My first memories of Juneteenth began in church. I grew up in a predominantly Black section of Jamaica, in the New York City borough of Queens. Our small congregation at New Bethel Baptist Church consisted of Caribbean immigrants such as my Haitian-born mother, native-born New Yorkers such as me, and migrants from across the South, including Texas. As new parishioners arrived, they transplanted their food, culture, and folkways into our church rituals and traditions.

My mother prided herself on the excellence of her Haitian cooking, especially dishes such as soup joumou, stewed chicken accompanied by rice and beans (black or red), and the sweet coconut dessert she occasionally prepared for other congregants. But we also relished those special occasions at church when the cozy upstairs room that doubled as a kind of banquet hall was filled with the rich aroma of Southern soul food: cornbread, fried fish, red velvet cake.

This was the early eighties, my elementary school years. One Sunday morning, as I sat on a light brown pew in New Bethel’s sanctuary, I was rapt as parishioners from Texas took to the pulpit and told a fascinating story of enslaved African Americans who didn’t hear news of their liberation until Union general Gordon Granger issued an order in Galveston on June 19, 1865, more than two months after Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, in Virginia. I was reminded of my mother’s stories about the Haitian Revolution, in which slaves overthrew French rule and, to much of the world’s surprise, achieved independence in 1804. That uprising inspired emancipation movements around the globe, though it would be another six decades before freedom for the enslaved reached America’s shores. After the service I overheard fervent conversations about slavery and the need to teach young children like me to never forget.

I didn’t know it at the time, but my experience of hearing about Juneteenth was similar to that of untold others across the United States. Juneteenth had been observed in Texas since 1866, and celebrations soon spread to neighboring states. As Black Southerners fled north and west throughout the twentieth century, in what became known as the Great Migration, festivities cropped up across the country. My family didn’t mark Juneteenth at home, but our Texan parishioners never allowed us to take for granted its special meaning. Each year we would commemorate the day, often during a Sunday service and occasionally during vacation Bible school. Only later would I learn that the stories of Juneteenth that I’d heard in church were part of a far more complicated tale.

I’d first discovered Black history through my mother’s stories of our Haitian heritage and culture, traditions that she’d brought with her to a mid-sixties America convulsed by a civil rights revolution. Essential texts from that movement were found throughout my home: The Autobiography of Malcolm X; various works by Angela Davis, the innovative thinker who was on the FBI’s Most Wanted list in 1970; and Martin Luther King Jr.’s final book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? I vividly recall watching the Roots television miniseries, which offered a groundbreaking examination of slavery in American popular culture. Juneteenth introduced a new layer to this story. I imagined myself as part of the Black Texas community, which dared to believe in dreams of freedom that were once considered impossible.

As I grew older, my interest in history expanded. The more I found out, the deeper I yearned to go. Slowly I came to realize that history was not just about the past. The stories it tells help us make sense of the here and now—and might shape the future. I eventually became a professor, my teaching and research interests firmly planted in the twentieth-century civil rights and Black Power movements.

In 2015 I accepted a position at the University of Texas at Austin, and once I arrived, my understanding of Juneteenth became more intimate. I witnessed local celebrations in Austin, in which Black Texans acknowledged the day’s importance but also wrestled with its contradictions, knowing that real freedom had not in fact been achieved that day in Galveston—it was still a work in progress. While Texans celebrated Juneteenth with a particular zeal, many Americans still did not have the faintest clue about its origins, historical import, or contemporary resonance. That was, until an improbable series of events transformed Juneteenth into a national symbol.

George Floyd’s public execution by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020, sparked months of demonstrations that swelled into one of the largest social justice movements in American history and elicited an unprecedented collective outpouring of racial grief. Against this backdrop, I was one of many who began to examine Juneteenth anew. I published a CNN opinion article headlined “Make Juneteenth a National Holiday Now,” arguing in part that Juneteenth offers America a new origin story. Black people are largely absent from our national narratives. Juneteenth, I suggested, offered an opportunity to correct that.

In some ways Juneteenth can be read as a response to Frederick Douglass’s searing 1852 speech in Rochester, New York, now known as “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Douglass, a formerly enslaved Black man from Maryland who became arguably the most important activist of the nineteenth century, assailed celebrations of freedom in a land scarred by slavery. “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine,” he said to the audience. “You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

On June 17, 2021, roughly a year after Floyd’s killing, Juneteenth became an official U.S. holiday, signed into law by President Joe Biden. It was the first new federal holiday since Martin Luther King Jr. Day was enshrined, in 1983, and a signal achievement in American history—drawing the country one step closer to publicly acknowledging its original sin of slavery.

Yet the real history of Juneteenth remains largely unknown—the myriad ways in which Black freedom was persistently sabotaged, beginning with Granger’s original order and continuing through today—at a moment when our national narrative is hotly contested. The teaching of history is under attack, which lends more urgency to an earnest reckoning with the meaning of Juneteenth. What are we celebrating when we observe it, and should we be celebrating it at all? Is it actually an indictment of America? A repudiation of the Fourth of July? Is it a day worthy of veneration, of shame, or of both?

When General Granger first sailed into Galveston in June 1865, he was accompanied by roughly two thousand troops. At the time Galveston was the most populous city in Texas, with a bustling and lucrative port managed partly by Black workers who transported goods and gossip from around the world. Granger and his staff commandeered a villa in town and set out on the impossible mission of bringing a semblance of order and security to the largest secession state of the newly restored union. The mood was dark, with cities and rural hamlets still reeling from the physical and economic devastation wrought by the war.

About a month earlier, the Confederate Army had won a battle at Palmito Ranch, outside Brownsville. That clash, the last major action of the Civil War, had been waged more than a month after Lee’s surrender in Virginia. Without the forceful appearance of Union soldiers, Black Texans had remained imprisoned within the convulsive clutches of a dying Confederacy.

The stories of how General Order No. 3 was relayed to Galvestonians vary, but Granger likely read the order aloud in a public meeting designed to spread the message to as many people as possible. The words “All slaves are free” served as a declaration of independence for some and a provocation to others. Granger and his troops often encountered a violent, anxious, fearful, and vengeful white population, including Confederate soldiers and sympathizers who engaged in reckless attacks and looting in parts of Texas.

Granger’s order was based loosely on Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. (The Thirteenth Amendment, which made slavery unconstitutional, wasn’t ratified until December 6, 1865.) The order first declared that the formerly enslaved were free based on “absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property” between Black people and those who had presumed legal ownership of them. This is the happy news upon which most Juneteenth celebrations are based. It’s also an oversimplified tale of what happened that day.

A common view about Juneteenth, in both Black and white communities, is that Black folks in Galveston and around Texas were slow to hear or fully grasp the news about the Civil War’s end and the arrival of liberty. This is the story I was told in church. But that’s not entirely true. Some portion of Black Texans, especially those working in the port of Galveston, knew that the tide of the war had long ago turned in favor of Union troops. They’d also probably caught wind of the Emancipation Proclamation from travelers disembarking on the wharves. Further, they’d likely heard what must have seemed to be fantastical tales about regiments of Black soldiers in the Union Army.

News of impending freedom had almost certainly reached other parts of Texas, when enslaved African Americans from the Deep South were transported to the Lone Star State during the war. (Texas was a haven for white slave owners fleeing Louisiana and other areas of the Confederacy being conquered by Union troops.) But the news held little practical meaning so long as the state remained under Confederate control. The arrival of some two thousand federal troops appeared to mark an end to white rule over Black Texans.

But Granger’s order limited and undermined the very freedoms that it promised. The relationship between former masters and the enslaved would now evolve into a vague contract between employers and hired labor. “The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages,” read the order. But how could Black Texans enjoy freedom while remaining on plantations? Would they be allowed to leave, travel, or reunite with loved ones? Were they forbidden from becoming entrepreneurs and landholders?

Further, Black men and women were warned not to flock to military posts. Since 1863, when Black men were allowed to enlist in the Union Army, its military posts had become beacons for freedmen. The sight of blue uniforms liberating secessionist territories often meant the promise of food, clothing, and reading materials. Granger’s warning that Black Texans “will not be supported in idleness” on military posts or elsewhere was an admonishment, suggesting that they could not rely on federal troops, whether those Texans were seeking protection, searching for news about family and friends, looking for work, or in need of food. The troops were there to enforce liberation, but they would not necessarily support those trying to carve out a new life.

This is why, even after Granger arrived, many Black folks responded to the news of freedom cautiously, fearing reprisals. Yet as word spread, some did walk away from plantations. Others rejoiced, exulted, and stayed put while planning their next moves.

The park, Thompson explained, serves as a living memorial to generations gone by. It’s also a repository of a story that is just beginning to receive its due.

Fears among Black Texans were often borne out. In the ensuing months, the beginning of the period that would come to be known as Reconstruction, racial violence spread. In one town, white Texans whipped dozens of formerly enslaved people who celebrated the news of emancipation too enthusiastically. White attacks against free Black people ranged from verbal harassment and intimidation to physical assaults and even murder. Black Texans in Galveston and other parts of the state navigated a new landscape at times more dangerous and volatile than the one they’d left behind.

The backlash of many white residents against the idea of Black citizenship and dignity would become a normal feature of Texas’s political landscape, a legacy that persists today. Just as limitations on Black freedom were baked into Granger’s emancipation announcement, racial discrimination became embedded in public policies that propagated unequal housing and employment opportunities, wealth gaps, educational and residential segregation, police brutality, and political disenfranchisement. Black Codes in Texas and throughout the South prevented African Americans from voting, securing fair labor contracts, attending racially integrated public schools, or owning land. For many years after Granger’s arrival in Galveston, freedom could not be publicly enjoyed in some parts of Texas, even on Juneteenth itself.

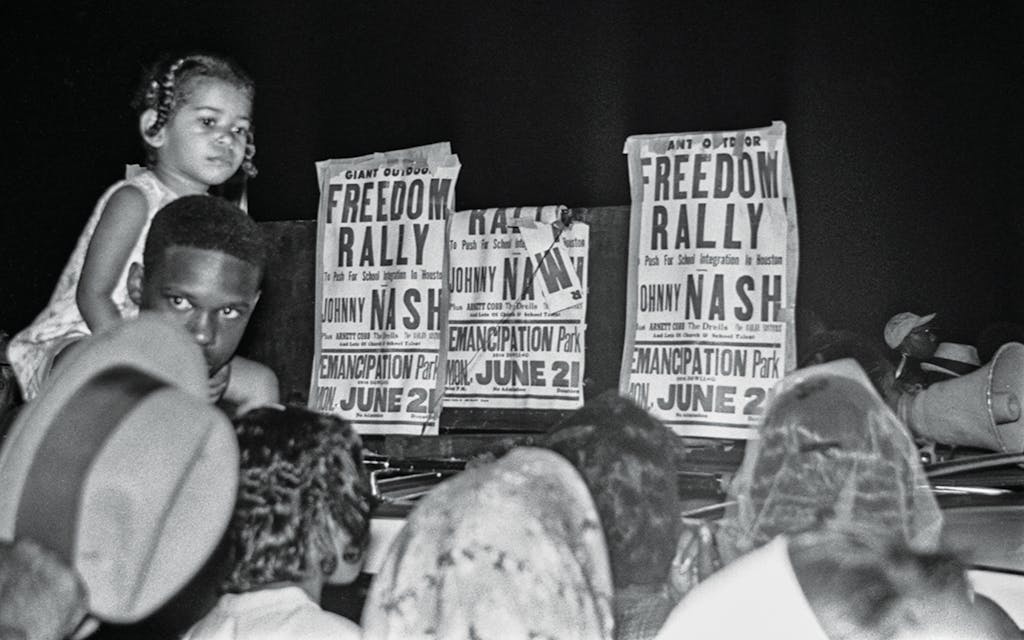

On a chilly day this past fall, I arrived in Houston’s Emancipation Park and was joined by Erika Thompson, an archivist and historian who serves as community liaison at the African American Library at the Gregory School, which once housed the first Black school in the city. Thompson had agreed to show me around the park, which sits just south of downtown in Third Ward, long a center of the city’s Black community. Established in 1872, the park is among the oldest in Texas, created by formerly enslaved locals who wanted a place to commemorate Juneteenth.

Though the inaugural celebrations were relatively small, today they are citywide affairs that feature appearances and speeches by elected officials, religious and civic leaders, and a who’s who of Black Houston. As Thompson and I walked the grounds, she pointed to the abstract mosaic sculptures that honor four of the community leaders who raised money to purchase the ten acres of land: the Reverend David Elias Dibble, Richard Allen, Richard Brock, and John Henry “Jack” Yates. Located at the four corners of the park, the sculptures are the work of the local artist Reginald Adams.

The park, Thompson explained, serves as a living memorial to generations gone by. It’s also a repository of a story that is just beginning to receive its due. The founders of Emancipation Park were all born into bondage. As pastors, tradesmen, political leaders, husbands, and fathers, they helped make Houston a wellspring of Black social, political, economic, and religious life in Texas.

After emancipation Richard Allen quickly became one of Houston’s most important political leaders. A talented carpenter and architect, he served as an agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau, as a voter registration supervisor, and as an elected state representative.

Allen designed Antioch Missionary Baptist Church, which was led by Jack Yates, who had become a minister and activist in the late 1860s. Yates also played a leading role in the founding of the Houston Baptist Academy, a precursor to Texas Southern University.

A third sculpture in the park honors Richard Brock, who established a successful career as a blacksmith in Houston at a time when barriers to African Americans’ entrepreneurship were almost impossibly high. He later helped found the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Lastly, David Elias Dibble was a self-taught preacher and founder of a Freedmen’s Methodist congregation, now called Trinity United Methodist Church. Dibble collaborated with the Freedmen’s Bureau, helped create a school within his church, and served as a trustee for the Gregory School.

These four men and their contemporaries provided an incubator for educational advancement, cultivated tight-knit religious communities, and built a thriving political movement that propelled a number of formerly enslaved Black Texans into positions of power that made them prominent figures within the racially integrated Republican Party.

After exploring the park grounds, I went inside the cultural center and gazed upon gorgeous photographs of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Black Houstonians. One image depicts a well-to-do family outside a tidy home. Another shows a group of some thirty women and men during a Juneteenth celebration in the late 1800s. They look both prosperous and circumspect, with some older men doffing their hats and younger women wearing white, exhibiting a kind of grace that racist stereotypes of the era insisted that Black people could never possess.

Studying these photos, I was struck by how much Black Texans were able to achieve in the years immediately after the abolition of slavery. Their efforts paved the way for others. Fort Bend County, just southwest of Houston, became such a significant base of Black political activism that unsympathetic white Texans characterized it as part of the “Senegambian district,” a mocking reference to a region in West Africa. Black residents served as district clerks, constables, justices of the peace, and county treasurers.

The creation of Emancipation Park represented a belief in the power and promise of a new Texas, one in which Black citizenship and dignity could be celebrated, even as full equality was still just a dream.

One of Opal Lee’s early memories of Juneteenth was formed when she was twelve years old. On June 19, 1939, an angry mob of some five hundred gathered outside her family’s home, in a predominantly white Fort Worth neighborhood. The mob, seemingly unaware of the day’s significance, simply wanted the Black family gone. She and her parents and siblings fled, and their house was burned. Her parents purchased another home and never mentioned the incident again.

Lee, now 96, grew up to become a teacher and later a community activist. She had fond memories of attending Juneteenth celebrations as a girl, and one of her goals was to see the day recognized as a federal holiday. In 2016 she decided to lace up her tennis shoes and organize a march from her home in Fort Worth to Washington, D.C., attracting national media attention in the process. Lee’s walk eventually led to the White House, where she proudly stood beside President Biden as he signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act. Lee has become something of a household name, known as the “grandmother of Juneteenth.” But she wasn’t alone in her efforts.

Lawrence Thomas, a Galveston native, also received an invitation to the White House, although without the fanfare that accompanied Lee’s visit. Thomas’s roots in Galveston trace back to the days of slavery. Michel Menard, one of the founders of Galveston, owned Thomas’s great-great-grandfather. Thomas’s ancestors helped build the city and were there when Granger stepped onto the island. His father began organizing Juneteenth celebrations in the city roughly four decades ago.

All of us, no matter our politics, tend to reduce and oversimplify the historical record. Reality is messier and more nuanced.

Lee and Thomas are profiled in Juneteenth: Faith and Freedom, a 2022 documentary directed by my friend and fellow UT-Austin professor Ya’Ke Smith. The film is an incisive, personal, and moving examination of Juneteenth through the eyes of Black Texans who have helped push the history of that day—and all the days that have followed—to the forefront of the national imagination and political conscience.

I recently watched a screening of the film at the Lady Bird Johnson Auditorium on UT-Austin’s campus. A group of around forty gathered in the cavernous building—more students trickled in as the film began—and the crowd was deeply engaged, reverential even. At one point we saw images of Lee and Thomas at the White House. As Thomas recounted traveling to Washington with his daughter—he shared his family’s story with the president, he said, and cried “quite a bit”—I found myself emotionally undone, tears streaming down my face.

While researching Juneteenth, I was often reminded of the Harvard University historian Annette Gordon-Reed, a native Texan who integrated her elementary school as a first grader in Conroe, north of Houston. (The town now has a school named in her honor.) In her 2021 book, On Juneteenth, which blends history with memoir, she movingly describes her family’s annual Juneteenth celebrations, complete with homemade tamales, fireworks, barbecue, and red soda.

In her research, Gordon-Reed uncovered no shortage of horrors experienced by Black Texans, both before and after slavery’s official end. But in her telling, she offers a provocative correction to the all-too-common Manichaean portrait of Texas and America. A nation, state, and community can be two things at once, both abolitionist and proslavery, integrationist and Jim Crow. All of us, no matter our politics, tend to reduce and oversimplify the historical record. Reality is messier and more nuanced. Slavery is neither an aberration nor the whole of the national character.

Our telling of American history has for far too long leaned toward the romantic when it could have benefited from the prosaic. And though we should not gloss over the ugliest truths, progress is also real and should be celebrated. One of Juneteenth’s most important lessons is that history is about not just the country’s triumphs but more often the relentless struggle necessary to achieve a more perfect union.

This ideal is profoundly evident in the stories of individuals whose lives feature both grotesque instances of violence and sublime moments of love. Their memories encapsulate the nation’s arduous journey out of slavery toward a freedom we are still fighting to realize. Their undaunted faith in an expansive vision of dignity and citizenship should ennoble and inspire us all.

Peniel Joseph is the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values at the University of Texas at Austin. His most recent book is The Third Reconstruction.

This article originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Two Meanings of Juneteenth.” Subscribe today.

Image credits: Statue: Elaine Thompson/AP; General Orders No. 3: National Archives/Getty; Freedom Rally: RGD0006N-1965-2111-017/Houston Public Library/Houston Post; Biden: Evan Vucci/AP; Lee: Paul Moseley/Fort Worth Star-Telegram/Tribune News Service via Getty; Brass band: Godofredo A. Vásquez/Houston Chronicle/AP; Granger: Library of Congress