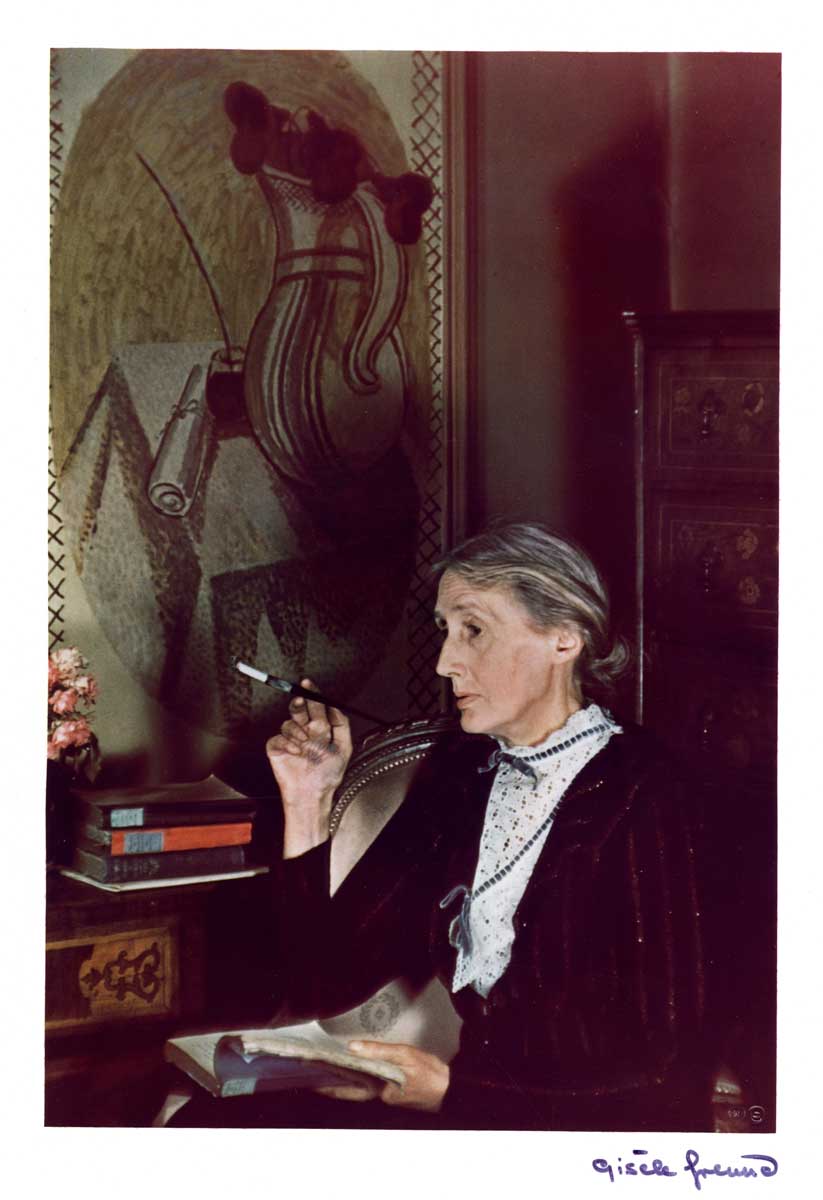

Born Adeline Virginia Stephen in London in 1882, the writer who the world would come to know as Virginia Woolf came from a distinguished artistic and literary family. Her father was the respected Victorian man of letters Sir Leslie Stephen, and her mother, Julia, had been a model for the Pre-Raphaelites and for her aunt, the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. As an adult, Virginia Woolf followed in her father’s footsteps by cleaving to the literary side of her heritage. However, she developed a distinctive writing style and voice that was entirely her own. From her debut to her last novel, here we explore just seven of her most notable novels…

The Voyage Out was Virginia Woolf’s debut novel, published in 1915, which, in itself, makes this one of her most notable novels. It tells the story of Rachel Vinrace, a young woman who has led a fairly sheltered life until she embarks on a journey to South America with her aunt and uncle. Her aunt, Helen, in particular, becomes a mentor figure for Rachel, helping her to explore more of life than she has hitherto seen from her father’s house. Together, Rachel and Helen meet more English tourists staying at a hotel. Among the guests is Terence Hewet, with whom Rachel falls in love.

The novel, therefore, seems conventional enough: a romantic novel constructed around the holiday abroad trope, such as fellow Bloomsbury member E.M. Forster uses in his novel A Room with a View (1908). However, unlike Forster, Woolf has chosen a more tropical destination for her heroine than the beauty spots of Europe. As Peter Fifield has argued, this allows Woolf to subvert our expectations of a seemingly conventional narrative by adding an element of danger. Will Rachel and Terence – and their burgeoning relationship – survive in this new climate?

Another notable feature of The Voyage Out is the cameo appearance made by Richard and Clarissa Dalloway at the start of the novel. These, of course, are characters Woolf would return to in her short fiction and in a later, more famous novel.

2. Jacob’s Room, 1922

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Virginia Woolf followed up The Voyage Out with her second novel, Night and Day, in 1919. Stylistically, Night and Day has much in common with The Voyage Out; both are fairly conventional realist novels. It was not until the publication of Jacob’s Room in 1922 – that seminal year for literary modernism, in which T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and James Joyce’s Ulysses were also published – that Woolf found her own distinctive, experimental style of writing.

This was facilitated when, in 1917, Virginia and her husband, Leonard, set up the Hogarth Press. Previously, Virginia Woolf’s novels had been published by her half-brother Gerald Duckworth’s Duckworth Press. Woolf later revealed that, as a child and as an adolescent, she had been sexually abused by both Gerald and George Duckworth. And she also felt pressured to write novels that would be commercially successful in order to continue being published by Duckworth Press, preventing her from trying more experimental modes of writing. However, with the establishment of the Hogarth Press, she was free to write exactly as she chose – precisely what she did in writing Jacob’s Room.

Jacob’s Room might be considered an interrupted bildungsroman, cut short by the First World War. (One criticism of Night and Day that had particularly wounded Woolf was Katherine Mansfield’s observation that Woolf had failed to make any mention of the war. In Jacob’s Room, Woolf rights that wrong.) The reader follows the eponymous Jacob from childhood through to his studies at Cambridge and early adulthood, including trips to Italy and Greece. Despite the emphasis on Jacob, however, he is largely presented through the perspectives of other characters and often in an elegiac vein. The horrors of the Great War would recur throughout her later fiction, beginning with Jacob’s Room.

The next novel Woolf published after Jacob’s Room was Mrs Dalloway, and here she is in full stylistic command. Though Woolf famously (and conceivably with more than a hint of jealousy) thought James Joyce an overrated writer, she did take inspiration from his circadian novel Ulysses, set on 16th June 1904. Likewise, in writing Mrs Dalloway, Woolf chose to set the events of her novel on one day in June (possibly 13th June). And, also just as Ulysses has inspired the celebration of “Bloomsday” every year, so too is Mrs Dalloway celebrated every June.

Mrs Dalloway centers around the different yet strangely interconnected lives of Clarissa Dalloway and Septimus Warren Smith. While Clarissa prepares for the party she is to hold that night and reminisces about old friendships, Septimus struggles with shellshock following his experiences as a soldier during the First World War. United by the city of London, their lives are at once separated by wealth and class, and yet Woolf draws them together into an interconnected narrative. Mrs Dalloway is a novel of great beauty and humanity and remains one of her most famous works the world over.

4. To the Lighthouse, 1927

Published just two years after Mrs Dalloway, in 1927, To the Lighthouse is perhaps Virginia Woolf’s most accomplished novel. The novel is comprised of a tripartite structure: the first section is titled “The Window,” the second “Time Passes,” and the third “The Lighthouse.” Following the Ramsey family across a period of ten years in which beloved family members are lost, and war breaks out across the world, the novel begins at the family’s holiday home on the Isle of Skye, modeled closely on Talland House, where Woolf herself spent many happy summers as a child, in St. Ives, Cornwall.

Set over a single day, “The Window” follows the Ramseys and their guests going about their day before Mrs. Ramsey holds a dinner party. The social cohesion achieved through this moment of commensality is, however, soon broken, as “Time Passes” charts the degradation of the holiday home (which has been left to stand unoccupied) over a period of roughly ten years, during which family members die, and the First World War breaks out. This middle section is a wildly experimental piece of writing. The human focus is removed, allowing Woolf to range among viewpoints and present human suffering within a wider non-human context, thus challenging our anthropocentric presumptions without ever minimizing the reality of human pain.

The novel’s final section shows a depleted Ramsey family returning to their holiday home on the Isle of Skye, along with their guest, the artist Lily Briscoe, from the novel’s beginning. While the Ramseys make the long-delayed trip over water to the nearby lighthouse, Lily Briscoe paints in the garden. A meditation on love, family, and female artistic vision, To the Lighthouse is a novel as elegant as it is heartfelt.

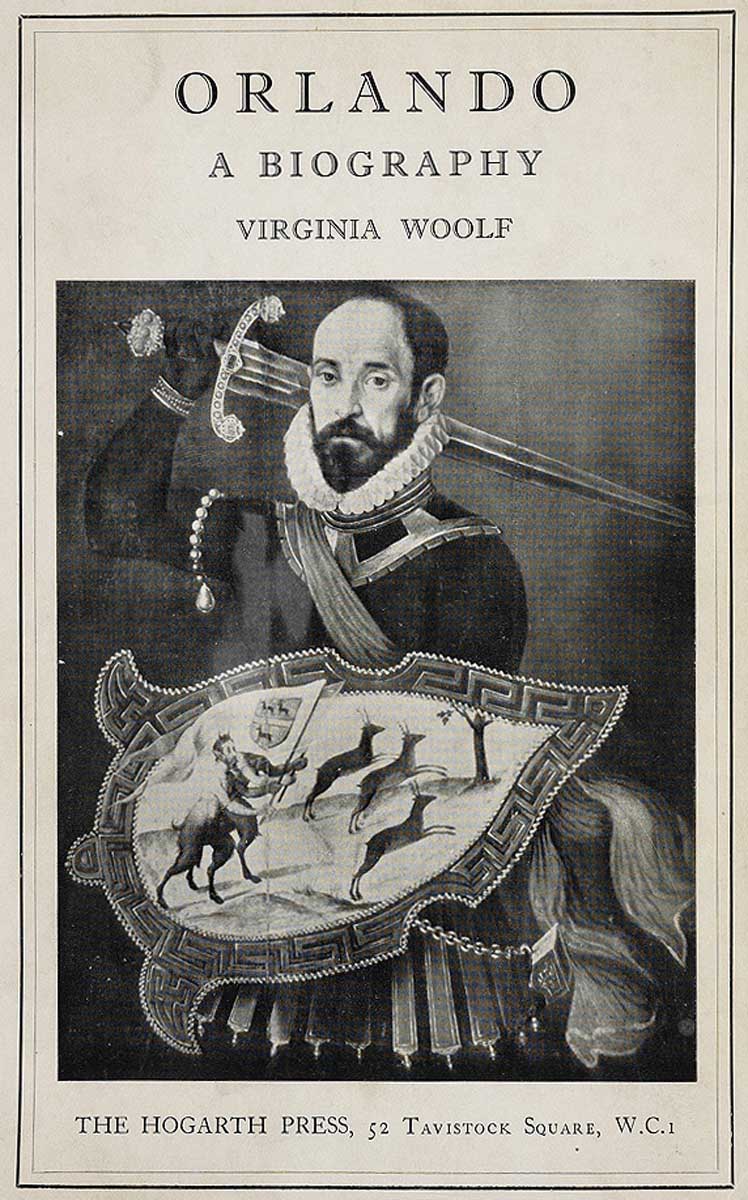

Having finished To the Lighthouse, Woolf wrote that she felt “the need of an escapade after these serious poetic experimental books, […] to kick up my heels & be off.” The “escapade” she then went on was to write Orlando, a novel-cum-mock-biography in which the eponymous Orlando lives for centuries, during which time they transition from male to female.

The inspiration behind Orlando came from Vita Sackville-West, a fellow writer and Virginia’s friend and lover. Sackville-West came from an aristocratic family and grew up at Knole, a country house and former archbishop’s palace in Kent. As a woman, Sackville-West could not inherit the property, though she felt strongly attached to it throughout her life. By having Orlando transition from male to female, Woolf points out the ridiculous nature of outdated inheritance laws. At the same time, however, Woolf writes Knole into her novel and so gives Vita a literary version of her beloved childhood home. Both an intimate love letter to Vita Sackville-West and an important novel about gender fluidity and queer love, Orlando is at once whimsical, philosophical, and stylish.

6. The Waves, 1931

If Woolf felt the need for a break from writing “these serious poetic experimental books” before writing Orlando, it is interesting to note that the next novel she wrote was even more poetic and experimental than any she had written before.

The Waves centers around six friends: Bernard, Neville, Louis, Jinny, Susan, and Rhoda. Told via their interlinked consciousnesses, the reader follows them from childhood to adulthood and the individual struggles they face. Louis, for example, is the most intelligent of the group but is unable to attend university and feels out of place as an Australian in England, and Rhoda struggles with anxiety and her self-esteem. At the center is their mutual friend, Percival, who (crucially) never speaks. Throughout her work, Woolf explored human interiority, though nowhere does she explore it so thoroughly as in The Waves.

7. Between the Acts, 1941

Focusing on the lead-up to and performance of a pageant play as part of a festival in a small village in southern England shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, Between the Acts captures a moment of calm before the storm. Like Mrs Dalloway before it, the novel is set over a single day, on which the village’s annual pageant play is to be performed. While the pageant plays typically depict and celebrate English history, Miss La Trobe (the writer and artistic director of this year’s play) has subverted this format, and the play ends with a scene titled “Ourselves,” in which the players direct mirrors and other reflective objects at the audience. This, however, does not go down well with the audience, and Miss La Trobe feels the play has been a failure, though she is also hopeful for next year’s play…

Virginia Woolf, however, did not live to see the end of the war, and Between the Acts had to be published posthumously. Disappointed by the reception of her biography of Roger Fry and feeling unmoored and uncertain following the destruction of her London homes during the Blitz, she fell into a depression and suffered what was to be her final breakdown.

On March 28th, 1941, she waded into the River Ouse, with her pockets weighed down with stones, and drowned herself. She was 59 years old. She had suffered mental breakdowns throughout her life since her mother’s death, and she feared that she would not be able to survive another. Though her life was thus cut tragically short, she created a remarkable body of work – as the seven novels listed here attest.