Liam Lynch was killed by the Free State army in the Knockmealdown Mountains in Tipperary on April 10th a hundred years and one month ago.

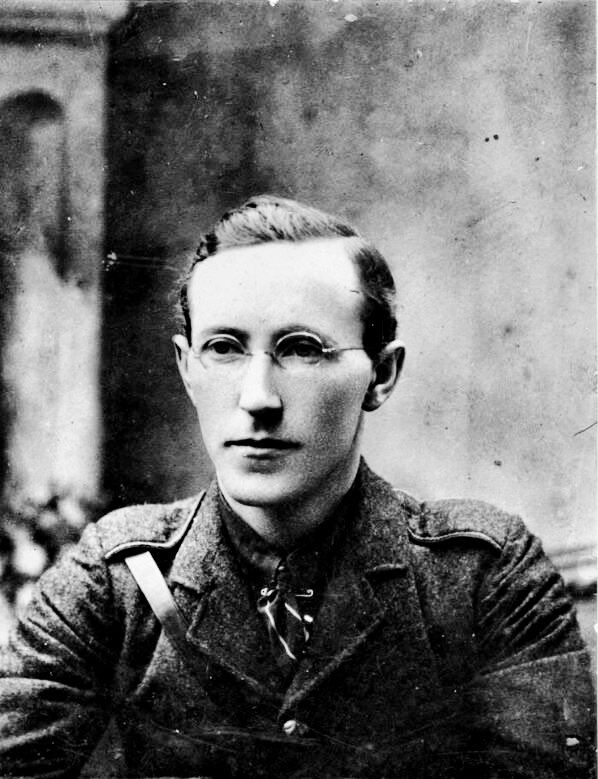

Lynch, a political purist and sincere idealist, was the leader of the Republican insurgency in the Irish Civil War.

After his death, Frank Aiken and other leaders of the anti-treaty forces realized that they could not win against the superior government army and that a clear majority of the Irish people opposed the killings and industrial mayhem of the war.

So, following the old Irish proverb that it is better to quit early than hang in for inevitable defeat, they ordered their forces to dump their arms on May 24th, 1923.

Liam Lynch.

Commentators look back on the eleven months of ferocious civil warfare as a time for deep regret. Some actions by both sides exceeded the savagery associated with the hated Black and Tans and Auxiliaries during the War of Independence which immediately preceded the internal conflict.

Around 1500 people were killed during battles and ambushes, especially in Munster, Connacht and during the early months in Dublin. For balance, historians point out that the civil war in Finland, which occurred around the same time, resulted in more than 20,000 deaths during a shorter time frame.

In Finland, however, Russians and Germans were drawn into that war. In Ireland, there were no outside forces, although England openly applauded the Free State and threatened to intervene early on if the leaders of the new government allowed the continuing occupation by dissident Republicans of the Four Courts building in Dublin.

When Michael Collins, a reluctant negotiator, and Arthur Griffith, returned with the signed Anglo-Irish Treaty in December, 1921, they knew that the document would cause consternation with many of their colleagues in Dublin.

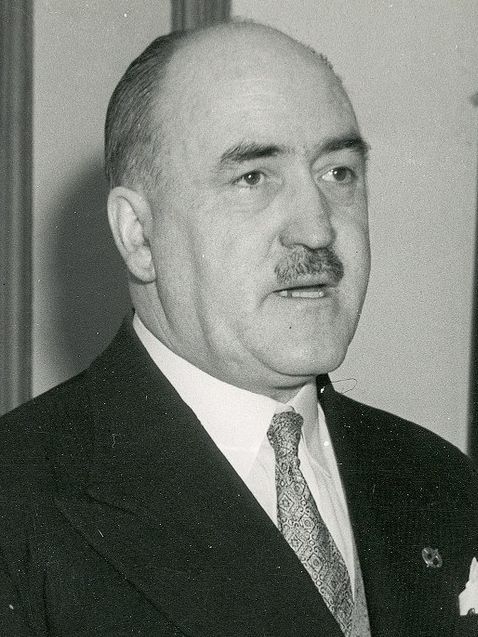

Eamon de Valera.

Eamon de Valera, president of the Sinn Fein executive, angrily rejected the deal as a sellout, and he was supported in the cabinet by Austin Stack and Cathal Brugha. The others followed Collins and Griffith and voted in favor. A 4-3 cabinet split was an ominous result.

Next, the full Dail, all members of Sinn Fein, had the final say on acceptance or rejection. These representatives were all elected in the greatly expanded electorate in the 1918 British General Election. Sinn Fein, under the direction of Michael Collins and Harry Boland, selected activists as their candidates, men and women with strong nationalist credentials, many of whom were active in the growing independence movement inspired by the insurrection in 1916.

These were the people who would decide the fate of the treaty negotiated in London. The main argument of the anti-treaty side centered on the issue of sovereignty. How could Ireland claim success while acknowledging the English monarch as the titular head of an Irish government? They accused the negotiators who signed the treaty of being duped by British Prime Minister Lloyd George, the “Welsh Wizard,” a man known for his duplicitousness.

The oratory in the Dail debate was bereft of magnanimity among colleagues who shortly before had fought the British forces to a standstill. Those opposed to the deal pleaded a clash with their bedrock Republican principles, so no argument about achieving half measures moved them. Only the establishment of a poorly-defined republic passed their litmus test for success.

Collins and Griffith made a powerful case that the document they signed should be seen as a steppingstone to greater freedom. The new state would have the same level of independence within the British Empire as Canada and Australia. Collins argued fiercely that it provided vastly better provisions for self-government than any of the Home Rule bills that dominated Irish politics since William Gladstone in the 1880s.

Frank Aiken.

The Treaty was narrowly approved in the Dail by 64 yeas to 57 nays. A subsequent vote to elect a president of the assembly resulted in a mere two-vote defeat for de Valera, who had promised, if elected, to pack his cabinet with opponents of the treaty. So, democracy prevailed in the parliament, but outside the walls the story was developing very differently.

About two-thirds of the IRA volunteers who fought the war against Britain opposed the terms of the treaty. Many bought the idea that they had sworn an oath to the Republic, a symbolic commitment to an imaginary outcome involving – as they saw it – a democratic parliament legislating for all the people on the island.

This ideal Republic faced a major problem in the North where the Stormont government was set up in 1920 by Westminster’s Government of Ireland Act. De Valera had accepted this reality and even hardline Republicans did not propose an invasion of the North.

Michael Collins was very worried about the terrible plight of Northern Catholics who were subject to nightly pogroms by violent Orangemen. While sending arms to bolster the nationalist resistance, he also met with the prime minister in Stormont, James Craig, to demand amelioration for the frightened Catholic families in Belfast and Derry.

De Valera, despite some incendiary speeches condemning the Treaty, did not support a civil war. The first Dail election in June, 1922, showed clearly that the people wanted the gun and bomb out of Irish politics. However, Liam Lynch and other diehards felt that they were fighting for a sacred cause and emotional speeches on both sides poisoned the political dialogue and led to outrages impossible to justify.

For instance, on March 6th, 1923, five government soldiers were killed in a Republican booby trap in the village of Knocknagoshel in County Kerry. In retaliation, the day after this atrocity, nine Republican prisoners were taken from Tralee to a crossroads at Ballyseedy, a few miles away. They were selected because they were deemed “fairly anonymous, no priests or nuns in the family, people that will make the least noise.”

When they reached Ballyseedy, they were tied around a landmine and blown to smithereens. Amazingly, one man, Stephen Fuller, was driven clear by the blast and lived to tell the story. He later served as an elected member of parliament.

The civil war left a trail of noxious bitterness that permeated Irish politics for a long time. People were defined by the side they took in the awful conflict. De Valera founded Fianna Fail in 1926 and his party came to power in Dublin in 1932. The lineage of the other big party in the Dail, Fine Gael, goes back to the pro-treaty tradition.

The old animosities caused by the pre-eminent issue of acceptance or rejection of the Anglo-Irish Treaty a century ago have receded almost to oblivion over the decades. So much so that after the 2020 general election in Ireland the leaders of the two civil war parties came together to form a coalition government for the country, an administration which is still in power.

Gerry O’Shea blogs at wemustbetalking.com