A famous fellow British author, a Catholic no less, lived in Monaco, twenty miles from Greene’s apartment. Anthony Burgess and Graham Greene knew one another, yet seldom socialized. Still, Burgess remained a faithful acolyte to Greene’s high priest. He applauded Greene’s books in reviews and on TV talk shows and at literary festivals. Burgess dedicated his novel Devil of a State to Greene and delivered a radio lecture celebrating Greene’s seventy-fifth birthday.

Legend has it that their relationship commenced when Greene contacted Burgess in Malaysia, where he then lived, and begged a favor. Greene had ordered some bespoke silk shirts and asked Burgess to deliver them to him in London. One version holds that opium had been sewed into the shirt cuffs and that Burgess knowingly smuggled dope to Greene. Another version claimed Burgess was kept in the dark and had no idea that he was carrying drugs—a capital offense in Malaysia.

Whichever tale is true, Burgess in a sense remained Greene’s bag man. In 1973, he declared, “Let me say at once that The Honorary Consul is as fine a novel as [Greene] has ever written—concise, ironic, acutely observant of contemporary life, funny, shocking, above all compassionate.” Yet this adulation prompted a tart letter from Greene. In a tone un-comfortably familiar to me, Greene challenged Burgess’s journalistic accuracy. “Just to set the record straight about your very generous broadcast; it was not The Heart of the Matter which was condemned by the Holy Office, but The Power and the Glory, and it was The Power and the Glory that Pope Paul VI had read. It does make a good deal of difference because in my opinion The Heart of the Matter would quite rightly be condemned but not The Power and the Glory.”

For all of Greene’s nitpicking about the errors of other writers, he was prone to getting his own published facts wrong. With An Impossible Woman, the book about a colorful, obstreperous doctor on Capri, he was criticized by citizens of the island for committing obvious errors. His daughter, Lucy, had to correct the record when Greene wrote a mistaken description of the ranch in Canada he bought for her.

Eventually, Burgess came to resent what he viewed as Greene’s ingratitude. While Greene had admired Burgess’s early work, his enthusiasm turned lukewarm, then ice cold. Greene wrote to a friend, “I thought Earthly Powers was terrible. [Burgess] writes far too much. Apparently he was wildly indignant that he hadn’t got the Nobel Prize instead of [William] Golding.”

Burgess leveled the charge that Greene was guilty of class prejudices and had never embraced the whole Church body.

Greene told Gore Vidal that he found Burgess’s boisterous self-promotion, particularly his appearances on TV talk shows, distasteful and contemptible. In view of Vidal’s mantra that sex and television were opportunities a writer should never turn down, one wishes Vidal’s reply had been recorded.

Hostilities between the two writers didn’t break into the open until Burgess published an interview that Greene dismissed as absurd. Burgess’s autobiography recounts his side of the controversy:

“I went to Antibes to interview Graham Greene for the Observer. Greene’s apartment was only a hundred yards up the hill from the Antibes station, but I had to take a taxi. Greene, in his middle seventies living with a chic French bourgeoise whose leg was not broken, was fitter than I at sixty-three. We talked and I bought him lunch… when I sent him the typescript of our colloquy [he] accepted that this was a true account. I did not of course use a tape recorder. Later, he contributed to ‘Sayings of the Week’ in the Observer the following remark: ‘Burgess puts words in my mouth which I had to look up in the dictionary.’ This turned me against him. He had long, it seemed, had something against me.”

Burgess speculated that the style and substance of their books had put them at odds. “I had elected the Joycean way in the sense of deliberate hard words (to check the easy passage of the reader, in the manner of potholes on the road) and occasional ambiguity. Greene had made the popular novel of adventure his model. But I felt that the real barrier between us was that between the cradle Catholic and the convert.”

This threw down the gauntlet for a dispute that continued until Greene’s death. In 1988, speaking to the French magazine Lire, Burgess described Greene as an old man of eighty-six who had no friends and who isolated himself in Antibes corresponding on a daily basis with Kim Philby in Moscow. Reiterating his remark about the difference between cradle Catholics and converts, Burgess leveled the charge that Greene was guilty of class prejudices and had never embraced the whole Church body, which in England was dominated by the Irish, along with social outcasts like the Italians.

This was a criticism that had nettled Greene off and on throughout his career. Forty years earlier, George Orwell had accused The Heart of the Matter of theological snobbery and wisecracked that in Greene’s novels, “Hell is a sort of high class night club, entry to which is reserved for Catholics only…He yearns to share the idea, which has been floating around since Baudelaire, that there is something rather distingué in being damned.”

While Orwell appears to have gotten away with his wise-crack, Greene fired back at Burgess: “I know how difficult it is to avoid inaccuracies when one becomes involved in journalism, but as you thought it relevant to attack me because of my age (I don’t see the point) you should have checked your facts. I happen to be 83, not 86, and I hope you will safely reach that age.”

__________________________________

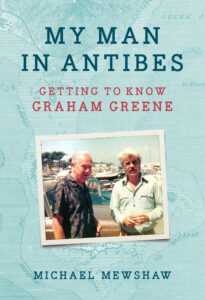

Excerpted from My Man in Antibes: Getting to Know Graham Greene by Michael Mewshaw. Copyright © 2023. Excerpted with the permission of David R. Godine.