With as many as 60 additional environmental impact statements, or EIS documents, expected to be lodged in New South Wales over the next year to 18 months, the state’s strategy to replace coal generators is gaining momentum.

Environmental impact statements are documents which outline the impacts of a proposed project on its surrounding area and are put on public display via government portals for assessment before projects are determined.

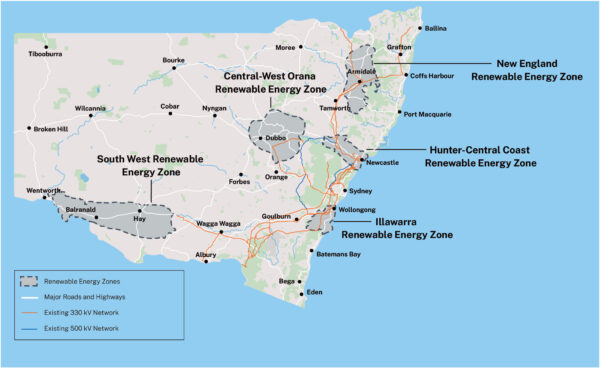

New South Wales (NSW) is not the only state experiencing an acceleration in its renewable energy rollout, but with its dense population, entrenched agricultural industry, and Renewable Energy Zone-based design, it is already encountering pronounced community frustrations.

Image: EnergyCo

It is worth reiterating here, these 60-odd proposed projects sit not only within the five renewable energy zones (REZs), but pertain to endeavours across the entirety of NSW.

While the intention of EIS documents is to make clear to the general public precisely what projects will involve, these documents tend to be exceedingly long and are often complicated by jargon and technical details.

Moreover, it can be difficult to quantify the information they contain, including traffic and environmental impact assessments. Most renewable energy projects are proposed in regional and rural Australia, where there is more access to land. Given how small some rural councils tend to be in Australia, they are often limited in their capacity to make informed comments on projects and judge their costs and benefits, Warwick Giblin, who advises local governments on renewable energy projects and is an Adjunct Professor at the University of New England, previously told pv magazine Australia.

As a result of lobbying, the NSW government recently acknowledged the strain this influx of renewable energy proposals is putting on councils within the Central West Orana REZ, awarding the Warrumbungle, Dubbo, and Mid-Western councils an additional $250,000 per year for next seven years to help resource this additional load.

In NSW renewable energy generation projects are defined as State Significant Developments (SSDs). Projects such as major transmission lines are deemed State Significant Infrastructure (SSI). While local government has an opportunity to examine the adequacy of EISs for both types of development, SSI projects are in effect mandated by the state government and there is limited scope for councils or the general public to overturn such a development.

Councils have a bit more power when it comes to State Significant Developments like renewable generation in that they can choose to support, remain neutral or oppose projects. If they choose to oppose such a project, determination is deferred to the Independent Planning Commission of NSW. Projects are also directed to the Commission if more than 50 public objections are lodged in response to the EIS.

Image: courtesy Michael Daley MP

The newly-minted NSW Energy Minister, Penny Sharpe, addressed the ‘public interest’ issue at the ESG Summit held in Sydney earlier this month, saying: “We have to be able to answer the question asked by communities hosting projects like new renewable energy infrastructure: ‘What is in it for us?’”

“The success in being able to answer that question, to be able to communicate the need for urgency of action and to have the right policy, communication and support in place, will determine how quickly these projects can be delivered,” Sharpe added.

In this address, the minister also spoke about social licence, an issue increasingly tied to the energy transition, noting projects which lacked social licence risked slowing the energy grid’s decarbonisation.

A lack of social licence, of course, spans many business enterprises. What is unique to the renewables industry is how much, cumulatively, these projects will shape the physical landscape of regional and rural Australia, especially within renewable energy zones.

Image: Darren Edwards

“This will be the biggest change in this region, on the landscape, since white men turned up with sheep in the 1840s,” Sam Coupland, Major of the Armidale Regional Council which falls within the New England Renewable Energy Zone, previously told pv magazine Australia. “It fundamentally changes everything.”

In theory, project EIS documents are supposed to assess cumulative impacts of projects within a region. This assessment currently falls to project developers – something Giblin has described as questionable.

Developers, Giblin noted, are working within a competitive free market environment, so by nature they are limited in the information they can access about competitor’s projects.

Rather, Giblin thinks the assessment of cumulative impacts should fall to the NSW Department of Planning and Environment, which has a mandate for regional planning.

“It needs whole-of-government planning to address cumulative impacts and to deliver social services and benefits to these rural communities,” Giblin said.

In the current structure, cumulative impacts tend to be inadequately assessed, according to Giblin.

In terms of project’s social impacts, there are now substantial social impact assessment, or SIA, guidelines in place for standardising EIS documents. Even with these in place, converting assessments into actual tangible benefits for communities remains a challenge, according to Giblin.

Giblin feels few projects to date have managed to deliver or promise tangible benefits for host communities, resulting in communities still struggling to see why they should host projects.

Given the state government has decarbonisation targets to meet and renewable projects have investors to answer to, there is a growing impetus on solving issues around social licence.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: [email protected].