When school let out on those days, Hurd and his friends at Worthing High School would pile into their vehicles or line the streets of Sunnyside, preparing for the crosstown pilgrimage to the old Jeppesen Stadium. They hitchhiked if they had to.

“It seemed just about every able body in Sunnyside was Third Ward-bound, and most of the cars and their passengers — hitchhikers, too — were adorned with some kind of green-and-gold trinket,” he writes.

MORE FROM CHRIS GRAY: How Nicole May became the vinyl record queen of Galveston County.

Worthing, and nearly 100 other high schools like it, once belonged to the Prairie View Interscholastic League, the organization in charge of Black high school athletics in Jim Crow Texas between 1920 and 1970. Now open through July 2 at Galveston’s Bryan Museum, a new exhibit based on Hurd’s book (and sharing its title) examines the complicated legacy of Texas high school football’s most unsung — and fascinating — chapter.

“Not being from Texas, and being born in ’75, I wasn’t really aware of this part of Texas history, and I’m so glad that I was able to learn about it” says the Bryan’s Eric Broussard, who co-curated the exhibit with Hurd.

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

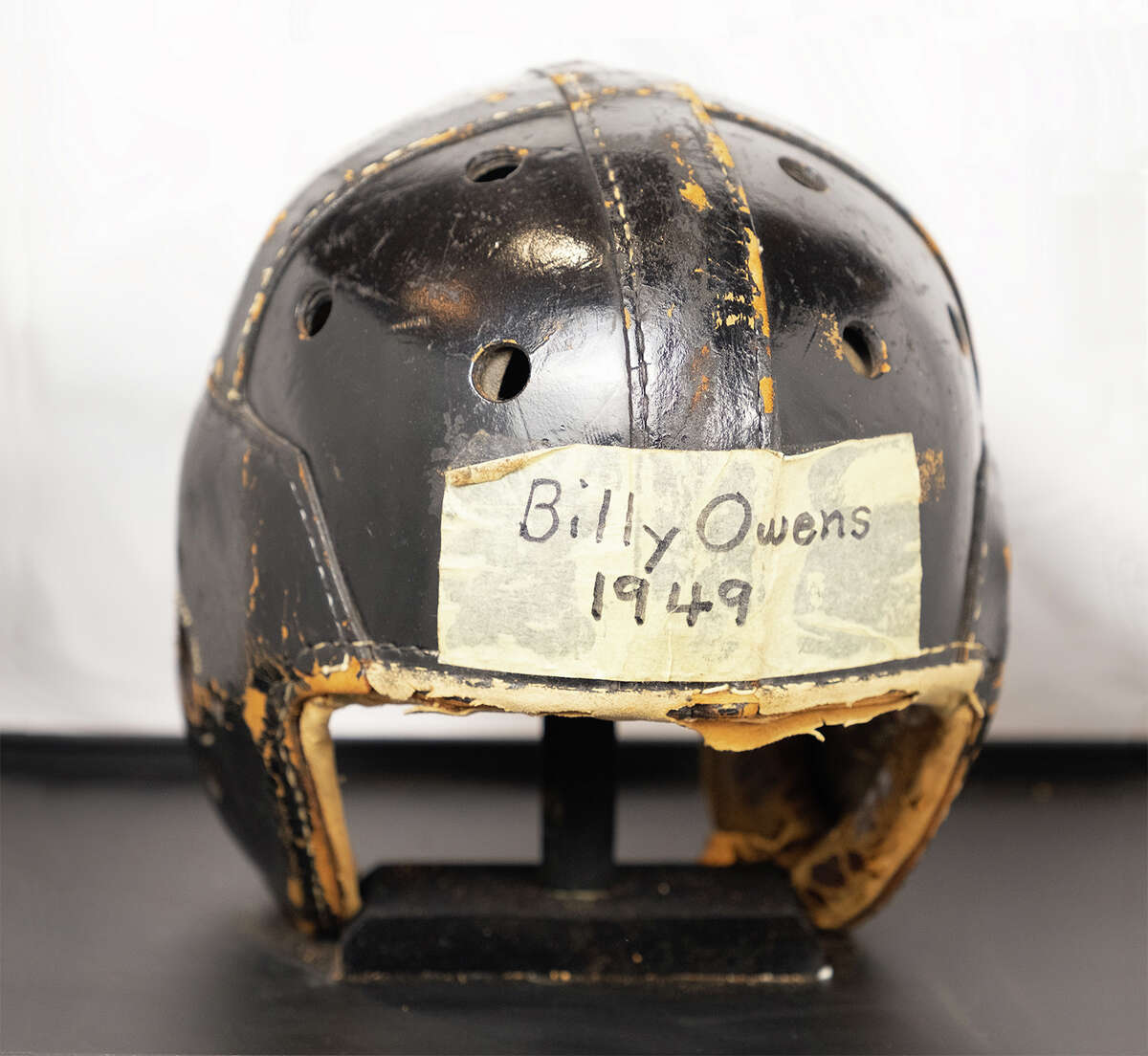

Besides playing their games earlier in the week — Friday nights being reserved for the white teams who often shared district facilities with their Black counterparts — the PVIL schools enjoyed a fraction of the funding granted to white schools and were often forced to make do with hand-me-down equipment. (Even jockstraps, Hurd notes.) But they also fostered an incredible amount of school and community pride, as well as a breathtaking bounty of talent that produced several NFL Hall of Famers and many, many more local locker-room legends.

“So many of the guys that I talked to, it was the first time they had ever been interviewed about their playing careers in high school — to me that was the real treat,” Hurd says. “They were so happy to talk about what they had done and the schools they had gone to.”

So much material, so little room

“Thursday Night Lights” squeezes a wealth of material into the Bryan’s upstairs exhibition hall: a photo of three players from Hopewell, (near Paris) circa 1930; a leather helmet from 1949; a case full of cleats; team pictures of state champions Austin Anderson, Baytown Carver and Beaumont Hebert; jerseys, sweaters and letter jackets from Houston Independent School District stalwarts Kashmere and Yates as well as the long-closed Galveston Central, Conroe Washington and La Marque Lincoln; and photos of legendary coaches like Anderson’s Ray Timmons, Yates’ “Pat” Patterson — who helped organized the PVIL’s playoff system, which launched in 1940 — and Conroe Washington’s Charles Brown, whose wife laundered and mended her husband’s players’ uniforms because the school district wouldn’t provide the team with a washing machine.

“That was the kind of community support most of those schools got back in the day,” says Hurd, a former sportswriter for the Houston Post and Austin American-Statesman.

And there’s a lot more where this came from. The seeds of Hurd’s book were planted in 2007, when he attended the PVIL Coaches Association’s annual Hall of Fame banquet and met Robert Brown, the organization’s director. Some items in “Thursday Night Lights” were donated by the Bell County Museum and Galveston’s Old Cultural Center, but the bulk of the collection belongs to Brown, whom Hurd says would love to find it a permanent home. (In the meantime, he adds, Brown has “been collecting all of this stuff and stashing it in the second floor of his house.”)

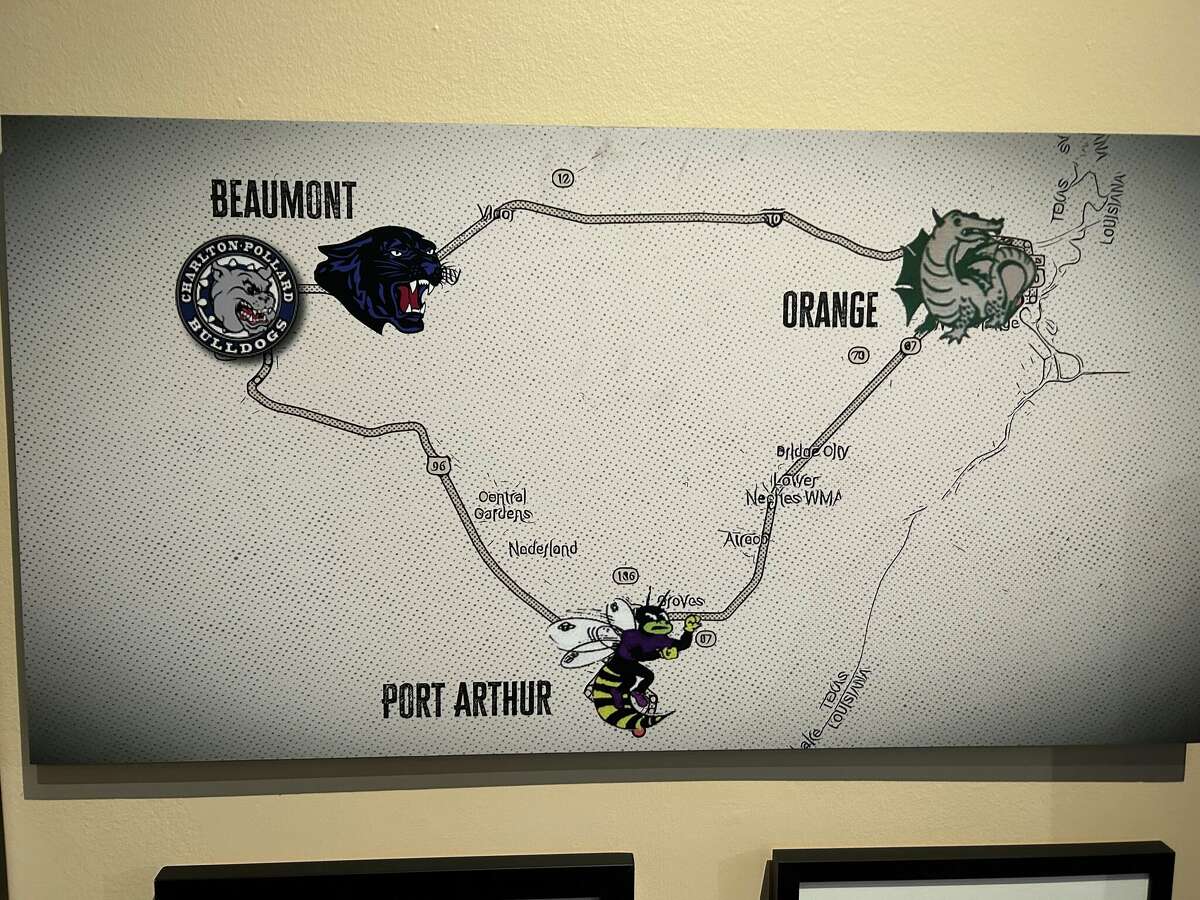

Some Texas colleges began integrating as soon as the mid-1950s, shortly after Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott kindled the civil rights movement, but most took well into the 1960s. The University of Houston began integrating its athletics program in 1964, the first major Southern college to do so; it took until 1967 for Texas A&M University to field its first Black football player and 1970 for the University of Texas. A few standouts like Beaumont Charlton-Pollard’s Bubba Smith — later known for his role in Miller Lite TV commercials and the “Police Academy” films — caught on at out-of-state schools (Smith starring at Michigan State), but throughout its life span, the PVIL was a direct pipeline to “the mighty SWAC.”

When: Through July 2; panel discussion 5:30 p.m. June 15

Where: Bryan Museum, 1315 21st, Galveston

Details: $5-$14; 409-632-7685; thebryanmuseum.org

In the Southwestern Athletic Conference, schools such as Texas Southern University, Grambling State University, Southern University and Prairie View A&M University built powerful programs from the steady stream of PVIL-schooled players. More than a few alumni then turned pro, especially after the American Football League began challenging the NFL’s dominance in the early 1960s. AFL owners were only too happy to begin “raiding” historically Black colleges and universities, Hurd says.

“The NFL at that time still wasn’t happily taking Black college players or Black players in general, but the AFL is trying to compete with the NFL,” he explains. “They see this talent source that the NFL is ignoring, and they’re like, ‘Yeah, we can do this.’”

‘Hostile takeover’

But even reaching the pinnacle of the sport, these players could find their opportunities limited. In 1968, the Oakland Raiders made Eldridge Dickey, out of Houston’s Booker T. Washington High School, pro football’s first-ever Black quarterback chosen in the first round, but he never threw a regular-season pass in the pros. The team forced him to play wide receiver, and it would be another generation or two before NFL owners and executives fully embraced the idea that a Black quarterback could succeed.

Consequently, the list of PVIL players in the NFL Hall of Fame includes receivers Charley Taylor (Grand Prairie Dalworth) and Hurd’s Worthing classmate Cliff Branch; defensive backs Ken Houston (Lufkin Dunbar) and Dick “Night Train” Lane (Austin Anderson); and linemen “Mean” Joe Greene (Temple Dunbar) and Gene Upshaw (Corpus Christi Coles).

Plenty of other noteworthy names came up short in Canton but made their mark all the same: running back and Pearl Harbor hero Dorie Miller (Waco Moore); University of Oklahoma Heisman finalist Joe Washington (Port Arthur Lincoln); and towering lineman turned professional wrestler Ernie “Big Cat” Ladd (Orange Wallace), whose 6-foot-9-inch life-size cutout scowls back at “Thursday Night Lights” visitors.

Texas public schools began integrating in the mid-’60s, a contentious process that lasted roughly four years. Urban schools mostly desegregated first; small-town and rural schools took longer. Gradually, the PVIL was absorbed into the white-run University Interscholastic League, a process Hurd calls “more a hostile takeover” than a merger. Ultimately, all but a few Black schools shut down, leaving many Black coaches out of a job. Those who managed to catch on at newly integrated schools largely found themselves acting as liaison between Black players and white coaching staffs.

These awkward changes reflected what was happening in the communities that had nurtured many PVIL schools. “I think that kind of crushed a lot of Black culture, at least in terms of practicing it and teaching it,” says Hurd. “Because these games, they were about football, athletics, but they were also about culture. Going to those games was as much a cultural event as they were athletic events.”

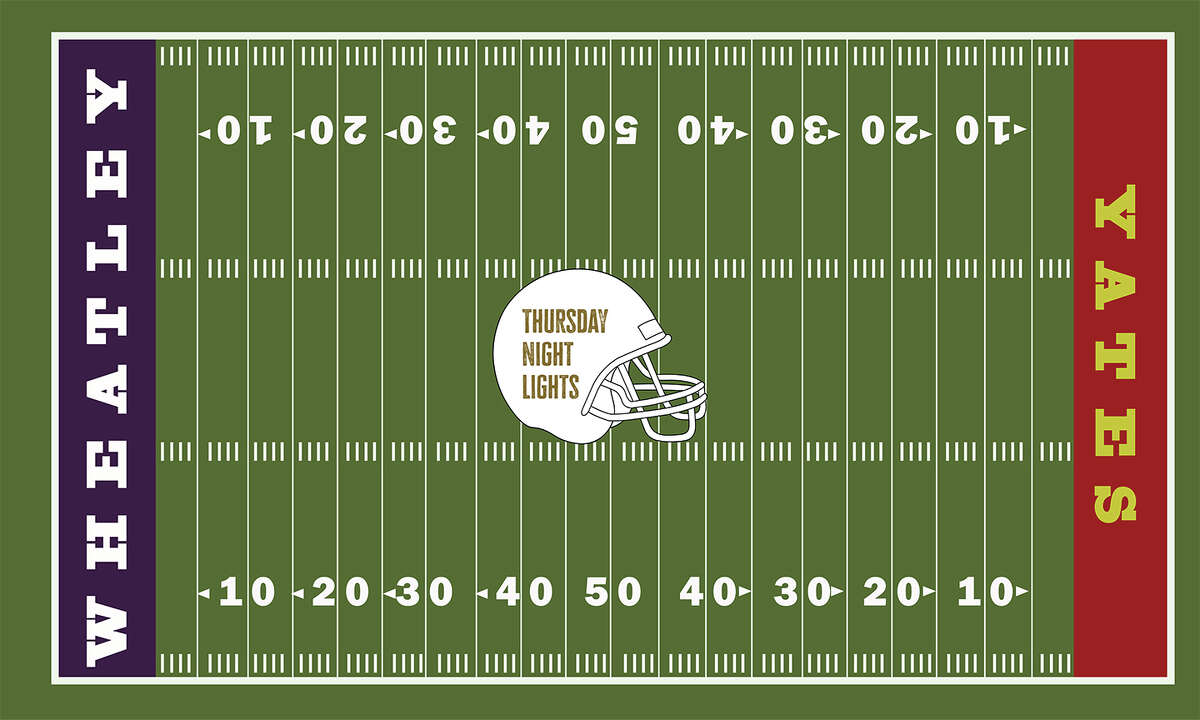

Yates versus Wheatley

Nowhere in “Thursday Night Lights” is this more apparent than the area devoted to the Turkey Day Classic, the Thanksgiving Day rivalry game between Yates and Wheatley. Like the Golden Triangle’s “Soul Bowl” between Beaumont Hebert and Charlton-Pollard, the game could divide families along bitter partisan lines: “in one house, you might have maybe your grandmother went to Booker T. Washington, dad went to Yates, mom went to Wheatley,” Hurd says.

Across Third and Fifth wards, the hours before the game were filled with parades and celebratory breakfasts. Then, upward of 30,000 fans would pour into Jeppesen Stadium, where the University of Houston’s TDECU Stadium stands today. After expanding to accommodate the AFL’s Oilers (this was pre-Astrodome), the capacity grew to more than 40,000; it still wasn’t enough. Fans forced out of the bleachers crowded behind the sidelines. The game was also big enough that it drew the attention of the white-controlled media outlets that otherwise largely ignored the PVIL.

Today, the Turkey Day Classic stands as perhaps the prime example of the PVIL’s impact, both in terms of the play on the field — Yates especially was usually among the league’s top programs — and its importance to Houston’s Black population.

“I was telling the (PVIL’s) story the other night,” says Hurd, who will moderate a discussion of former PVIL players and coaches at 5:30 p.m. June 15. “There was a guy who bought this book and he’s flipping through it. He shows it to his grandson, and he’s flipping through it. He finds his name and he says, ‘Look, I’m in this book.’ That’s the guy that I wrote that book for.”

“In the end,” adds Broussard, “we just want to honor the men who played and coached in the PVIL, and what they contributed to the history of Texas.”

Chris Gray is a Galveston-based writer.