Standing on the roof of the old Torrens Island power station, workers can witness Australia’s energy transition being mapped out as far as the eye can see.

The old gas plant – one half shuttered and the other partly mothballed – stands tall alongside a more compact 21st-century version a few hundred metres away.

There’s an old piece of equipment on the upper levels fondly called “the governor” by generations of workers. The governor maintained the generator frequency by controlling the turbine’s steam.

The steampunk-style gears, springs, cranks and hydraulics that link the spinning turbine shaft to the steam valves have been replaced by complex power electronics in wind turbines and batteries.

And as more solar and wind comes online, and millions of households benefit from rooftop solar, excess energy during the day is causing so-called negative prices for the country’s big, old generators.

What this means is that the generators not nimble enough to switch off end up paying to supply the electricity grid, even as they’re burning increasingly expensive coal and gas.

Australia’s biggest energy company AGL Energy has opted to shut down plants earlier than once planned instead of haemorrhaging millions of dollars, and bet on a mix of sources to power homes and businesses.

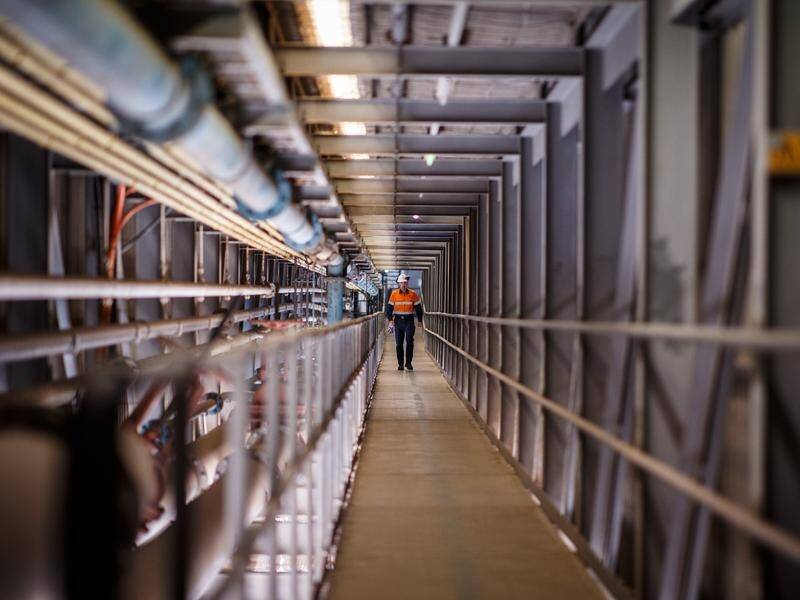

The now-defunct Torrens “A” is linked to Torrens “B” by a passage that workers call the “time tunnel”.

A spaghetti-like maze of old overhead wires connecting the two halves are being stripped out metre by metre as some are still live.

The eerily quiet mountain of old equipment will be taken out and the old plant will be demolished.

Beyond the massive rust-coloured plant is the new $180 million 250 megawatt grid-scale battery that can suck in excess solar and wind energy, store it for several hours and sell electrons into the electricity grid when demand is high.

The batteries have been installed on elevated ground the size of the Adelaide Oval to prepare for a rising sea level, alongside mangroves on the island’s edge where bottlenose dolphins often frolic while engineers and electricians are at work.

As a blueprint for other future industrial hubs, there’s scope on-site for hydrogen and ammonia production feeding off South Australia’s abundant renewable energy close to a deep sea port.

AGL head of gas Kevin Taylor, who started at Torrens in 1986 and has worked at many other places before returning, never imagined the gas plant would be replaced within his lifetime.

“When I started my career, all the power was generated by traditional generation sources like Torrens A and B stations,” he told AAP.

“I would never have considered that technology like wind turbines, solar panels and batteries would provide a large proportion of our needs.”

Torrens B, in the industrial heartland of Adelaide will go quiet, by 2026 – a decade earlier than once planned.

But there won’t be a dramatic smoke stack collapse, because no one wants them falling across the gas lines that crisscross the site.

The energy giant is in a major reinvestment phase and can pay for its clean growth to 2030 according to UBS energy analyst Tom Allen, addressing a key concern ahead of the AGL’s next Investor Day on June 16.

Even if wholesale electricity prices fall, AGL can manage the $3 billion development pipeline and achieve robust returns, Mr Allen said.

AGL’s plan to add up to five gigawatts of renewable and firming capacity this decade could also improve its environmental, social and governance (ESG) profile over time.

It could potentially attract a “scarcity premium” as one of the few large Australian companies able to materially influence the country’s energy transition, Mr Allen said.

AGL would also benefit from gas price caps being extended to July 2025, he said, lifting its valuation to $9.60 a share from $8.05.

The 250MW Torrens Island battery, built by Finland’s Wartsila, will be fully commissioned and handed over to AGL within months after final tests. There’s an option to expand fourfold to four hours of storage capacity.

A short stroll away is the island’s Barket Inlet Power Station, or BIPs, which has decades to run after plugging into the grid in 2017. It fires up to cover morning and evening peak demand, or if renewable generation is running low.

The shiny plant contains rows of 12 separate 18MW units fired by gas or liquid fuel and it’s as warm as a hothouse inside the plant’s building. There’s an option to extend it with a “BIPS B” but not anytime soon.

AGL chief operating officer Markus Brokhof told AAP a precondition would be to convert it to hydrogen.

But he expects ongoing demand for peaker plants – plants that can quickly switch on smaller amounts than traditional power stations when there is high demand during peak periods – as coal power stations leave the electricity grid because existing battery technology can only store energy for a few hours.

However, Mr Brokhof is urging regulators to reconsider costly requirements, such as the so-called harmonic filter, to smooth out voltage fluctuations.

Demanded by regulators between the Torrens batteries and the grid, AGL is in the same stoush with AEMO over a grid-scale battery planned for Broken Hill.

“I see this adding additional costs but also delaying the project, which is not good,” Mr Brokhof said.

“AEMO needs to have a better understanding of what is needed.”

AGL initially wanted to mothball the Torrens Island B plant sooner, citing significant and costly maintenance to keep it operating until 2026.

But regulators warned switching it off before an energy interconnector could link the state’s power grid with NSW would expose SA customers to the risk of blackouts.

“The South Australian government therefore negotiated an arrangement which ensures the Torrens Island Power Station remains in service until mid-2026, when the interconnector is due to come online,” a government spokesperson told AAP.

The licence condition requires a payment from SA Power Networks to AGL, reflecting maintenance costs of $19.5 million, without which AGL says the continuing operation of the “B” unit would be uneconomic.

As a result, likely power reliability for the state will be above the reliability standard “for all but 0.002 per cent of the time” until at least 2029/30, the spokesperson said.

“This is better than NSW, Queensland, and Victoria,” they added.

Billions of dollars worth of other energy security projects are in development in SA over the coming decade.

In the meantime, the new “peaker” gas plant on the island can power up in five minutes – rather than 16 hours – to meet peak demand.

Under existing national energy laws, the energy regulator’s top priority is to keep the lights on.

But Australia’s energy ministers have agreed to put emissions reduction objectives into energy laws for the first time – making coal and gas generation even less viable.

Australian Associated Press