon.

Of course, back in 2013, Ford’s spin on manufacturing withdrawal from Australia came with a host of promises – including more models and increased competitiveness, as well as a return to profitability to help the remaining employees keep their jobs.

Ten years on, let’s see how the brand has fared on those and more fronts since.

Model choice

In 2013, Ford offered 10 distinct models.

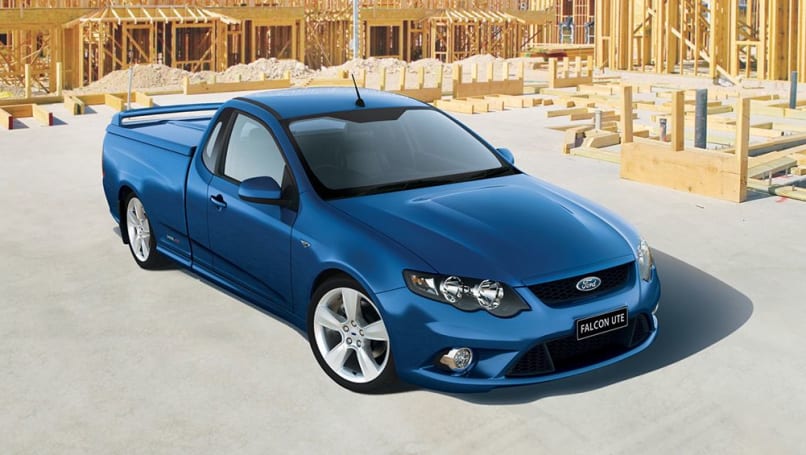

In ascending order of size, they were the Fiesta supermini, EcoSport light SUV, Focus small car, Kuga medium SUV, Mondeo midsized liftback/wagon, Falcon large sedan, Falcon ute, Territory large SUV, Ranger medium truck-based ute and Transit van.

Of those, only two – Falcon and the closely-related Territory – were built locally. The latter is the only Australian-built SUV ever.

A decade on, and the Fiesta, Focus, Mondeo and Falcon are gone without replacement, leaving the Mustang muscle car released in 2015 as the only passenger car in Ford’s line-up today. An understandable development given their decline in popularity, though Toyota, Mazda, Hyundai, Volkswagen and Skoda all seem to make such types of cars still work.

On the SUV front, EcoSport, Kuga and Territory are also history, replaced by the Puma, Escape and Everest respectively – though the Escape is about to exit Australia, likely forever. Ranger and Transit remain and prosper.

Ford’s nameplate count is about to dip down to five, then. This hasn’t happened since the 1960s. So much for choice.

However, the all-electric Mustang Mach-E and very combustion-engined F-150 full-sized truck will usher in some welcome new-model activity by the end of this year, with more EVs expected by 2025. But at very steep prices, further undermining real consumer choice.

Which leads us on to competitiveness.

Competitiveness

The rationale when a company pulls up stumps producing vehicles in Australia is that imported alternatives could often be cheaper and/or better value, due to lower manufacturing and labour costs.

That was certainly the sentiment in the months and years after Ford’s closure announcement, and as long as those passenger-car models like Fiesta and Focus remained on sale, there was a Blue Oval option for most buyers.

The 2020s, however, has all been about scarcity and rampant inflation. Everyone’s affected because of COVID-19 and related production delays, driving prices up across the board. This is news to nobody.

Ford’s decision to ditch both the Fiesta and Focus compacts in Australia, however, now means consumers cannot buy a new Ford for much under $35,000. That would be the Puma from $30,840 before on-road costs, while even adjusted for inflation, the 2013 $15,490 Fiesta CL would still only be about $19,500 in today’s money.

Yet that early talk about cheaper vehicles does seem to ring true when comparing Ranger like-for-like. A 2013 PX XLT 3.2L 4WD auto at $55,390 translates to about $69,700, compared to just $61,990 for today’s PY XLT BiTurbo 4WD auto equivalent.

Still, if you’re on a tight budget, there’s less Ford in ‘affordable’ nowadays.

Employee numbers

Ford Australia says it currently employs around 1800 people – about half the number compared to 10 years ago. That’s still a damn-sight better than the zero workers at Holden.

During the Falcon’s halcyon days at the top of the sales charts of the 1980s, over 9000 people were employed between Broadmeadows and Geelong, with more at other sites like at Homebush in Sydney.

Dealer representation

Approximately 180 Ford dealers operate in Australia today, according to a Ford spokesperson. That’s down from around 200 dealers 10 years ago.

Considering that Ford only sold a (severely production-constrained) 66,628 vehicles last year compared to 87,236 in 2013, that’s impressive.

Profitability

Here’s where it gets really interesting.

Ford reportedly lost $267 million in 2013, nearly double that of the year before but still slightly short of the $290 million deficit back in 2011.

Since ending manufacturing, Ford Australia does not have to reveal such information in detail, but we understand that it is one of the more profitable outposts within the Ford empire nowadays.

There’s plenty of money to be made selling premium-priced trucks and SUVs like the Ranger and Everest respectively – especially when long waiting lists and high demand mean some buyers are prepared to pay extra to get behind the wheel of one.