We interviewed ten URiM alumni from a Dutch medical school to learn more about their role models during medical school. The results of our analysis are presented below in three themes (role model definitions, identified role models and role model functions).

Role model definitions

In the definitions of role models, the three most recurring elements were: social comparison (the process of finding similarities between a person and their role model), admiration (looking up to someone) and emulation (wanting to copy or obtain certain behaviours or skills). Below is a quote that contains the elements admiration and emulation.

“The person you look up to, the one that makes you think that’s who I want to be like.” [R4].

Second, we found that all participants described the subjective and dynamic aspects of role models. These aspects describe how people do not have one fixed role model, but how different people have different role models at different times. Below is a quote in which a participant describes how role models change along with a person’s own personal development.

“When your own norms and values change, you can also get another role model, I suppose.” [R7].

Identified role models

Hesitance towards role models

None of the alumni could come up with a role model right away. In analysing answers to the question ‘Who is your role model’, we found three reasons why they found naming a role model difficult. The first reason, that most of them gave, was they had never thought about who their role model was.

“Before this interview I had never thought in terms of role models.” [R9].

The second reason that participants gave was that the word ‘role model’ did not fit their perception of the people around them. Several alumni explained how role model is too grand a label to give to anyone, because nobody is perfect.

“I think it’s something very American, that it’s greater, like ‘That’s the guy I want to be. I want to be Bill Gates, I want to be Steve Jobs’. […] So, I don’t really have one role model in a bombastic way like that, honestly.” [R3].

“I remember several people from my internships that I wanted to be like, but that’s not like saying: this is a role model.” [R7].

The third reason was that participants described having role models as a subconscious process, as opposed to an intentional or deliberate choice that they could easily reflect on.

“I think it’s something you deal with subconsciously. It’s not like saying: ‘that’s my role model, that’s the way I want to be’, but I do think that subconsciously you’re affected by others who have been successful.” [R3].

The participants were noticeably more comfortable discussing negative role models than they were discussing positive role models, sharing examples of doctors they absolutely did not want to be like.

Identified role models

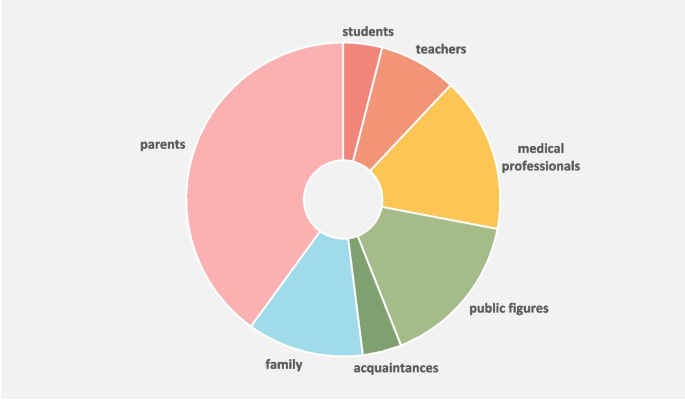

After this initial hesitation, the alumni all identified several people who, in retrospect, may have served as role models during medical school. We grouped these into seven categories, as shown in Fig. 2 Role models of URiM alumni during medical school.

The majority of the identified role models consisted of people from the alumni’s personal lives. To clearly distinguish these from their role models in medical school, we henceforward split the role models into two categories: role models from inside medical school (students, teachers, and medical professionals) and outside medical school (public figures, acquaintances, family, and parents).

Role models of URiM alumni during medical school

In all cases, what attracted alumni to their role models was the fact that they formed a reflection of the alumni’s own goals, ambitions, norms and values. For example, a medical student who highly valued taking time for patients named a doctor as their role model because they had witnessed them taking time for their patients.

Role models as a mosaic

Analysing the alumni’s role models showed that they did not have one all-encompassing role model. Instead, they combined elements of different people to create their own unique, fantasy-like role model. Some alumni just implied this by naming multiple people as role models, but a few of them explicitly described it, as illustrated by the quotes below.

“I think that in the end your role model is like a mosaic of the different people you meet.” [R8].

“I think that in every course, during every internship, I met someone that made me go you’re so good at what you do, you’re such a great doctor, or you’re such a great person, or I’d really like to be like you, or you’re handling that physical exam so well, so I can’t really name one person.” [R6].

“It’s not like having one major role model whose name you’ll never forget, it’s more like: you’ve met so many doctors, you compose a kind of average role model for yourself.” [R3].

Representative role models

The participants acknowledged the importance of similarity between themselves and their role models. Below is an example of a participant who agreed that a certain degree of similarity is a substantial part of what makes a role model.

“You’re more likely to take someone’s word if they have a similar background as you.” [R3].

We found several examples of similarities that alumni deemed useful, such as similarity in gender, life events, norms and values, goals and ambitions, and character.

“You don’t have to be similar to your role model in terms of appearance, but you do have to have similar characters.” [R2].

“I think that it is important to have the same gender as your role model – women have a bigger impact on me than men.” [R10].

Alumni themselves did not bring up shared ethnicity as a form of similarity. Upon being asked about the added value of having a shared ethnicity, participants answered reluctantly and circuitous. They emphasized that there are more important grounds for identification and social comparison than shared ethnicity.

“I guess that on a subconscious level it would’ve helped if there had been someone with a similar background, ‘like attracts like’. If you have the same background, you have more in common, and you might be more prone to take somebody’s word or be more enthusiastic. But I don’t think this should make all the difference, it should be about what you want to achieve in life.” [R3].

Some participants described the added value of having the same ethnicity as their role model as ‘showing that it is possible’ or as ‘instilling confidence’:

“It may make a difference if they are non-western compared to western, because it shows that it is possible.” [R10].

“For a while it did feel like I needed Moroccan role models. But looking back I don’t think that I needed to see these role models, because I already believed that it existed. […] But having more similarities does kind of give you that extra confidence, like: this is not an illusion that I have. And that things will be okay in the end.” [R8].

Role model functions

In analysing the responses to ‘Why was this person your role model?’, we found that different role models qualify as such for different reasons: either exhibiting professional behaviour or serving as a source of motivation. Interestingly, these ‘reasons to be considered a role model’ were consistently attributed to either role models inside or outside medical school.

“A role model can have different purposes: you can aspire after a certain position, but also after personality traits like work hard or being nice to someone.” [R10].

Role models inside medical school

The function that role models inside of medical school fulfilled for URiM alumni can be summarized as exhibiting professional behaviour. The examples were manyfold and included demonstrating clinical skills, having great teaching skills, interacting with students, and maintaining a healthy work-private life balance. Below is an example of an alumnus whose role model was a surgeon who displayed example behaviour and who they admired.

“… that man, he was just kind of like a… a real personality whenever he entered a room, and also very funny. But most of all, and that’s something I hadn’t seen before him or since him, that he really took students by the hand.” [R7].

Role models outside medical school

Role models from outside medical school were considered as such predominantly because of shared norms and values, and to a lesser extent due to specific career paths or professional accomplishments. The majority of URiM alumni did not have role models in their personal life who made them pursue a medical career.

Parents were a source of inspiration and motivation to work hard in medical school for two main reasons. First, parents’ immigration history was often named as a source of inspiration to work hard and persevere. As immigrants, be it migrant workers or refugees, they fled their home country and overcame adversity to offer their children a better future.

“My role model is my mother. She is such a strong woman, she’s been through a lot, fled her country with two young children, a new country, a new language, a new culture, new norms and values, she studied, she raised us, and she is still here for us day and night. She inspires me to always try my very best.” [R6].

Second, parents’ socio-economic status sometimes forced URiM alumni to study hard, because additional tutoring was not financially an option.

“It must have been hard on my parents too, because financially… I remember us having a lot of discussions about the costs of private tutoring. So, it was like: just start by doing your homework properly and then we’ll see.” [R8].

Identified Theme: Lack of Ethnic Diversity in Medical School

The URiM alumni spontaneously brought up similar topics, resulting in three identified themes: student life and moving out, bi-cultural identity, and a lack of ethnic diversity in medical school. These all alluded to how URiM alumni experienced being a minority in medical school and how having more representation could have changed their experience of being ‘different’. Below we therefore focus on their experienced lack of ethnic diversity in medical school. This lack of ethnic diversity among fellow students and teaching staff made them feel uncomfortable, socially excluded, or hindered their professional development. Most of these experiences occurred during workplace learning.

“I definitely think it would have helped it there would have been more doctors with a minority background.” [R6].

Several participants shared how they were not accepted into certain highly regarded residency training programs, such as general surgery. One extreme example of this was an older participant who was denied a residency position, based explicitly on his migration background.

“He sat next to me and said: ‘Son, I’ll be honest with you: I could mess with you and hire you temporarily, but you won’t make it. You won’t get in. Not because you’re too old, but because you’re a foreigner. You should go and do something else.’” [R4].

Other examples of hinder attributed to a being an ethnic minority in medical school included people making assumptions about participants’ native language, ethnicity, or religion, for example being asked to interpret for people from a different country than their own. Despite introducing this topic, most participants appeared remarkably unfazed about the incidents and assumed that it would be just a matter of time before medical schools will be more ethnically diverse. The participant in the quote below noticed a shift in attitude towards URiM students:

“I think the medical profession and medical education are swiftly changing […] in favor of students with underrepresented backgrounds. […] having a different cultural background is starting to become a positive asset. I’m noticing this in job interviews, like we’re seeing that patients are comfortable around you because of how you look. […] In five years, I think medical education will be drastically different.” [R8].