I had thought traversing the vast, remote, waterless deserts of Australia would be the hardest part of my journey across the country with camels, but now I was facing a completely different challenge: traffic. This was the worst of the busy roads I had encountered thus far – a winding, narrow road with a speed limit of 80km/h that climbed a hill leading to the outskirts of Lismore in the Northern Rivers region, New South Wales. I only had one more week of walking until I reached the most easterly point of mainland Australia, Byron Bay, and the shores of the Pacific Ocean, the end goal of my trek across Australia.

I hugged the far left of the road, pushed up against a guardrail that squeezed me and my five large camels between speeding cars and a steep drop below. The scene was quickly becoming more chaotic. Just as we had begun our ascent, the UHF radios my partner, Jimmy, and friend, Keirin, had been using to communicate with one another and direct traffic safely around the camels had gone flat. Jimmy was running ahead of my slow-moving camel string, his shirt drenched in sweat as he rounded the blind bends in advance, frantically waving his arms to slow the speeding oncoming traffic. Keirin was driving at a snail’s pace up the hill behind me and the camels. Attached to her ute was a yellow “Traffic Hazard Ahead” sign – a futile attempt to stop cars from passing me on the narrow bends.

Long periods of walking alone had bred in me a fierce independence.

Without communication between my two-person support crew, neither knew when it was safe to let cars pass. Drivers were becoming impatient and overtaking with complete disregard for my nervous animals; at times their legs were only inches from the wheels.

I turned my head to check on my camel Jude, who was second in position; his eyes were wide with terror. I could see a truck approaching from behind. Jude could hear it too. He was panicking, twisting sideways, a dangerous habit he had developed that pulled the three camels behind him into the middle of the road. With me up the front gripping the lead rope, I found it virtually impossible to control the 12m of fishtailing camels stretched out behind me. I was tense with fear, praying for the cars not to hit them.

Related: Australian Geographic Society Gala Awards 2022: Spirit of Adventure, Sophie Matterson

Related: Australian Geographic Society Gala Awards 2022: Spirit of Adventure, Sophie Matterson

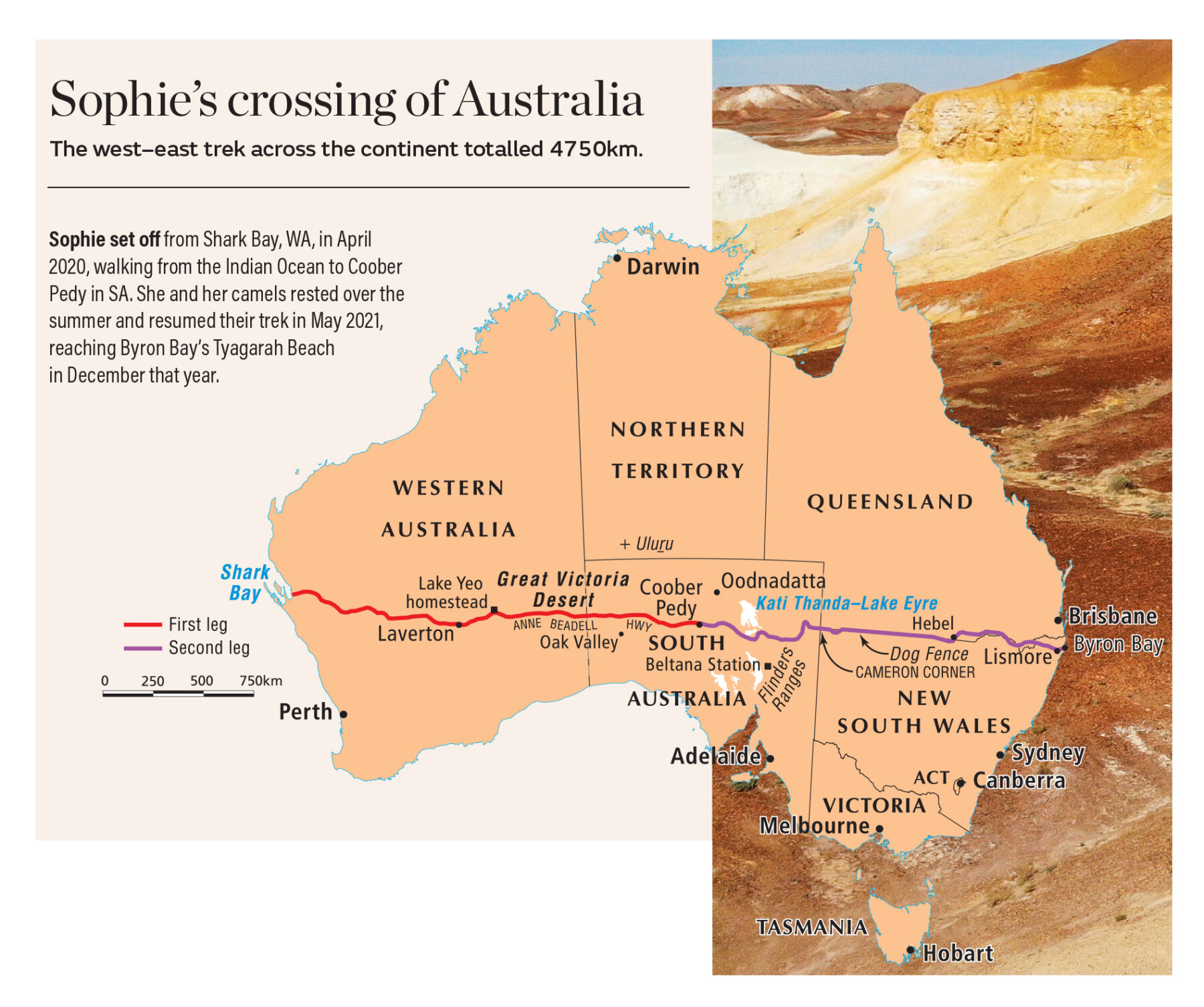

Many camels and I had been on the road (predominantly dirt tracks) for 13 months. We had left Shark Bay on the coast of Western Australia in April 2020, by chance timing the beginning of our journey with the COVID pandemic. Most of Australia went into lockdown. The tracks and roads were deserted, and I often walked for weeks without seeing a soul. In 2021 the second half of my journey proved to be completely opposite to my first.

The extreme summer heat in the outback made walking near impossible, so I chose to split my trip over two years. When I finished the first half in Coober Pedy, I agisted my camels on a station in the Flinders Ranges in South Australia, and flew home to Brisbane. It was strange to not have my camels constantly by my side, and disconcerting living under a roof again where I felt disconnected to the natural world around me. I consoled myself by eating copious amounts of ice-cream, trying to put on weight for the second half of my walk. Drought and poor feed across most of WA had taken its toll on my camels and I hoped they were eating as well. When I returned in early 2021 to muster them from their holiday, I was relieved to be met by transformed, healthy-looking animals. Summer rains had created a buffet of plants – the equivalent of camel “ice-cream” – in the outback and their humps were mountainous with fat.

I resumed my trip in Coober Pedy, where I had left off, and began my long walk to the east coast. I was nervous once again to start, fearing the long break had turned me soft. Could I be as tough and courageous as I had proven to myself during the first half of the journey?

Once again, I settled into the quiet, rhythmic nature of travelling with the camels.

The red gibber stones were painted green with a thick carpet of prickly, but succulent, burrs. I was following the Oodnadatta Track around the south end of the impassable Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre towards the Dog Fence, which runs along the Queensland–NSW border. Rain from the previous evening had left the clay soil below the gibbers soft, and the camels were creating deep sinkholes in their wake. My boots were now four times as heavy as usual, with a tall platform of clay stuck to the soles. We moved closer to the graded track, where the firmer soil made the walking easier. Since lockdowns had lifted, and with international travel still off the cards, it seemed that “every man and his dog” had escaped the city and were visiting the outback.

On my first day walking the Oodnadatta Track I passed more four-wheel-drives and caravans than I had in my entire first six months walking. The response from travellers was amazing. People pulled over to ask me questions, wish me luck and meet the camels. Jude, Delilah, Charlie, Clayton and Mac got used to being objects of attention and adoration.

Although the first half of my journey had been more isolated, there were also many invaluable meetings. Among them was an ex-sniper who helped me with my rifles and prepared me for encounters with wild bull camels, and the Oak Valley Indigenous ranger team that had done water drops for me and my camels in the Great Victoria Desert. But long periods of walking alone between such meetings had bred in me a fierce independence. One of the attractions of my adventure was that with camels I could be self-sufficient – able to travel the country without need of a vehicle support or a team of people. The trip had been empowering in showing me how capable I was of survival in the bush on my own. But as I made my way across the country, I was also beginning to realise that it was the people that I met along the way who had lent so much colour and happiness to the journey.

“Aren’t you worried about weirdos?” had been one of the most common questions I was asked before departing on my camel trek. This question was born of outback Australia’s reputation for harbouring serial killers, the likes of the movie Wolf Creek. Having walked across the continent alone as a woman it now seemed ludicrous. I had met lots of quirky characters, but none that had sinister intentions in any way. It was quite the opposite; everyone was determined to help me. People invited me into their homes, fed me, helped me fix equipment, shared their knowledge, provided hay for my camels. Many became great friends, whom I would one day return to visit. I had even met my partner, Jimmy, on my summer break in the tiny town of Copley, population of 83, near where the camels had been agisted. Jimmy was determined to assist me, driving back and forth thousands of kilometres to deliver food and spend time with me when I took a break.

After Jimmy departed from one such visit in the Strzelecki Desert, I crossed paths the following day with John Elliott, a fellow camel trekker who was walking with his camels from east to west. I then carried on to Cameron Corner, a general store and outback destination that marks the meeting of three states – SA, NSW, and Queensland – where a party was being held with station owners from the surrounding district, many of whom I had already met on my walk through the area. Who would have thought the Strzelecki Desert could be so social!

It was impossible not to be buoyed by the excitement from the public.

Despite the increased sociability I experienced during the second half of my trip, the outback remains a remote swathe of country and I spent many days and weeks alone with my camels. Along the Dog Fence that runs east–west between Queensland and NSW, I saw no-one. I wasn’t travelling a public road, nor did this route take me past homesteads. Once again, I settled into the quiet, rhythmic nature of travelling with the camels. At the beginning of my journey I always felt like I was in a rush (why, I don’t exactly know). I was fixated on the number of kilometres I was doing every day, trying to doggedly to push forward to the end. In this remote part of the country, I gradually became aware that I had finally learnt to relax. I was lingering, not wanting the journey to end, thoroughly enjoying every day with my camels. I was in an area known as the Bullagree, a vast dry swamp with golden dunes created by run-off from the Bulloo River. This time, spent alone without the stimulus of society, made my system slow down. I felt more in tune with nature than I ever had before. I felt free, observing both the infinite space around me and the minute details of nature, the tracks in the sand, the tiny finches and wrens darting between shrubs. When I slept at night I felt as if I could hear the heartbeat of the land itself.

Related: Crossing Australia solo on the camel trek: Sophie Matterson

Related: Crossing Australia solo on the camel trek: Sophie Matterson

As I stood atop a dune in the Bullagree, feeling the wind in my face and watching my camels graze peacefully as the sun set, I realised it was all about to change. I had been looking at my map and noticed that I wasn’t far from where the topographical lines that marked the dunes ended. There was no more desert country standing between us and the east coast. I felt a pang of sadness.

A month later, when I left the small town of Hebel on the Queensland border, I realised I had now not only left the desert, but the outback as well. In front of me were bitumen roads and fences either side. I was used to camping where I pleased, but now I was forced to camp wherever I could find an easement next to the road where my five large travelling companions wouldn’t be so conspicuous.

By now we had moved into grain country and the harvest was in full swing. I spent several weeks weaving between a highway plied by frequent trucks and an overgrown service road next to a trainline.

My five camels had been mustered from the wild. It had taken time but they were now well settled into domestic life, but elements such as trucks and trains were still completely foreign and terrifying for them. There was nothing I could do except expose them to these new experiences and hope that they would be able to get used to them before we reached bustling Byron Bay. They did improve, except for Jude, who remained fixedly scared of trucks. My annoyance at his irrational behaviour was counterbalanced by my deep love for him; he was my favourite camel.

If I had been dreading the isolation of setting off into the desert – before I realised how beautiful it would be – I was now dreading the built-up eastern fringe of Australia. I loved being alone and self-sufficient. But now, dodging trucks and trains, I realised it was only going to get worse and I needed help.

It would be dangerous to tackle the final busy leg to the coast without a support crew to keep my camels safe. And the camels’ safety and welfare had always been my number-one priority. Jimmy and Keirin stepped up to help.

Luckily, that day, on the outskirts of Lismore, we reached the top of the dreaded winding road safely. Jude’s panic was quelled by some emotional eating, and that night we charged the UHFs. In the days that followed, my support crew became professionals, directing cars safely around me and the camels like qualified traffic controllers in hi-vis vests.

I had the easy job; all I had to do was hold on to the lead rope and keep slowly plodding along at the camel pace of 3km/h – you can’t rush camels!

I watched in amazement one day as Jimmy ran out into traffic, holding his left hand up with authority, signalling oncoming cars to stop while waving through 50 vehicles that had come to a standstill behind me. I could see people holding up phones and filming us through car windows, while others yelled encouragement or gave us the thumbs up. It was impossible not to be buoyed by the excitement from the public. We were certainly an unusual spectacle on the outskirts of Byron Bay.

My trek proved I could dream of a great adventure, and have the resolve to see it through.

When I finally caught sight of the Pacific Ocean gleaming before us, it took me by surprise. We had been so focused on navigating the traffic that the end had crept up on us. My trip taught me to compartmentalise, to focus on one day at a time; in that way, such a long journey became manageable. I had stopped thinking of the end long ago, and the sight of the water now took my breath away.

When I reached the water’s edge the following morning, it felt as if time stood still. I let the waves lap at the camels’ toes and looked towards the lighthouse, watching the rays of the rising sun shine between a gap in the clouds and shroud us in purple light. It was magical indeed.

But as friends and family congratulated me, the knowledge that I had yet to safely navigate the camels back through the heavy traffic of Byron to The Farm, where there was a paddock for them, weighed heavily on me.

The main road into Byron was bumper-to-bumper traffic. As well as Jimmy and Keirin, other friends joined me for this final walk. Once we arrived at the paddock and the gate was latched behind us, my entourage erupted into screams and shouts of joy and celebration. They had escorted me safely.

I could no longer hold it together; emotion overcame me, and I sank to the ground in tears with the lead rope still clutched in my hand. My camels and I had made it – we had walked 4750km across the country.

My trek proved that I could dream of a great adventure and have the resolve to see it through. The journey was undertaken as a solo endeavour, and through it I had learnt the strength of my own independence.

However, I realised that without the kindness of strangers, and support of friends and family, it would have been near impossible. The outback tested my resilience, revealed its beauty to me, and showed the generosity of spirit of people I had met along the way.