Tsipora (pronounced Si-Por-a) Prochovnick always starts her work week with a hike — 10 miles and nearly a 5,000-foot climb.

For the Manning Camp wilderness ranger, that’s the only way to get to work.

At 7,920 feet, Manning Camp includes a wooden structure and corrals on a pine-covered flank of Mica Mountain in the Rincon Mountains east of Tucson. It’s the National Park Service backcountry office for summer fieldwork: plant surveys, prescribed fire, trail maintenance and other activities.

“It’s basically a cabin host job,” Prochovnick explained. In April, she got the facilities ready for a Saguaro National Park leadership team meeting. Everyone hiked up, but the Park Service’s pack string of mules brought food and supplies.

People are also reading…

Tsipora Prochovnick is working her second season as Manning Camp wilderness ranger.

“I checked the water system and filled the water trough for the mules,” Prochovnick said.

Maintenance is a key part of the job at Manning, a 118-year-old building built as a private residence in 1905 and supporting federal management agency crews since the 1920s.

The Historic Manning Camp cabin serves as the National Park Service backcountry office for summer field work: plant surveys, prescribed fire, trail maintenance and other activities.

Ranger life

“We usually open the cabin in March and keep it open until November,” Prochovnick said. Due to heavier snow this year, the opening was late March. Her seasonal appointment runs March through November, with eight 10-hour work days and six days off. Days 1 and 7 include the hike up or down to Manning; Day 8 is an office day. This is her second year on the job.

“I love how diverse the job is,” she said. “You get up there and you have seven options of what you want to do today. But you have be self-directed.”

Prochovnick arrived at Manning on May 15 to find that one of two refrigerators powered by propane had gone out, leaving a whole fridge full of rotten food.

“I have plenty of food,” Prochovnik said, “but I was disappointed about the (formerly frozen) chickens.”

She also interacts with visitors and checks permits. Manning Camp has an adjacent campground for hikers — with reservations required on the government recreation.gov site (see tucne.ws/1ng7). But it’s a small part of the job.

Despite a prime location in cool ponderosa pine, “we don’t get that many visitors,” she said. It’s a long hike up the mountain, and “no matter how early you start, it’s pretty hot in the summer.”

The Park Service takes a fairly direct route to Manning through the moth-balled Madrona Ranger Station on the east side of the Rincons. This requires crossing private land closed to the public, but the Park Service has access. (The X-9 Ranch owner closed the area in 1967, and the closure remained after the land was sold and subdivided for private homes.)

With five camping areas (Juniper Basin, Grass Shack, Happy Valley, Spud Rock Spring and Manning) and a large trail system, the Saguaro Wilderness Area offers many loop trips for backpackers but almost all routes start around 3,000 feet, so the first 5 miles are hot in the summer.

Trailhead distances to Manning: from Douglas Spring (end of Speedway) — 12 miles; Loma Alta — 13.7; Italian Springs —12; Tanque Verde ridge (Javelina Picnic Area) – 16. The shortest hike from the far side of the mountain (1.5-hour drive from Tucson) is Turkey Creek Trail, about 9 miles. The Arizona Trail joins Manning Camp Trail; from the park boundary, it’s 13.5 miles to Manning.

“By far the biggest use of Rincon high country is the Arizona Trail thru-hikers usually in late March and April and then again in October-November,” Prochovnick said. “I see probably 20 a day during the season.”

Most don’t camp at Manning because the reserved six-site campground does not work well for thru-hikers. It allows six people per site. Since most thru-hikers plan and hike alone, this means six single hikers might reserve the whole campground. The Park Service is looking at an adjacent site that might be set up for single-hiker sites with permits still obtained through recreation.gov.

Recently, the Manning area was decked out with tents: for five biological technicians, a Saguaro Trail Crew member and three packers who came with two “pack strings” (mules for hauling supplies). Sid Kahla, a rancher from Sierra Vista, has packed for the Park Service since 2009. He rode one of his horses and led his four mules; the other seven mules belong to the park and were wrangled by two Park Service employee packers. Field crews buy their own food and supplies brought up by the mules. Manning has a few big on-site tents, but most field people have their own.

Contractor Sid Kahla packs up mules for a 10-mile morning haul down from Manning Camp to the Madrona trail head.

The pack train also brought propane fuel and mule feed. The big May project was moving a camp for the Saguaro Trail Crew. The winter crew was based at Grass Shack, working on the Manning Camp Trail. The summer trail crew will have a “spike camp” on Heartbreak Ridge between Manning Camp and Happy Valley Saddle. Tents, food, water, tools and fuel will be packed in. The pack string will spend a night at Manning, a day packing supplies to the spike camp and then another night at Manning, requiring a lot of pellets for the mules.

The evolution of Manning Camp

Manning Camp, circa 1906-1907, was a hub of activity.

Manning Camp was built as a private summer home. Levi Manning, who came to Tucson from the South in 1884, worked as a reporter and later was Tucson mayor. In 1904, he homesteaded 160 acres in the Rincons; he built the Manning Cabin and a 12-mile wagon road in 1905. The cabin included a fireplace, kitchen, bedrooms and a piano.

The land became Coronado National Forest in 1907, and the cabin fell into disrepair until 1922, when the Forest Service reconditioned it to house fire and trail crews. In 1935, most of the Rincons were transferred to the Park Service as Saguaro National Monument, now Saguaro National Park. In 1975, the cabin was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In 1976, much of Saguaro Park was designated wilderness.

The camp water supply is a spring developed by the Manning family and excavated by the Park Service into a large pond. Below that, a tinaja (water pocket) drops into a large pool. A nearby pumphouse powered by a small solar panel filters the water, which is pumped to a large tank on the hill. It’s then gravity flow for water to the cabin.

The “cabin” is actually two structures connected with a covered walkway. The central part decayed many decades ago and was removed. One structure contains a propane stove, refrigerators, a large table and supply closets. The other is a toolshed. The breezeway was filled with stock bridles, saddles, harnesses and feed; some backpacks and tools were hung on hooks.

The propane stove was not working too well, so Prochovnick suggested cooking outside either on a large open stove or a big campfire. (She got the stove fixed later in the week). She showed the technicians new to Manning what worked and what did not work in the kitchen. She displayed a whiteboard where she said she’d post names of people assigned to three chores: wash dishes, wipe down all surfaces and sweep. “This year we are winning the battle with mice.”

“Some bats moved in last year,” she said. “I had to go down to the park and get a high frequency rodent repellant to encourage them to move out. They would screech at me when I worked on the tools.”

Trail crew member Kristian Sliwa was helping Prochovnick for the week. He had an overlap between the park winter trail crew and the summer crew coming on the next week. Prochovnick planned to clean out organic matter from the water source, clear logs from trails around Mica Mountain, deep clean the cabin and sort, clean and inventory tools. “Some jobs, like moving a log, are better with two people,” Prochovnick said.

The park fire crew recently camped at Manning while preparing for a prescribed fire. Since they can use chainsaws, Prochovnick enlisted them to buck up firewood for the cabin. Since the area is wilderness, trail crew members use non-mechanized tools: crosscut, smaller saws and hatchets.

Park Service employee Kristian Sliwa watches Tsipora Prochovnick use a small saw for fine cut to finish cutting out log on Bonita Trail in Saguaro Wilderness.

Tristan Blue will start in June as the second wilderness ranger. Prochovnick and Blue will alternate at Manning Camp but overlap one day. “Last year we had no overlap and both of us (rangers) were new,” Prochovnick said. “It took awhile to figure out what needed to be done.”

A San Francisco native, Prochovnick got an art degree but fell for wilderness work during a summer trail crew stint in Kings Canyon Wilderness with the California Conservation Corps. She has worked as a wilderness ranger or trail crew member on national forests and parks in Montana, Wyoming and California. “I worked on the Saguaro Trail Crew off and on since 2012.”

Photos: Saguaro National Park through the years

Saguaro National Park

The Saguaro National Monument cactus garden in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

The Saguaro National Monument West visitors center, left, with two rangers’ apartments under construction in 1966.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Monument East unit loop drive in 1958.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Monument East, ca 1950s.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Monument in 1935.

Saguaro National Park

Snow at Saguaro National Park East (then called Saguaro National Monument) on Dec. 23, 1965.

Saguaro National Park

Undated photo (probably 1950s) of tourists enjoying picnics and hiking at Saguaro National Monument.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Monument visitors center ca 1940s.

Saguaro National Park

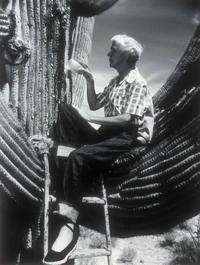

Home Shantz, a plant scientist and president of the University of Arizona in the 1920s, was instrumental in establishing Saguaro National Monument in 1933.

Saguaro National Park

Panorama of cactus forest in Saguaro National Monument, 1931.

Saguaro National Park

Dr. Alice Boyle applies Penicillin to a Saguaro cactus at Saguaro National Monument. Dr. Boyle’s studies of saguaros included treatments with penicillin that were somewhat successful. Later research showed that the loss of old saguaros was a result of age and periodic freezes, not a “blight”!

Saguaro National Park

The Freeman family in Saguaro National Monument in 1936.

Saguaro National Park

Freeman’s adobe home in Saguaro National Monument in 1934.

Saguaro National Park

A park ranger with visitors on the loop drive in Saguaro National Monument in 1961.

Saguaro National Park

Centennial Saguaro cactus outside the Saguaro National Monument visitors center.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Monument cactus

Saguaro National Park

Snow storm in Saguaro National Monument in 1937.

Saguaro National Park

A view looking south from Signal hill at the Tucson Mountain Range in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

A view looking east from Saguaro National Park, along Picture Rocks Road in the Tucson Mountain District in August, 2016. In the distance, cloud rise over the Santa Catalina Mountains.

Saguaro National Park

A Saguaro carcass framed at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

A southerly view out the window of a picnic shelter built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s that was built with surrounding rock in the Ez-Kim-In-Zin Picnic Area at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

A desert tortoise makes its way down Kinney Rd. in the Saguaro National Park West, Wednesday, August 10, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

A Saguaro cactus off Golden Gate Rd. holds a top full of flower buds at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

A view looking south from Signal hill towards Wasson and Amole Peaks from left in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District in August, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Visitors take a look at trail maps on the patio of the Red Hill Visitor Center at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Visitors from Denver stroll one of the many trails off Golden Gate Rd. at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Panoramic view from Spud Rock, including the city of Tucson, from six images, ranging from southeast at left to northeast at right, near Mica Mountain on the western slopes of the Rincon Mountains in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

A hawk watches from his perch at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

A zebra-tailed lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) perches on a rock near the Signal Hill Picnic Area at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Panther and Safford Peaks in the Tucson Mountains North of Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Stella Tucker uses the sharp edge of a stem of a Saguaro fruit to slice the husk to get to the sweet meat inside as she harvests the fruit in the Saguaro National Park in 2005.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Stella Tucker uses a kuipaD to harvest saguaro fruit in the Saguaro National Park 2005. During the early summer Tucker camps out in the park to harvest and cook the fruit just as her Tohono O’odham ancestors did. Tucker died in 2019 at age 71.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Bob Martens uses a kuipaD, lengths of Saguaro ribs topped by a small limb of creosote, to knock down ripe Saguaro cactus fruit as he helps Stella Tucker during the Tohono O’Odham harvest at Saguaro National Park in 2005.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Under the early morning sun, Jerry Yellowhair strengthens the joint where a small creosote branch is attached to a length of Saguaro rib to make a kuipaD, used to reach the Saguaro fruit.

Saguaro National Park

1907: Prominent Tucsonan Levi Manning and his family spent the summer at a get-away log cabin high in the Rincon Mountains.

Saguaro National Park

Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park East, in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Some of the pots, pans and iron skillets used by the staff during their stays at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Next generation ranger Ryan Summers, left, and wilderness ranger Shannon McCloskey look over the camps visitors log shortly after arriving at Manning Camp 8,000 feet above sea level in the Saguaro National Park, on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Horse shoes on one of the logs making a wall in the cabin at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Next generation ranger Ryan Summers splits wood for the evening’s fire at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

The view east over Reef Rock, lower left, from Rincon Mountains near Manning Camp in Saguaro National Park, June 2, 2016

Saguaro National Park

Wilderness ranger Shannon McCloskey, left, and next generation ranger Ryan Summers prepare to do some upgrades to the facilites at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Sid Kahla, left, and Thor Peterson get a pannier balanced on Goose while packing seven mules for a resupply of Manning Camp ranger station in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Park trails supervisor Nick Huck, left, and chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis split up a box of paper towels, distributing the weight evenly among the panniers while preparing for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp on April 14, 2016. Seven mules were in the supply train and each mule can carry between 100 and 120 pounds.

Saguaro National Park

Wasson and Amole Peaks at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Monsoon clouds gather over the cactus forest in the Saguaro National Park West, Wednesday, August 10, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro cacti backlit by western sun at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

A horizontal sliver of sun catches a stretch of cactus in front of the Rincon Mountains just off the Mica View Trail in Saguaro National Park East, Friday, August 12, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

This old stone building was constructed in the 1930’s by the Civilian Conservation Corps at the Cam-Boh Picnic Area at Saguaro National Park West.

Saguaro National Park

In the aftermath of an evening summer storm, lightning arcs through the night skies over the Saguaro National Park West in 2012.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Park trails supervisor Nick Huck, left, and chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis split up a box of paper towels, distributing the weight evenly among the panniers while preparing for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp on April 14, 2016. Seven mules were in the supply train and each mule can carry between 100 and 120 pounds.

Saguaro National Park

A Harris’ antelope squirrel, a year-round resident of the Sonoran Desert, comes out of from under a bush for a look-see near the Golden Gate Road at the Tucson Mountain District of the Saguaro National Park in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

A jack rabbit munches on some greens near the Broadway Trial Head at Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Hikers in Saguaro National Park, like these on the King Canyon Trail in the park’s unit west of Tucson, can pay park entrance fees at trailheads using a smartphone.

Saguaro National Park

Loop of connected trails at Saguaro National Park East, made up Shantz, Pink Hill, Loma Verde, Cholla and Cactus Forest trails in 2012.

Saguaro National Park

From atop an outcropping under the Rincon Mountains, Next Generation Ranger Ryan Summers points out the ancient fault line that shifted and formed the Tucson valley to a group of visitors during a geology tour of Saguaro National Park East on April 26, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaros stand on a ridge line as massive storm clouds drift in the distance along the Hohokam Road at the Tucson Mountain District of the Saguaro National Park in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis gets the strap as tight as possible with the help of trail supervisor Nick Huck while preparing a 70+pound propane tank for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park, Rincon District on April 14, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Park ─ Sunset can be a colorful time along a network of trails near the eastern end of Broadway.

Saguaro National Park

Ranger Donna Gill points out cactus flowers and birds during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Hedgehog cacti are in brilliant fuchsia bloom at many sites around Tucson from Sabino Canyon to Tucson Mountain Park and Saguaro National Park in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Russell Jones takes a picture at the Saguaro National Park West Red Hills Visitor Center in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Poppies were blooming profusely at Saguaro National Park West on February 23, 2015

Saguaro National Park

Mike Ward of Saguaro National Park, left, and volunteer LaDeana Jeane observe a Saguaro cactus while conducting a census at the east section of Saguaro National Park in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Gavin Youngstrum drives a roller along the bed of the new Mica Springs Trail, work which will make it ADA compliant in Saguaro National Park East on April 22, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Power tools and motorized equipment is used very rarely in the park. The trail is not in a wilderness area so the prohibition on the use of power tools and machinery doesn’t apply.

Saguaro National Park

A blue Arizona lupine mixed in with a handful of yellow bladderpod along the Ringtail Trail in Saguaro National Park Tucson Mountain District in 2013.

Saguaro National Park

Park Ranger Ann Gonzalez watches the campers in her group as they go over a map during Junior Ranger Wilderness Day Camp at the Saguaro National Park in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Petroglyphs are among the many wonders at Saguaro National Park West.

Saguaro National Park

Runners top the first climb as the sun rises at 6:30am, during the annual 8K Saguaro National Park Labor Day Run at Saguaro National Park East in 2007.

Saguaro National Park

A saguaro under the stars, including a smudge of the Milky Way, at the Broadway Trail Head at Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Sunset reflected in a mud puddle left over from heavy rains a few days earlier at the Broadway Trail Head of the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

The moon hangs high over Wasson Peak as Ranger Donna Gill leads hikers during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Volunteers help yank out the nonnative, invasive buffelgrass at Saguaro National Park East.

Saguaro National Park

Using a laser, amateur astronomer Joe Statkevicus points out a few interesting objects in the night sky to Landon George and Vickie Miller at a Saguaro National Park East Star Party in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

A bee works through a patch of baldderpod in the Saguaro National Park Tucson Mountain District along the Ringtail Trail in 2013.

Saguaro National Park

Trail worker Brad Duffe redistributes material as he and his trail crew lay down a bed for a new surface, part of remodeling the Mica Springs Trail to make it ADA compliant in Saguaro National Park East on April 22, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Riders maneuver their mounts down a hillside just north of the Douglas Spring Trail in the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District, Friday Nov. 27, 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Tim and Connie Phillips, from Salt Lake City, look for photo angles during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016. The retired couple sold their home and are “following the weather” across the country in their RV.

Saguaro National Park

A few items, photos and brief entries in tiny notebooks from an unofficial shrine at Mica Mountain in Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

The sun sets over the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District on Oct. 8, 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Scarlett Gates and the rest of the tour group watch the last few minutes of daylight from a rock outcropping along the Tanque Verde Ridge Trail during their guided sunset hike in Saguaro National Park East on April 16, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Gold poppies stand out against a backdrop of cacti and blue desert sky at Saguaro National Park west of Tucson on March 11, 2019.

Saguaro National Park

Rainbows pop up over Saguaro National Park East, as the first major monsoon storm of the season begins to roll into the valley, Tucson, Ariz., July 11, 2020.

Saguaro National Park

A half rainbow arcs over Saguaro National Park East as a highly localized cell of monsoon rain sweeps through a small band of the eastern valley, Tucson, Ariz., July 28, 2020.

Saguaro National Park

A light coating of snow remains on the Rincon Mountains seen nearby the Broadway Trailhead in Saguaro National Park in Tucson, Ariz. on January 27, 2021.

Saguaro National Park

A cactus in the Saguaro National Park East stands in front f the snow in the higher reaches of the Santa Catalinas, Tucson, Ariz., March 13, 2021.

Saguaro National Park

A lighting strikes hits in the Saguaro National Park, east of Tucson, Ariz., July 29, 2021, one of several storm cells that skirted the city.

Saguaro National Park, east and west, shows some of the best of Southern Arizona.