“It was something we’d seen before,” is how Martin Scorsese described the earliest drafts of his new film, Killers of the Flower Moon, in an interview with Deadline just after the Cannes premiere. The film is based on a book of the same name, by David Grann, which tells the true story of a series of horrifying murders in 1920s Oklahoma. Most of the victims were members of the Osage tribe, with deaths orchestrated in order to lay claim to the oil-rich land that the tribe held legal claim to. The book focuses on the investigation into the murders, successfully led by Tom White, who was working for the federal agency that would become the FBI. The problem the filmmakers encountered was that White wasn’t dramatically interesting, and centering him turned the story into a “savior” narrative. Scorsese was correct when he said this type of story had been seen before. The FBI Story, a little-remembered James Stewart movie from 1959, also tells the story of the Osage murders, from the perspective of the FBI.

What Is the True Story Behind ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’?

The script for Killers of the Flower Moon was eventually rewritten to feature the marriage of Ernest and Mollie Burkhart. Ernest was the nephew and accomplice of William Hale (played by Robert De Niro in the film), who conspired against the Osage people. Mollie was his wife, and many of the victims were members of her immediate family. They’re played in the film by Lily Gladstone, in a breakout role, and Leonardo DiCaprio, who’s starred in five Scorsese movies before this one. DiCaprio was originally going to play White, but after the rewrite shifted the focus to Ernest, he took that role instead, and the role of White went to Jesse Plemons.

Here’s the odd thing: after this casting shuffle was announced in 2021, many outlets assumed that Plemons had taken over as the star of the film, while DiCaprio “had segued to a secondary lead.” This wasn’t what one might expect given the relative fame of the two actors (both of whom are excellent in general). But not only that, it ran contrary to the filmmakers’ public statements. Screenwriter Eric Roth straightforwardly told Collider that Tom White was not the solo lead of the film, but this failed to dispel the rumors. That the presumption continued — right up until the recent release of the film’s extremely DiCaprio-heavy trailer — says a lot about how predisposed the modern audience is to expect that a crime story will center on a law enforcement protagonist.

‘The FBI Story’ Paints Cops in a Very Flattering Light

The word “copaganda” was coined to describe the vast portion of our culture’s storytelling that’s dedicated to portraying police work as heroic. The sheer mass of this body of work, theoretically at least, has a psychological effect, conditioning people to believe that most law enforcement officers are as decent and hyper-competent as their fictional portrayals usually are (recent years have made it pretty clear that this isn’t the case). There’s some controversy over how broad we should be in defining things as copaganda, with some stepping up to defend work they admire from this pejorative label. Think HBO’s The Wire. It presents many individual police officers as heroic while critiquing the system that thwarts their desire to do meaningful work. Debates over whether The Wire is copaganda can become pretty intense.

If that controversy bothers you, well, don’t worry about it. Because no one would be willing to make the same arguments on behalf of The FBI Story. In fact, if you had told Mervyn LeRoy, the film’s director, that he had directed a propaganda film for the FBI, he’d have thanked you for the compliment. As he wrote about the film in his career-spanning memoir, his intention was always to “bring credit to the FBI.” Not only that, but J. Edgar Hoover, the historical super-villain who served as FBI director for nearly 40 years, (according to LeRoy, “a close personal friend”), essentially had the final cut over the movie, in exchange for allowing the production to film in FBI headquarters and for providing technical advice. Two agents were on set every day. The FBI had approval over the crew, and at one point, demanded that a scene be re-shot because, for reasons that were never explained, they didn’t approve of one of the extras.

The James Stewart Movie Tells the Story of the FBI’s Greatest Hits

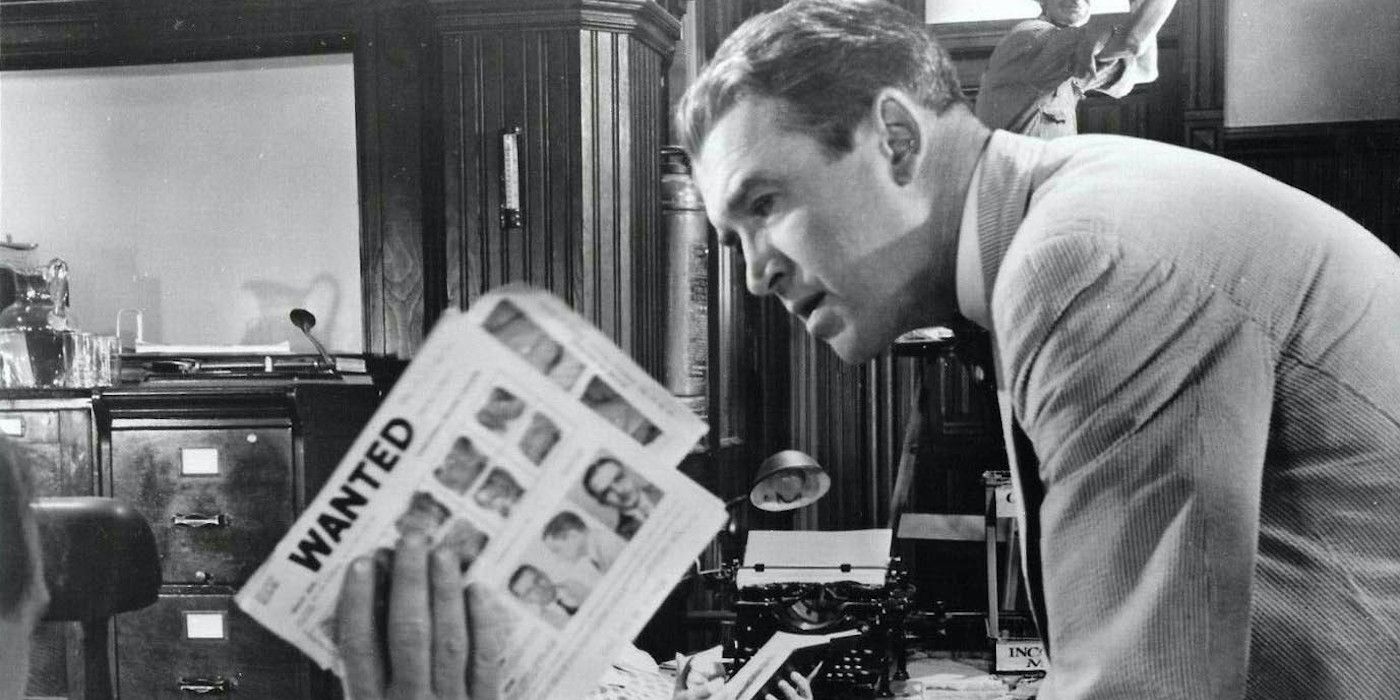

The FBI Story depicts several real cases investigated by the FBI, over a span of decades. James Stewart plays “Chip” Hardesty, a fictional character, who, in the film, happened to always be at the center of things. The tense opening sequence, probably the best of the film, is a fictional account of a murder, and the murderer’s eventual apprehension as a result of the FBI’s cutting-edge investigative techniques. This sequence is narrated by Stewart and is eventually revealed to be part of a lecture he’s delivering on his lifetime of experience.

The movie quickly establishes its intentions. Not only does it mean to present the FBI as a highly advanced machine of justice, but it specifically wants to present J. Edgar Hoover as the man responsible for building it. Hoover plays himself in the film, briefly, and is otherwise played by stand-ins, seen only as an out-of-focus shoulder, or a shadow. His role in this film is a lot like Michael Jordan’s in the recent film Air. The film sees Hoover as a historical figure so transcendent that no performance could do him justice.

After this prologue, Hardesty’s story begins. He’s a young agent working for the FBI in its infancy. Before Hoover’s arrival, it’s a bureaucratic backwater defined by “politics and laziness,” somewhat like The Wire‘s Baltimore police department. Hardesty, an idealist frustrated by the bureau’s dysfunction, promises his fiancé (Vera Miles), that he’ll resign and become a lawyer. But after their wedding, Hoover takes over the Bureau, and Hardesty is entranced by his vision of building the most professional law enforcement agency in the world. As Hardesty’s narration describes it, “lawyers, accountants, scientists, all working together.”

‘The FBI Story’ Is Uninterested in the Humanity of the Osage People

The Osage murders were one of the earliest homicide investigations conducted by the FBI, and that story occupies 15 minutes early in the movie. It follows a brief but bizarre interlude where Hardesty investigates the Ku Klux Klan, a sequence that, believe it or not, never explicitly acknowledges the Klan’s racism, or mentions the existence of Black people.

So it should perhaps not be surprising that its depiction of Osage people is dehumanizing. The victims of the killings were largely wealthy, as every member of the Osage Nation was entitled to a percentage of the money generated by the oil that had been discovered on the Osage Reservation. The film doesn’t have any speaking roles for any Osage people, only depicting them as comical figures who don’t know what to do with their riches, spending it on junk. The stereotypical music that plays over these tableaus is a clear sign that the film is mired in bigotry, even if its villains are bigots.

Through undercover work, surveillance, and forensics, Hardesty and his team eventually close in on the killers, who are rough approximations of the uncle and nephew played by DiCaprio and Robert De Niro in Scorsese’s film. (The victims are named accurately, the killers have their names changed.) The nephew stands to inherit a lot, as he’s married to the sister of two of the victims. This mirrors the story of Ernest and Mollie Burkhart. This movie’s version of Lily Gladstone’s character is also named Mollie, but she’s only alluded to and never appears onscreen.

The film has little interest in the nephew either, here named Albert and played by Paul Smith. And yet, Smith’s few appearances provide validation for Scorsese’s decision to refocus the story around this character and his marriage. Whenever he’s on the screen, Albert is the most interesting character: in over his head, terrified, and desperate for a way out. Smith always has far more complex emotions to play than the bigger stars he’s supporting, and often steals the screen from them, despite the general ambivalence of the camera to his existence. You wish you could see more of him, perhaps follow him home.

Why Should We Care About the Home Lives of FBI Agents?

But, Albert is not the character we follow home. The sequence ends abruptly, as Hardesty learns that his wife has suffered a miscarriage. This family tragedy escalates the central tension of the film, the strain that Hardesty’s job puts on his marriage. His wife has difficulty forgiving him for breaking his promise to quit the FBI, and later, for their son’s decision to follow in his father’s footsteps by enlisting to fight in World War II. It’s a familiar and unfortunate “nagging wife” role, and scenes of family strife take up an astonishing amount of this movie’s runtime.

Criticism of copaganda tends to concern itself with overly aggrandizing depictions of police work. But it’s also worth noticing how much time we’re forced to spend thinking about the fictional romantic partners of law enforcement officers. These storylines are often contrived and boring (and rarely confront the higher rates of domestic abuse in law enforcement families). And they’re just as likely to have a psychological conditioning effect in their omnipresence.

The real Agent Tom White does appear to have been a well-intentioned and competent officer of the law, and he was honored for his work by the Osage people. But that doesn’t mean he’s a character fit to be at the center of a large-scale movie. Killers of the Flower Moon won’t be the first film to center on the lives of criminals or the victims of crime, and may not go far enough in centering the Indigenous community, whose story this is. But in its high-profile refocusing away from law enforcement, it has a chance to break a familiar spell.