Flown out of Palmdale International Airport lately?

Or maybe you found it more convenient to book a flight out of DeMille Field?

In your dreams — and in our past.

In the handful of years between the end of World War I and the 1929 stock market crash, Los Angeles became, lickety-split, the aviation capital of the nation. As California historian Kevin Starr wrote, a third of the country’s air traffic operated out of the 50 local private airfields that put wings on the City of Angels.

The Times, which led the campaign to make that happen, decreed that the city was “air-minded.”

Air-minded? L.A. was air-mad, air-insatiable, thronging any rollout of a new airplane, any air rallies, any new air field.

In 1910, the wide open spaces of Dominguez Hills hosted the first major aviation meet in the United States, and a quarter-million people, half the population of L.A. County by the numbers, turned out. Barely a month after V-J day, in 1945, the county was eagerly proposing 27 new airports, including three or four in Pasadena for Rose Bowl and Santa Anita racetrack visitors.

Most of those, of course, never got built, but where did the actual airfields go, and what replaced them? We do still have choices, if not an abundance of fly spots.

Free-associate the word “airport,” and your head probably goes nonstop to LAX, Los Angeles International Airport — and then zips right on to several pungent adjectives that good taste prohibits us from publishing.

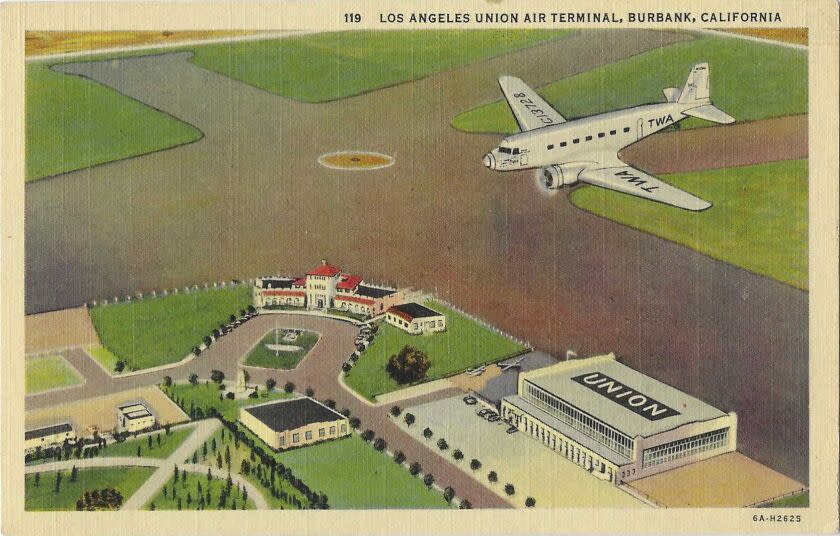

Then Hollywood Burbank Airport, around since 1930. It is still legally named Bob Hope, after the entertainer, and not, to my perpetual surprise, for the aviatrix who helped to put it on the map, Amelia Earhart. Even after the rigors of 9/11 TSA security, BUR still feels like the mini-mart of airports, a place where you can just roll into in your jammies.

Long Beach Airport, LGB, beloved of Yelp reviewers, is also a hundred years old (but not looking a day over 50, dahling), local and cozy — and with a pretty darn striking outdoor garden concourse.

Ontario International in San Bernardino County — forgot about that one, didn’t you? — is century-aged too, and ONT earned its international status thanks to flights to and from Taipei. In 2016, locals took over control of ONT from LAWA, the city of L.A.’s airport agency. For 10 years before that, it was called “LA/Ontario International Airport,” so passengers wouldn’t panic, thinking they were landing in Canada.

And John Wayne Airport in Orange County; it was, until 1979, just Orange County Airport. Your baggage tag will read “SNA” for Santa Ana, the county seat. That makes two major regional airports named for conservative actors. Rumblings are afoot to change the “John Wayne” name. Orange County’s Board of Supervisors re-christened the airport name 11 days after Wayne died, in 1979. (A few months before, there was a proposal to name LAX for Wayne, which went no farther than a baggage handler can throw a 50-pound piece of Samsonite.)

The “Bob Hope” name nudged aside in favor of Hollywood-Burbank because, face it, the names Wayne and Hope are geographically unhelpful — where is “Bob Hope” or “John Wayne”? — and now probably demographically unhelpful. Anyone who was a toddler when Wayne died is over 40.

And oh yes! Palmdale, once imagined as the other LAX, the airport of the future, up there in the high desert. About 90 years ago, it too was just another airstrip on the L.A. aviation map. After several pink-slip owners during and after World War II, Palmdale began to be coveted by the city of L.A. in the early 1970s. L.A. was dazzled by a dream of an array of regional airports. Why, “Palmdale Intercontinental Airport” could turn out to be such a winner, with high-speed trains running in and out of the L.A. basin, that LAX might just close down.

Well, that plan came to naught too. L.A. bought up lots of land, but evidently not enough. A big land rush in anticipation of an airport saw parcels subdivided into smaller parcels and sold off, some to people overseas who were counting on a land rush, and whose ownership wasn’t even registered. Over the decades a few passenger airlines would shuttle people in and out of Palmdale, but nothing ever really caught on.

By 1983, a passerby could spot sheep grazing on the would-be runways. It was a bad sign when the city hired an “agricultural land developer” for the site. At last, 10 years ago, the city of Palmdale took over the rudder from the city of L.A.

Of that longed-for empire of the air, Los Angeles World Airports has now only LAX and Van Nuys airport, which started life in 1928 as a business venture called Metropolitan Airport. It was drafted into service for World War II, and at the government’s big post-war assets sale, the city of L.A. bought it for $1. It changed its name to San Fernando Valley Airport, then changed it again in 1957 to Van Nuys Airport.

Because it’s the city’s general aviation airport, official and emergency aircraft use it as a base, as the California Air National Guard did for decades.

You know who else uses it as a base? Private plane owners and travelers, most egregiously celebrities who treat it like their own two-jet garage. The Kardashian-Jenner clan just got some bad press for flying in and out of the place from its West Valley compound and creating a literal stink in the neighborhood.

Across L.A. County are general aviation airports that you probably haven’t heard of unless you live nearby, in which case you probably hear them clearly, in places like Compton, Torrance, LaVerne, Pacoima, El Monte, Lancaster, Agua Dulce, and Catalina Island.

Santa Monica’s airport, SMO, home port for a lot of celeb pilots, was born in 1924 as Clover Field, named for one of those daring young men in their flying machines, and it was the proving ground for hot new aircraft from local manufacturers whose names you may recognize, like a little undertaking called Douglas Aircraft.

But the sand is running fast for SMO. It has five years left before it starts closing down. The airport property takes up just over 4% of the city’s acreage, and as neighborhoods began to close in, neighbors took exception to the noise, the pollution, and the occasional smashups. Harrison Ford crashed his plane on a nearby golf course in 2015. The FAA wanted the airport to stay in its aviation network, but eventually agreed to the divorce. You’re probably thinking that all that land looks pretty lip-smacking to a city of where the median price for a house is north of $2 million, but the property is pledged to open spaces and public.

HHR, Hawthorne Municipal Airport, birth name Jack Northrop Field for the aviation pioneer, has SpaceX operating at its edge, which explains Hawthorne’s most famous commuter, SpaceX owner Elon Musk. A young man who amused himself on Twitter by tracking celebrity jets has reported that Musk has often flown the six miles from LAX to Hawthorne, rather than take what amounts to a 10-minute car trip.

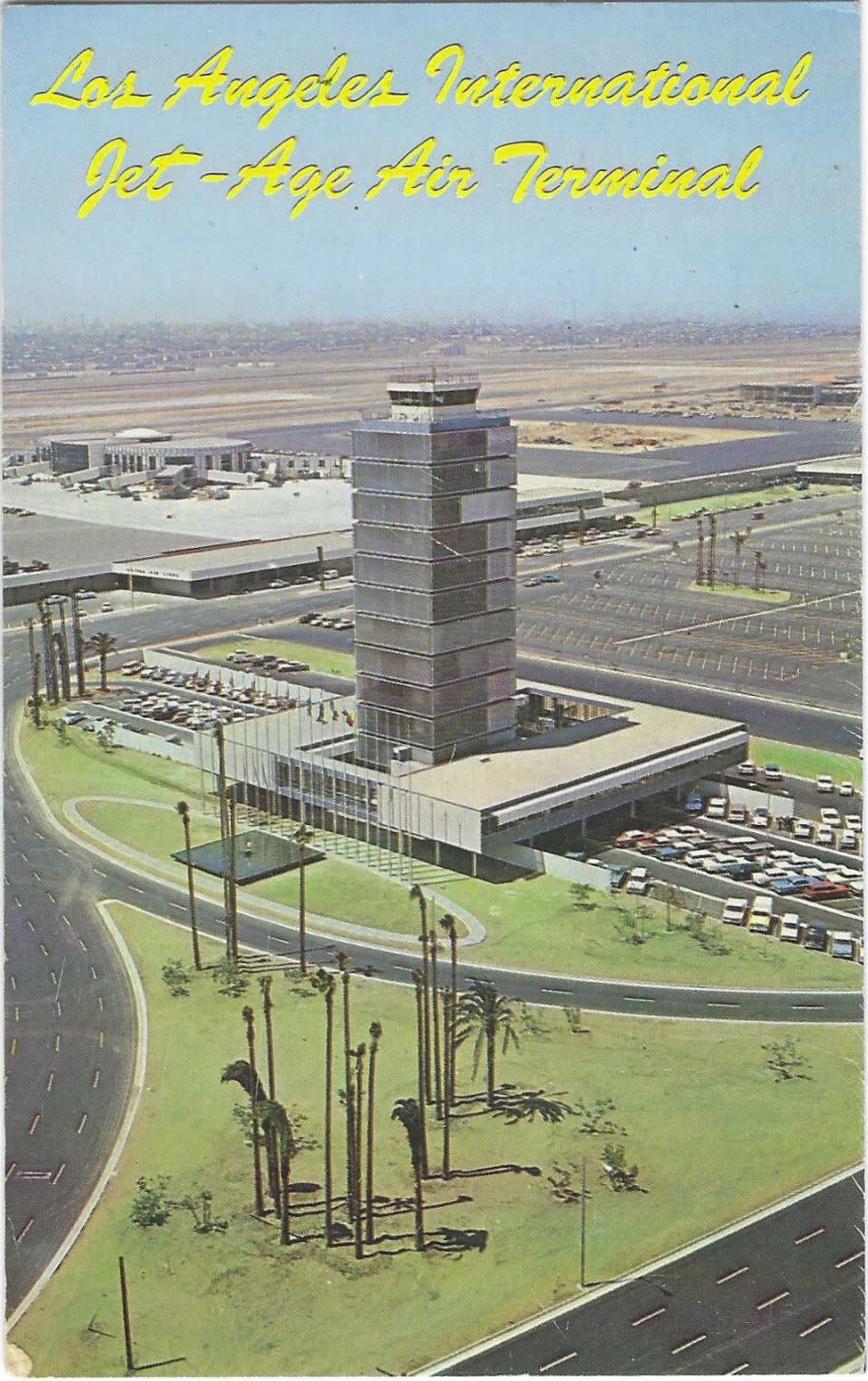

At the other end of that six-mile drive is LAX. Its site in Westchester — a wide, flat stretch along the sea that once yielded handsome harvests of lima beans and barley — was an aviation natural. Just as the January 1910 Dominguez air meet got the fledgling world of flying to look at L.A.’s advantages, the September 1928 air races along the coast, where “every nationally known birdman” was flying, The Times promised, would soon put an “X” on the spot of the future LAX.

The name “Mines Field” was not to honor any heroic aviator, but for William Mines, the real estate man who promoted and then closed the deal, which goes to show you how exalted real estate wheeling and dealing was here — still is.

Mines Field was one of three top contenders for the municipal airport. The other two were far inland, the Bandini site on the east side of the Los Angeles River, and the Vail site, not far away.

The war over the airport site was not as vicious as the 19th century war over where to put the L.A. Harbor. Then, two titanic egos — Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis and railroad baron Henry Huntington — warred through their proxies in Congress, Huntington wanting the harbor in Santa Monica, and Otis in San Pedro.

But it was pretty raw. Mines Field won a City Council airport vote in 1928, but then one councilman began to backpedal, and sore feelings burst forth. Councilman Alber, sarcastically: “This looks to me like the Bandini field is coming to life!” Councilman Shaw, who liked the Bandini site: “Why not?” Councilman Alber. livid: “That swamp!?” By this point the honorable gentlemen had risen abruptly from their seats and had to be gaveled back into them.

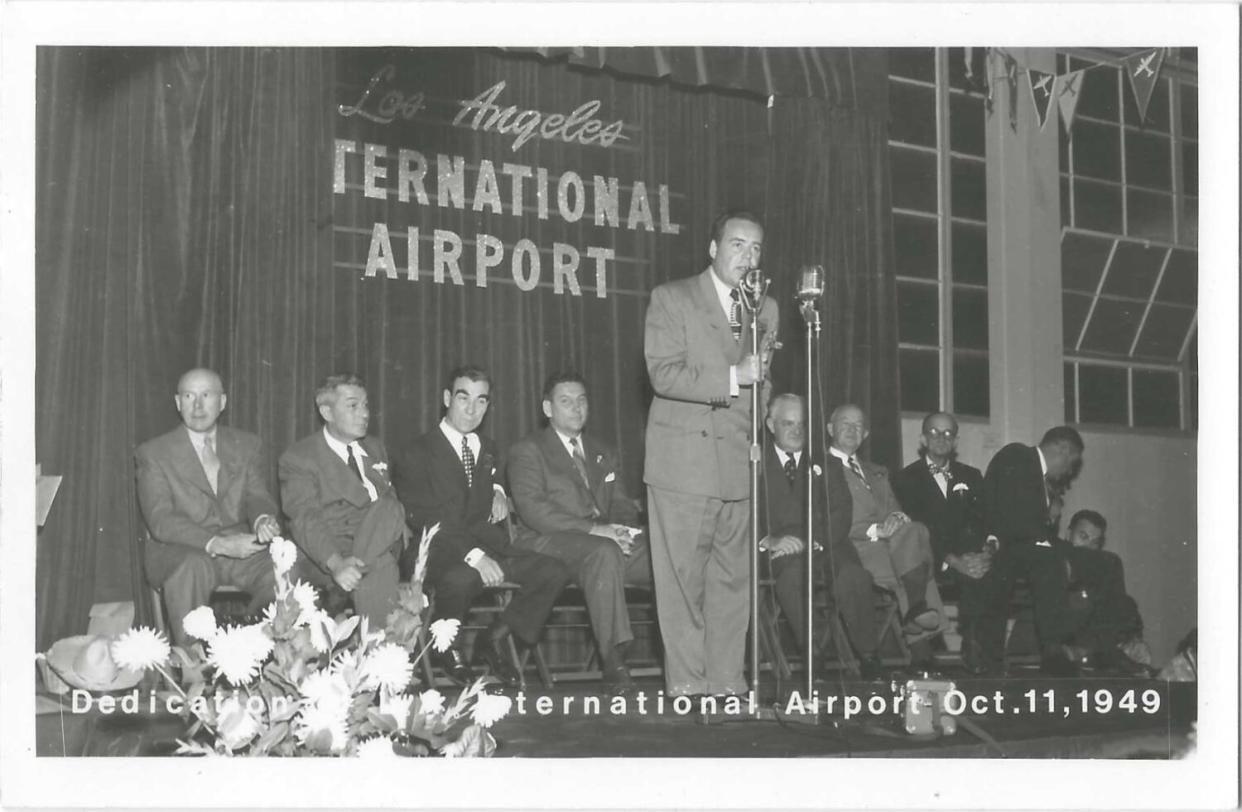

So Mines Field it was, dedicated two years later on land that was first leased and then, in 1937, bought outright. In August 1929, Angelenos swarmed the site to gawk at the Graf Zeppelin dirigible stopping by on its world tour. The war put the kibosh on much in the way of commercial travel, but several airlines opened for business, and passengers took off for the wild blue yonder on Dec. 5, 1946, and the airport took the name Los Angeles International Airport three years later.

As unprepossessing as most of LAX looks, it’s redeemed by the spectacular, late ‘50s-early ‘60s Space Age “theme building.” Unfortunately, it’s a Potemkin come-on. The glamorous restaurant is closed. This is one of L.A’.s most disappointing bait-and-switches. Not being able to keep this glamorous, iconic building going is rather like Parisians shuttering the Eiffel Tower. How about it, L.A.? Even if just for the 2028 Olympics, can we manage the security and commerce logistics long enough to at least make it a visitors’ center, if not a Michelin hotspot?

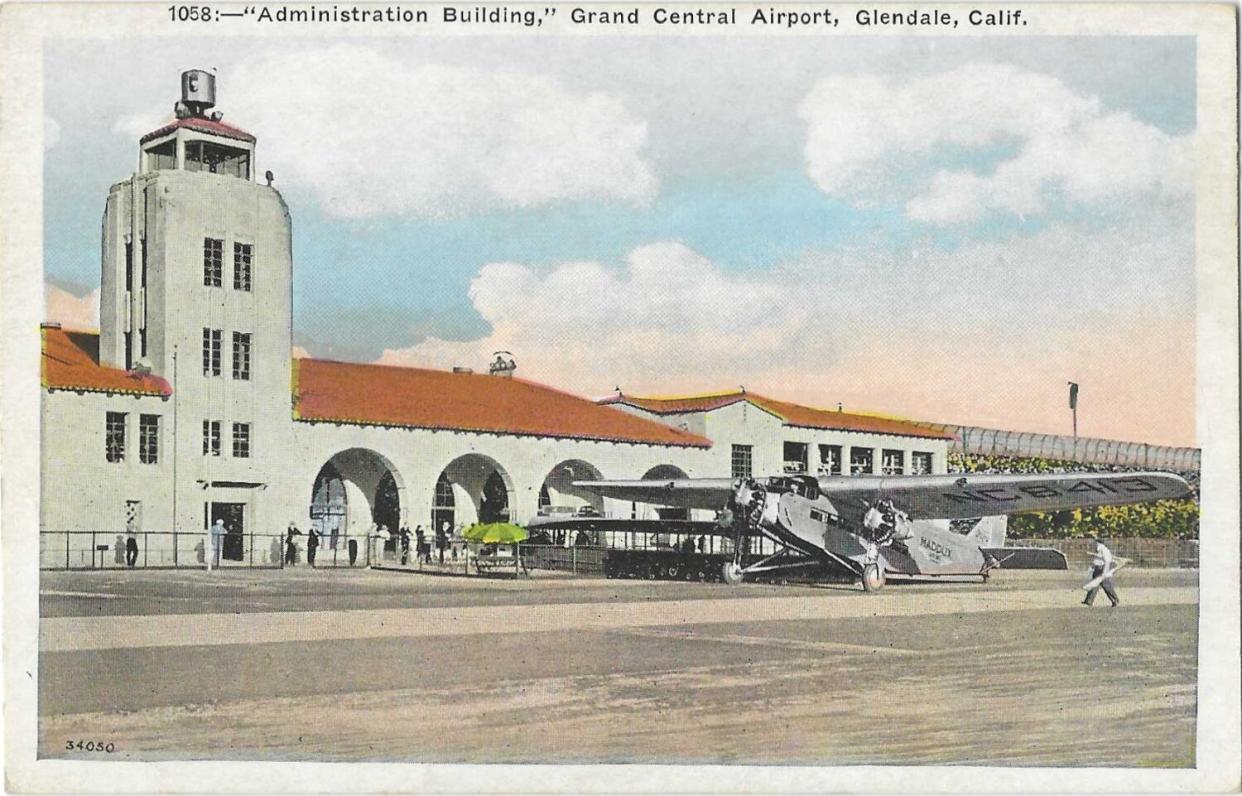

As for those phantom airports, none is more glamorous than Glendale’s Grand Central Air Terminal. From a dirt airstrip a hundred years ago, by 1928 it had the first paved runways west of the Rockies. It was here that publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst kept his plane to shuttle his guests to Hearst Castle.

LAX stole some of its thunder, but it still offered commercial passenger flights until the war put it to military uses, like training pilots for the Royal Air Force. But it couldn’t meet the demands for jet flights, and closed in 1959. The spectacular terminal still stands, on the National Register of Historic Places, and rightly so. Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh flew out of here. And it was here that Howard Hughes, a pilot himself, filmed the dogfight scenes from his World War I epic “Hell’s Angels.”

L.A.’s first airfield was likely in Griffith Park, near the L.A. River. It opened around 1912, and the next year, the renowned aviator Glenn Martin set an altitude record taking off from there. A year after that, the LAPD’s fledgling air patrol pilots were training there. The Air National Guard used the site into the 1930s, and it was a very near thing: Griffith Park, not LAX, was almost the site of the city’s first airport. The City Council was moving in that direction in the 1920s until it was told to back off because an airport would have violated the park’s dedicated purpose. Now, where the old landing strip was, you’ll find the parking lot for the zoo.

Men with money and ambition weren’t waiting for government agencies. They built their own airfields. Movie men found aviation especially glamorous, and even profitable. At the end of World War I, Cecil B. DeMille founded Mercury Aviation, and built a reported three fields: one the short-lived Eaton Altadena airport right alongside the Altadena Country Club, and two in the heart of L.A., one of them at the western edge of today’s Park La Brea apartment complex, and the other a few blocks away on Wilshire, where the gas station sold airplane fuel on one side and gas for cars on the other.

His neighbor was Charlie Chaplin’s older half-brother, Sydney Chaplin, who built Chaplin Airfield around 1919, and like DeMille offered aerial excursions to passengers — among them seaplane flights to Catalina Island. The “airport in the sky” was begun before World War II by the Wrigley family, which owned the island, and now the airport belongs to the island’s conservancy group. Chaplin sold his L.A. airfield to a partner, Emory Rogers, who called it Rogers Field. It soldiered on for another decade or so.

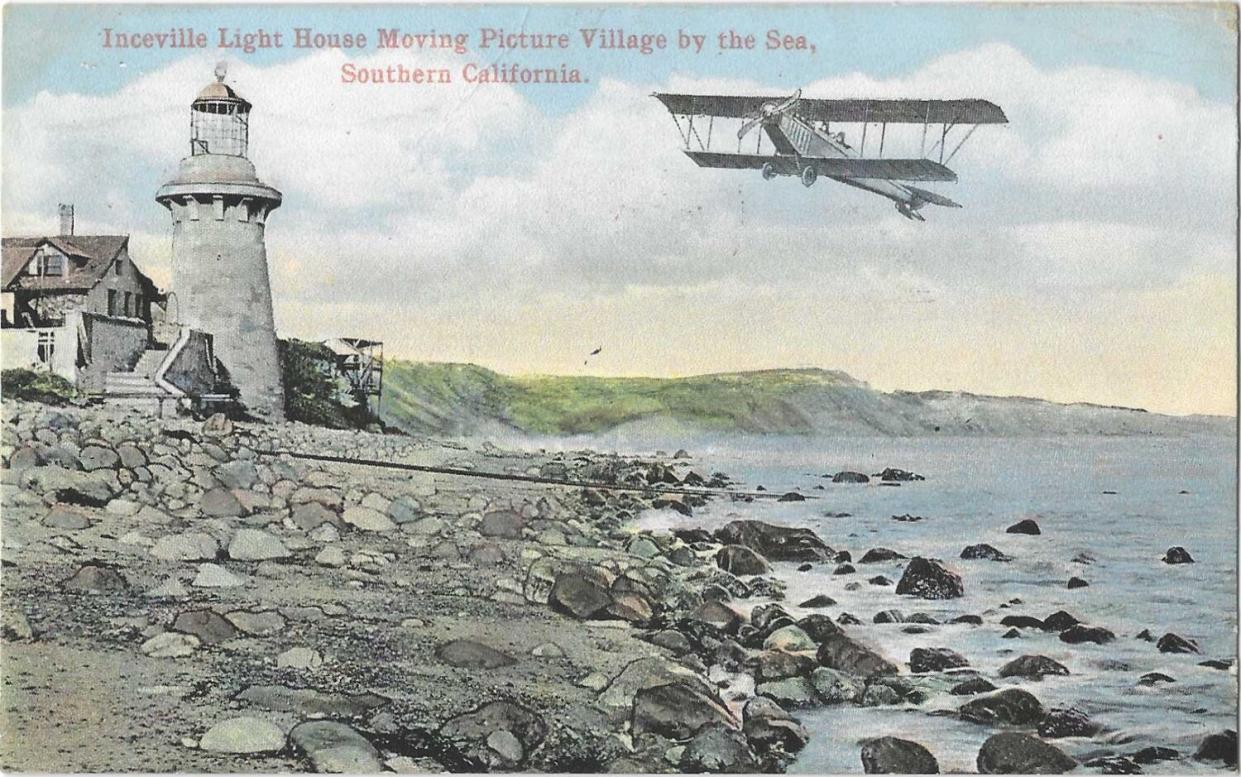

Two years before DeMille even arrived in Hollywood, filmmaker Thomas Ince had established his open-air studio way out yonder in Pacific Palisades. “Inceville” was an enormous piece of property, all photogenic terrain. And in 1914, down the coast a bit he built an airstrip, Aviation Field. Pilots who performed for airshows, and for the movies, operated from there, and one aviator, B.H. DeLay, ran the field for Ince, then bought it in 1920 and renamed it DeLay Field. But not for long; DeLay died in a 1923 air crash that was probably sabotage and remains a mystery.

Here’s another mystery for you: Where were the intense, final airport scenes in “Casablanca” shot?

Not at Van Nuys airport; The Times and others busted that myth a while back. But at a now-demolished hangar just offsite? A Warner Brothers’ sound stage?

I’m not going to referee this one, no siree. But be my guest — go sleuthing.

Here’s looking for you, kid.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.