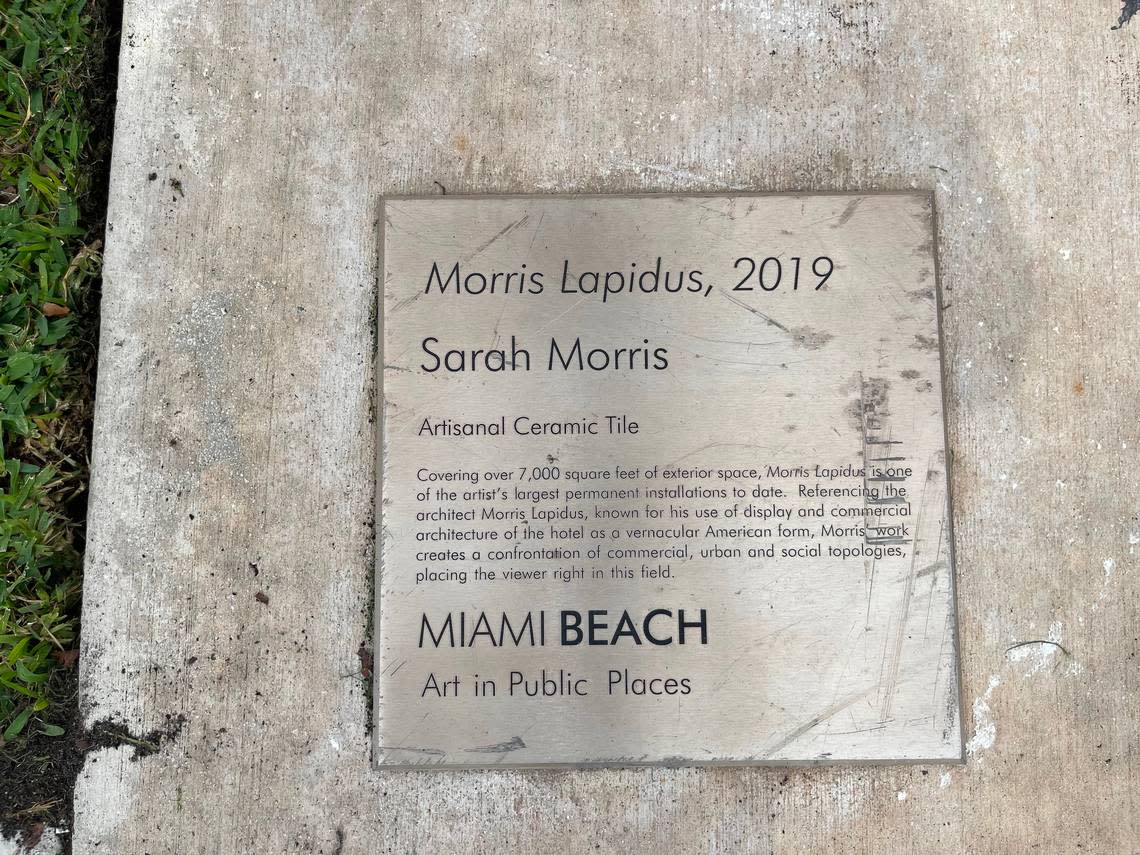

When the City of Miami Beach hired an internationally acclaimed artist to cover the northeast walls of the Miami Beach Convention Center in colorful tiles, it expected a beautiful, permanent public artwork for residents to enjoy.

What it got was cracked tiles, shoddy material and falling debris instead, a lawsuit alleges.

On Friday, the city filed a complaint in Miami-Dade County Circuit Court against artist Sarah Morris and her company Parallax LLC for breach of contract, along with two contracting companies, Home One Contractors Corporation and Moosally Construction, for over $1,000,000 in damages. The city had paid Morris over $1,110,000 to create and install “Morris Lapidus,” an expansive abstract tile artwork, on the north and east facing outside walls of the Miami Beach Convention Center.

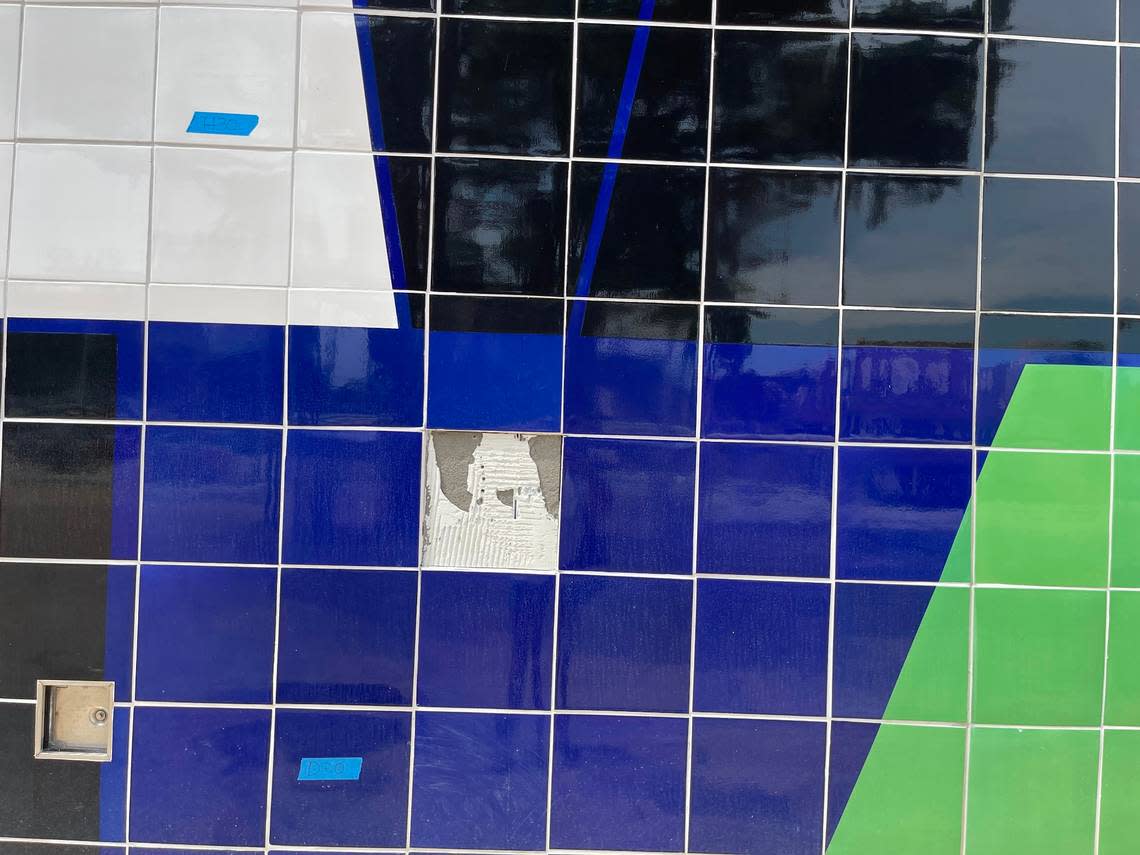

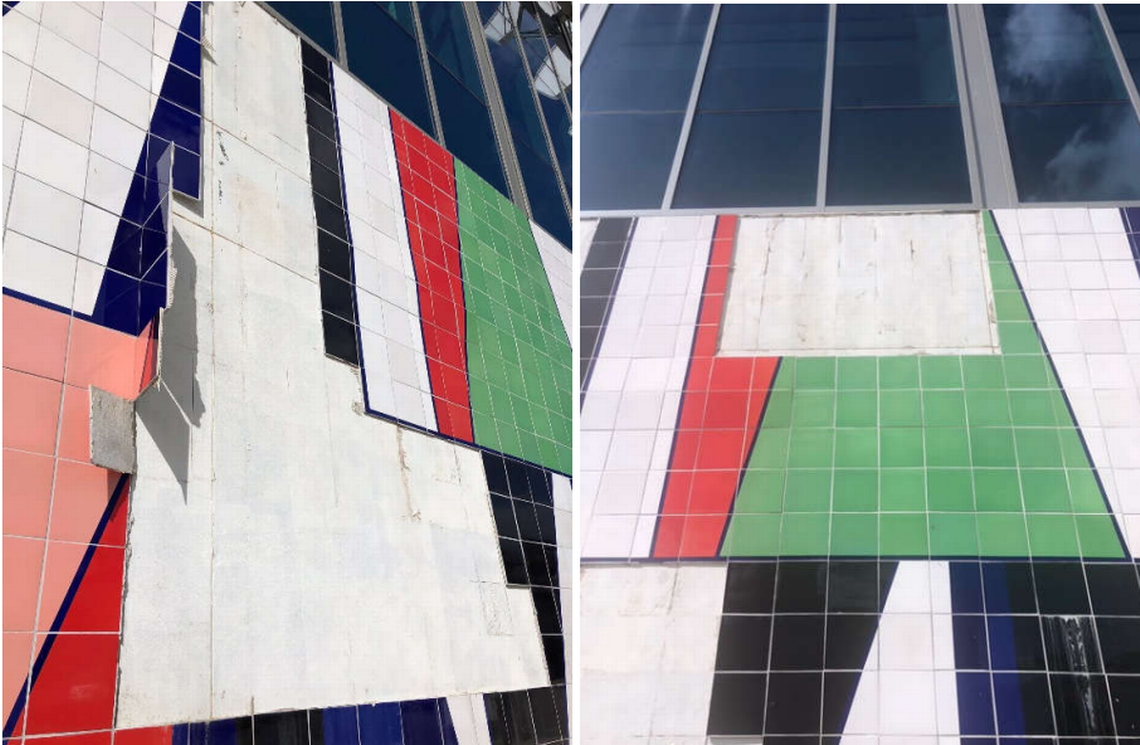

But just months after the work was completed in July 2019, the art became a safety hazard, the complaint said. Tiles were cracking, bulging and falling off the wall. The city eventually installed a protective covering over part of the artwork to prevent tiles from falling onto people.

The city says Morris and the contractors she hired are to blame, adding that she was contractually obligated to repair the artwork if need be, according to court documents. Parallax, though, maintains that the artist was not at fault and that the artwork’s issues stem from when the walls were built.

“Parallax is prepared to vigorously defend itself against any allegations of wrongdoing and looks forward to the resolution of this matter,” the company said through its attorneys, Soto Law Group. “Any damage to the artwork ‘Morris Lapidus’ is a direct result of issues surrounding the design and construction of the Miami Beach Convention Center itself.”

The city’s attorney Michael Kurzman did not respond to a request for comment. Home One declined to comment.

Morris, who is based in New York, is a painter and filmmaker with a long list of international art exhibitions and public artwork installations under her belt. She’s the artist behind the Monaco Reflecting Pools in Key Biscayne, which was installed in 2005. (Her website does not mention the Miami Beach Convention Center project.)

A two year warranty

The saga began October 2016, when the city commissioned Morris to create a site-specific installation at the convention center, which was undergoing a multi-million dollar remodel. The artwork she created was in homage to Morris Lapidus, an architect known for designing Lincoln Road Mall, the Fontainebleau Hotel and the Eden Roc hotel.

“Somehow there was a lightness in [Morris Lapidus’] work because of this treatment of the display or the commercial form, that actually now seems so ahead of his time,” Morris said in a video made by Miami Beach Convention Center. “They are sort of quintessentially American, but you really see it at its core in Miami.”

The installation process itself went through several delays, according to the lawsuit. At one point, the tiles were the wrong size and had to be cut by hand, the city said. The project was completed three months late.

The contract states that Morris is “solely responsible for the quality and timely prosecution, completion and installation of the Artwork and the Project” and for directing and supervising the creation of the tiles, according to court documents. The artist was also responsible for examining the walls to make sure it was OK for the project to move forward, the city said.

“Simply, if MBCC’s walls could not support the Artwork, it was Artist’s contractual duty to notify the City before the Artwork was installed and to design a means of mitigating this issue,” the lawsuit says. “Artist did nothing, leaving the City to believe that the Installation Site was proper and ready for the Artwork.”

Under the agreement, Morris needed approval from the Contract Administrator to hire contractors. And, according to the contract, the artwork had “to be free from defective or inferior materials and workmanship for two years after the date of final written acceptance.” If the artwork needed repairs within that time frame, the artist would fix it at no extra cost to the city, according to the agreement.

The artwork did not last two years.

By Spring 2020, there were already signs of deterioration, the lawsuit alleges, like water damage, cracked tiles, issues with the grout and bulging. In April 2020, the city began contacting Morris about the defects, the lawsuit says.

And then tiles began to detach from the wall. On October 30, 2020, the city said, 29 tiles fell off the east wall portion of the artwork. A few days later, two sections of tiles fell off. Then, another 20 tiles fell off the wall in one day.

Over the course of several months, as the city notified Morris about the artwork’s defects and safety concerns, she hired two firms to investigate the issues, the lawsuit says. The city hired an engineering firm to do its own investigation, which found that the east wall was so problematic, it recommended that the tiles be removed completely.

In several letters to the city, Oscar Soto, Morris’ attorney, identified who he considered the real culprit for the artwork’s damage: the construction companies that built the walls of the convention center. Due to the other companies’ negligence, “the walls were never suitable to receive ceramic tiles” in the first place, Soto said in a Sept. 9, 2021 letter.

“Ms. Morris is an internationally renowned artist, whose site-specific artwork has been installed and displayed in leading cities, such as New York, Paris, Zurich, Basel, Dusseldorf, Frankfurt and Bologna, to say nothing of Miami Beach,” Soto said in the letter. “CMB’s response to the damage to the ‘Morris Lapidus’ installation is an affront to the artist and to Miami Beach’s own standing among the leading cities hosting Ms. Morris’s work. Ms. Morris, the artwork, and the City of Miami Beach deserve better.”

In that same letter, Soto demanded for the city to “promptly disassemble the ‘Morris Lapidus’ installation, as it cannot continue to be displayed in its current condition.”

The artwork still stands.

This story was produced with financial support from The Pérez Family Foundation, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The Miami Herald maintains full editorial control of this work.

Originally published