Travel to Africa generates hopeful expectations for many, if not most, Black Americans. We frequently see journeys to the immense continent as opportunities to imbue our travel experiences with meaningful immersion into our ancestors’ ancient and contemporary cultures.

Culture and history aren’t the only reasons to travel to South Africa, as the country offers a broad range of activities. But under certain circumstances, for certain people, travel here holds greater meaning.

So it was for me as I embarked last week to cover the Indaba Travel Africa trade show in Durban, South Africa. With other journalists, I also spent time in Johannesburg and Cape Town as part of a 15-day journey.

The first few days were filled with new experiences. In Johannesburg only briefly, I enjoyed a panoramic (albeit fast-moving) drive from the sleek Voco Rosebank hotel, through stately suburbs and busy commercial districts, to OR Tambo International Airport.

Days later I found myself strolling the boardwalk at Bay of Plenty Beach on coastal Durban’s “Golden Mile.” I marveled at my first-ever, up-close view of the Indian Ocean.

Later in Cape Town, our group embarked on a winery Jeep tour through three separate wineries (and approximately 15 samplings) in the magnificent Stellenbosch region.

Common Experiences

Yet for me, the trip’s most profound moments were ultimately delivered through cultural sites dedicated to stories of apartheid in South Africa.

Strikingly, the sites link Black South Africans’ persecution and disenfranchisement under apartheid with Black Americans’ contemporaneous struggles for civil rights during the 1960s.

They include Cape Town’s District Six Museum, which chronicles the forced removal of 60,000 residents from the historic neighborhood the facility borders.

Previously a “vibrant community of freed slaves, merchants, artisans, labourers and immigrants with close links to the city and the port,” as described by Museum officials, District Six was declared a White area on Feb. 11, 1966.

Under the Group Areas Act, residents of the multi-cultural coastal neighborhood (which not coincidentally represented some of the city’s most favorable real estate) were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas known as the Cape Flats.

The residents included Susan Lewis, our Museum guide that day, who patiently described her experiences and her previous life as a child in District Six. After their removal, the residents’ homes were flattened by bulldozers.

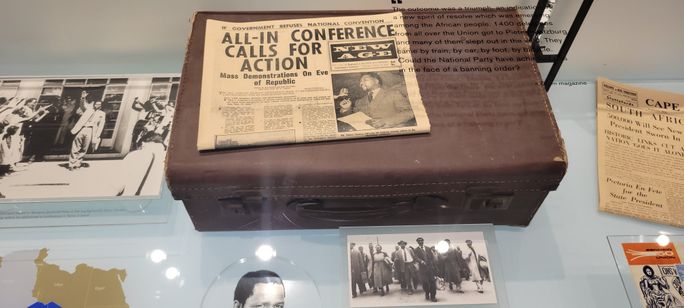

District Six Museum display. (Photo by Brian Major)

An Unforgettable History

The Museum faithfully relates District Six’s wrenching history through original photographs and news articles, maps, personal art and artifacts and colorful full rooms adorned in a period décor.

The Cape Town story mirrors events also familiar to students of the Black American experience, including the dismantling of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania’s Hill District,

The thriving Black community was decimated during the 1950s and 1960s, as 8,000 residents and 400 local businesses were displaced and forced to move elsewhere over two decades.

The Hill District joins New York’s San Juan Hill (razed to build New York’s Lincoln Center) as one of many thriving neighborhoods scuttled via “urban renewal” programs disproportionately targeted toward Black communities.

Ultimately, the District Six Museum delivers an uplifting message. Although not a fate shared by all of the former residents, Lewis was ultimately able to prove her family once lived in the neighborhood, and via a lengthy legal process reclaim a home in District Six.

Display at the Nelson Mandela Capture Site Museum in Howick, KwaZulu-Natal. (Photo by Brian Major)

The Nelson Mandela Capture Site

My South Africa visit ended in Cape Town. While I did not visit Robben Island, the offshore location where Nelson Mandela and his comrades endured decades of brutal imprisonment, the site can be visited via excursion from Cape Town’s Victoria Wharf waterfront.

Beyond Robben Island, I can’t imagine a site more evocative of Mandela’s compelling struggle for freedom than the Nelson Mandela Capture Site Museum.

After 17 months as South Africa’s most wanted fugitive, Mandela was seized by government forces on Aug. 5, 1962 (ostensibly for anti-apartheid acts committed 10 years earlier) at this pastoral countryside spot outside of Howick, KwaZulu-Natal.

Disguised as a chauffeur, Mandela was apprehended while driving a 1959 Austin, a model of which is now on display here. His capture that day began 27 years of captivity for the African leader.

The Museum features a voluminous collection of films, original photographs, art, newspaper articles and personal items ascribed to Mandela and his many colleagues.

The artifacts relate a comprehensive view of the towering African leader who inspired Black people around the world.

The Museum Grounds include a striking statue of Mandela, located at the end of a long stone path symbolizing the many steps the leader traveled over 27 years to achieve freedom and apartheid’s end.

Mandela’s history largely parallels the U.S. Civil Rights movement and inspires Black Americans – and all people – to this day as an example of the power of resistance and dedication to self-determination. It’s just part of what makes travel so rewarding.